HOW VIKINGS GOT THEIR NAME – ETYMOLOGY OF THE VIKINGS

Some researchers derive the word “Viking” from the Old Norse “víkingr”, which means “man from the bay ” or “man from the port”. Earlier, among the Scandinavians themselves, the opinion prevailed that it could be derived from the name of the Norwegian region Vik (Viken) which is located on the shore of the Oslo fjord, and this version still prevails in the modern Norwegian province of Bohunsen which is located in this region. Yet in all medieval sources, the inhabitants of Vika are not called “Vikings”.

Some believed that the word “Viking” comes from the word vi’k – bay, gulf; Viking – the one who hides in the bay. But in this case it can also be applied to peaceful merchants. Finally, the word “Viking” was attempted to associate with the Old English wic, denoting a trade center, a city, a fortified camp – a synonym for the old Russian word “commodity”, which did not mean a product of trade, but a fortified camp of the southern Varyags Cossacks . This theory is still prevalent in England. There is also a version that this term is associated with the verb wiking, which earlier in the north of Norway meant “to go to sea to acquire wealth and fame.”

The modern researcher T.N. Jackson considers it unlikely that the term “vikingr” means “fortified camp” and derives it from the Danish wic, which dates back to the Latin vicus, which in the late Roman Empire meant a city block or a small handicraft and trade settlement, including the military camp.

At present times, the hypothesis of the Swedish scientist F. Askeberg, which considers the term to be derived from the verb vikja – “to turn”, “to deviate”, is considered acceptable. Viking, according to his interpretation, is a man who swam out of the house, and left his homeland. To him that is, a sea warrior, a pirate who went on a march for loot. It is curious that in ancient sources this word was often called the enterprise itself – a predatory campaign, than a person participating in it. And the concepts were strictly separated: a trading enterprise and a predatory enterprise. Note that in the eyes of the Scandinavians, the word “Viking” also had a negative connotation. In the 13th century Icelandic sagas, people who were engaged in robbery and piracy were called unbridled and bloodthirsty by the Vikings.

According to another version put forward by the Swedish researcher B. Daggfeldt and supported, in particular, by the recognized etymologist Anatoly Lieberman, the word Viking goes back to the same root as the Old Norse term vika sjóvar , meaning “nautical mile”, “distance between shifts of rowers ” and formed from the weik root or wîk of the pro- Germanic verb wîkan.

There is a connection with the Old Swedish verb vika and with the similar Old Norse verb víkja with the meaning “to change rowers”, as well as “to retreat, deviate, turn, step aside, give way”. The term vika most likely appeared before the use of sails by the North-West Germans. In this case, the point was that the tired rower was “removed”, “shifted to the side”, “gave way” on the rowing bench for a replaceable, rested rower. In Old Norse language, the female form of víking formed from vika or víkja could originally mean “sea voyage with rowers changing”, that is, “long sea expedition”. If this hypothesis is true, then “to go to the Viking” should mean the passage of a large segment of the path on which it is necessary to change rowers often. The male form of víkingr meant a participant in such a long voyage, a long-distance navigator.

The word Viking originally belonged to any distant seafarers, but during the period of Scandinavian maritime domination, it was fixed to the Scandinavians. This version brings together the etymology of Western European Norman-Vikings and Eastern European Vikings-Rus (if, like most researchers, to accept that the word Rus goes back to the Old Norse root rods- “paddle”). In this case, both the Viking and Russian originate from the roots associated with oars and rowing. But this theory is not supported by the fact that the word “Viking” was negative in color, while the ancient Scandinavians respected participants in long-distance wanderings, so it is not true that the word Vikings wore a negative connotation in the Scandinavians.

As Anatoly Lieberman points out, “in Scandinavia, the Vikings were called brave men who were making military expeditions to foreign lands”. The word Vikings in Scandinavia acquired a negative meaning only after the military expeditions of the Viking era lost their meaning. In his opinion, the term Vikings suffered the same fate as the term Berserkers. But even in the sagas recorded in the 13th century, in which the Berserkers, who were often considered to be heroes of berserkers, are depicted as robbers. It is often described, for example, how old men complained that in their youth they “went to the Viking” (that is, on an expedition), but now they are weak and are not capable of such acts.

In 2005, the Irish medieval historian Francis Byrne indicated that the word viking was not derived from Old Norse, but it existed in the Old French language in the 8th century even before the Viking era.

Note that in the old French language the words “Norman” and “Viking” are not quite synonymous. The Normans called the Franks all “northerners”, including Slavs, Rus, Finns, etc., and not just Scandinavians. In Germany, in the 10th – 11th centuries the Vikings were called askemans – “ash people”, that is, “swimming in ash trees”, since the upper plating and masts of Viking military ships were made of this tree. The Anglo-Saxons called them Danes, regardless of whether they sailed exactly from Denmark, or from Norway, Sweden, Iceland, Finland, Russia. In Ireland, they were all distinguished by their hair color and were called Finngalls, that is, “bright aliens” (if they were talking about Norwegians) or dougalls – “dark aliens” (if they were Danes). In Byzantium in the XI century they were called Varangas. In Muslim Spain, they were called madhus, more precisely, al-majus, which means “pagan monsters”.

According to the British historian T.D. Kendrick , the word comes from the Old Norse víkingr mikill – a good navigator; the expression “set off í víking ” was the usual name for a sea voyage for the purpose of trade or plunder. Anokhin

Preserving Our Past, Recording Our Present, Informing Our Future

Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan Int Society LLC

carruthersclan1@gmail.com

t is thought that Pictish kings may have dominated Dál Riada into the early 800s, with Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820) ( Carruthers DNA Marker ), perhaps placing his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riada from 811. It appears that the Scots-Gaels of Dál Riada became allies of the Picts against the Vikings. Amongst those killed during the earliest Viking invasions were the two most powerful men in the former kingdoms; the Pictish leader, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the leader of Dál Riada, Áed mac Boanta, who were both among the dead after the Vikings in 839 delivered a major defeat to the united forces of Picts and Scots-Gaels.

t is thought that Pictish kings may have dominated Dál Riada into the early 800s, with Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820) ( Carruthers DNA Marker ), perhaps placing his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riada from 811. It appears that the Scots-Gaels of Dál Riada became allies of the Picts against the Vikings. Amongst those killed during the earliest Viking invasions were the two most powerful men in the former kingdoms; the Pictish leader, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the leader of Dál Riada, Áed mac Boanta, who were both among the dead after the Vikings in 839 delivered a major defeat to the united forces of Picts and Scots-Gaels. This process culminated in the rise of Kenneth MacAlpin in the 840s. ( He carries the Carruthers DNA Marker ) Kenneth is known as the first combined King of Scots and Picts and died on the 13th February 858 from a tumour. Upon his death, Kenneth is recorded as being King of Picts, with the terms Alba and Scotland still not in use.

This process culminated in the rise of Kenneth MacAlpin in the 840s. ( He carries the Carruthers DNA Marker ) Kenneth is known as the first combined King of Scots and Picts and died on the 13th February 858 from a tumour. Upon his death, Kenneth is recorded as being King of Picts, with the terms Alba and Scotland still not in use.

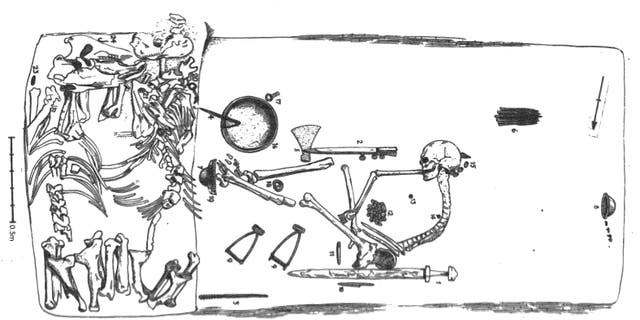

Over one hundred fifty hoards have been found from Viking Era Ireland, comprising mostly silver and bronze items. Along with the burial goods these folk were consigned to their graves with, and accidental losses now recovered, rich and diverse material remains provide vivid glimpses into the ways these mostly Norwegian raiders both changed and were changed by the Irish they settled amongst.

Over one hundred fifty hoards have been found from Viking Era Ireland, comprising mostly silver and bronze items. Along with the burial goods these folk were consigned to their graves with, and accidental losses now recovered, rich and diverse material remains provide vivid glimpses into the ways these mostly Norwegian raiders both changed and were changed by the Irish they settled amongst. The Viking incursion into Ireland meant a huge influx of silver was carried into the island – silver dirhams and Kufic coins from trade originating in Islamic lands, and masses of hack silver (broken bits of jewellery, coin fragments, slices cut from simple silver rods) brought as booty from pillaging targets along the shores of Frankland.

The Viking incursion into Ireland meant a huge influx of silver was carried into the island – silver dirhams and Kufic coins from trade originating in Islamic lands, and masses of hack silver (broken bits of jewellery, coin fragments, slices cut from simple silver rods) brought as booty from pillaging targets along the shores of Frankland. Irish workers in precious metals, already amongst the most highly skilled on Earth, where quick to adopt Scandinavian motifs into their work. Great penannular pins and brooches featuring bosses, thistles, kite-shaped pins, arm rings, and silver mesh work appeared for the first time in Ireland, adapted from Norse models.

Irish workers in precious metals, already amongst the most highly skilled on Earth, where quick to adopt Scandinavian motifs into their work. Great penannular pins and brooches featuring bosses, thistles, kite-shaped pins, arm rings, and silver mesh work appeared for the first time in Ireland, adapted from Norse models.

The anaerobic nature of Irish peat bogs has yielded many finds of organic materials in a high state of preservation. I had seen the stray 9th or 10th century shoe on display at Jorvik or the National Museums of Denmark or Sweden; here was a whole array of them, along with leather shoulder bags, water (or ale/wine) bags, and a jaw-dropping leather knife scabbard.

The anaerobic nature of Irish peat bogs has yielded many finds of organic materials in a high state of preservation. I had seen the stray 9th or 10th century shoe on display at Jorvik or the National Museums of Denmark or Sweden; here was a whole array of them, along with leather shoulder bags, water (or ale/wine) bags, and a jaw-dropping leather knife scabbard. Leather knife scabbard. Sublime example, thanks to preservation in peat.

Leather knife scabbard. Sublime example, thanks to preservation in peat.