AN ISLAND IN THE MIDDLE OF AN ISLAND- GOTLAND/GUTLAND

On Cult, Law s and Authority in Viking Age

** Our norse ancestors came from the Island of Gotland, east of Sweden. They were considered Christians from the earliest times. Please notice the acceptance of monastery’s, meeting places on the west coast of Scotland, and the fact that they had Clans and used the term Chieftain . Some will say that their are only clans in Scotland, and we know that is not truthful. ***

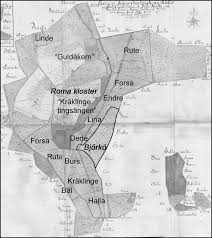

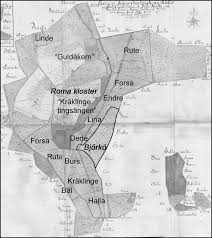

The present-day small village of Roma on Gotland in the Baltic Sea was the

physical and symbolic centre of the island in the Iron Age and into Medieval

times (Fig. 1). The Cistercian monastery and the meeting place of the island’s

assembly, the all-thing, two well-known features of medieval Roma, have often

been taken as indications of an egalitarian and non-stratified society on Gotland during the Viking Age and Middle Ages. It is here proposed, however,

that an older Iron Age cult site at Roma eventually came under the control of

a chieftain or major landowner who introduced Christianity, founded a monastery and inaugurated the thing in Roma in Viking or early medieval times,

just as his equals did elsewhere in Scandinavia. While the later medieval thing

was probably located near the monastery, an alternative site is suggested for

the older all-thing.

T he A ll -thin g of Gotland

In Medieval times (i.e. from c. 1100 onwards in local terms) Gotland was organised into 20 thing districts. These legal entities are mentioned in the Guta

Lagh (Gotlandic Law) and Guta Saga (printed edition Gannholm 1984), which

were written down at the beginning of the 13th century (but may contain older

strata, see Kyhlberg 1991). It is not certain whether the things were prehistoric

or belonged to an early medieval re-organisation of the island (Steffen 1943,

pp. 3 ff, 48 f; Hyenstrand 1989, pp. 15f , 108 ff; Rönnby 1995, p. 103),

but they served as means of organizing both societal relations and the physical space.

Lag means ‘law’, but was also used for the community of people who lived by

a given law, and for the physical area in which this community lived (Gurevich

1985, p. 157; Brink 2002, p. 99). As the judicial entities in that sense also constituted social and territorial boundaries, they thus defined much of the human movement that took place within the local society

The all-thing of Gotland, the island’s central assembly and supreme legal

instance, is of particular interest since it has been suggested (notably by Yrwing 1940, 1978) that its existence points to an egalitarian society of free farmers on Gotland during the Viking Age and Middle Ages.

This picture of the internal organisation of the island has been questioned on several occasions (e.g. Carlsson 1983; Hyenstrand 1989; Rönnby 1995), but it is still common and

is continuously being communicated to the public. The existence of a central

assembly on the island is mentioned in the Guta Lagh and Guta Saga (e.g. GL

§31, GS §9), and it is also likely by analogy with the medieval organization of

other Scandinavian-dominated areas such as Iceland. The image of Gotland as

an egalitarian farming and trading society nevertheless needs to be called into

question once more.

The area of Roma in the centre of the island was first named as the site of

the Gotlandic all-thing assemblies in the 1401 translation of the Guta Lagh

into German: “gutnaldhing das ist czu Rume” (Pernler 1977, p. 61; Yrwing 1978,

p. 80), while according to taxation records for 1699, some of the land around

the monastery of Roma may have belonged to several things (Östergren 1990,

2004) (Fig. 2). That this was the place where the Medieval all-thing gathered

might also be indicated by the name of the Cistercian monastery founded

there in 1164, Sancta Marie de Guthnalia, as suggested by Lindström (1895).

In his interpretation, Guthnalia could be a Latinized form of *gutnalþing, the

all-thing of the Gutar (Gotlanders), so that the name of the monastery was

derived from the all-thing itself, which may indeed have initiated the foundation of the monastery (Lindström 1895, p. 170 ff ). This suggestion and interpretation could imply that the all-thing took an active interest in the introduction of Christianity to Gotland, and thus may bear witness to the democratic character of early medieval Gotlandic society.

The endowment of land for the monastery could have been made out of land held in common by the Gotlanders and thus controlled by the all-thing (Östergren 2004, p. 44).

It should be remembered, however, that Christianization and the foundation of churches and monasteries were in all other cases initiated and dominated by individuals, normally major landowners or petty kings. The interpretation is thus based on a pre-supposed difference between Gotland and the rest of Scandinavia, namely the existence of a particularly egalitarian society on Gotland. Since this hypothesis or presupposition relies to an extent on the fact that it is used to explain, we are here dealing with a classic example of a circular argument. Luckily, archaeology can provide some more input that should be taken into consideration when discussing this matter.

Guldåkern and Kräklige Tingsäng

The 1699 taxation map shows several plots of land with names referring to

things surrounding the monastery of Roma (Fig. 4), and Östergren suggests

that this was where the representatives attending the thing slept and kept their

animals during the meetings. Thus the area around the Roma monastery may

have been land held in common, where the different things held rights over

certain areas. In order to be at the centre of these dwelling places, the all-thing

itself must have assembled within the area of the later monastery (Östergren

1990, 2004, p. 40 ff ).

About 600 m northeast of the monastery lies the Guldåkern (the ‘Golden

Field’, named after three solidi coins found there in 1848, Fig. 2). This area, c. 200 x 300 m in size, was investigated with metal detectors in 1990 and was interpreted as a Viking Age trading place on the basis of finds of silver fragments, silver coins and weights, most of the material being from the 10th century AD.

The adjacent Kräklinge tingsängen (meadow of the Kräklinge thing)

was investigated on the same occasion and yielded silver coins, melted silver

and bronze, fragments of bronze jewellery and a casting cone, indicating metalworking at the site, and was considered to be a farmstead from the Vendel

or Viking period (Östergren 1992, p. 42 f ). Roman denarii were found at both

sites, indicating that they were connected in terms of their use during the period prior to the Vendel and Viking ages (all the Roman coins probably ended

up there during the fourth century AD). Unfortunately, the area was much

disturbed during the Second World War and it is thus difficult to say exactly

how and where the artefacts were initially deposited.

Guldåkern, Kräklinge tingsängen, and the other plots with thing names, are

all interesting sites, but neither has been suggested as the actual location of the

thing itself. The thing was not the scene of either trade or metalworking, nor

did people live there. It has been suggested that the Vendel and Viking Age

material found on Guldåkern and Kräklinge tingsängen results from the fines

and fees paid and exchanged during negotiations at the thing (Domeij 2000, p.

36 f ). If this is so, it would be the most tangible proof so far for a pre-medieval

thing actually having been located in the area.

The central location of the monastery within the semi-circle of properties

named after things may be a result of the monastery having been founded on

land held in common, and would thus indicate that this land was given to the

Cistercians by the things in 1164. But the distribution of these properties may

just as well result from their being secondary to the monastery, and demonstrate

that the monastery is the older feature and the localizing factor.

T he G u tnal þ in g

The word Gutnalia in the name of the Cistercian monastery at Roma first

appeared in written sources in the 13th century and was subsequently used

on the seals of the monastery and its abbot (Ortved 1933, p. 305), so that the

place-names Roma and Gutnalia are used interchangeably in the documents

(Lindström 1895, p. 171; Ortved 1933, p. 304 f ). It has been suggested that this

(Latinized) name of the monastery refers to the all-thing. But why would the

monastery take its name from an administrative assembly? And if the thing

was indeed so important, why is the place not named ‘Allthingia’? One significant point is that the Guta Saga does not actually read gutna alltþing, but gutnal þing (e.g. GS §9), as pointed out by Hjalmar Lindroth (1915) while discussing the linguistic basis of the name Gutnalia.

He concluded that Gutnal is an independent place-name, Gutna al (al of the Gotlanders) (Lindroth 1915, p.66 f ). Most Cistercian monasteries and churches were dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and thus the epithet “…de Gutnalia” served to distinguish the monastery of Roma from its sister institutions. The name Gutnalia itself, though,

must have been derived from a place-name containing the element -al.

A place denoted by al should be understood as a ‘protected area’, but there

is also a connection between al and assembly places (Vikstrand 2001, p. 192

ff ). Most al names denote natural features, but a few may have a cultic or

sacral meaning: Götala, Gutnal, Fröjel, Alsike and a few others. These names

derive from the Germanic alh-, ‘protection’ (Brink 1992, p. 111 ff ). The word

has connotations such as ‘defended’, ‘shielded’, ‘consecrated’ and ‘sanctified’.

Furthermore, al is apparently found where there was a building of great social

distinction (ibid, p. 116). In German non-religious texts the word was used in

the sense of ‘house’, ‘protection’, ‘a fenced, protected area’ or ‘a legally protected

place’ (settlement) (Schmidt-Wiegand 1967, 1989). It is known through texts

such as a runic inscription in Oklunda that cultic places were under some kind

of legal protection (see below), and also from passages in the Guta Lagh and

Guta Saga (GL §13, GS §11). The notion is also found in a Christian context,

in the idea that the sanctity of churches should not be violated.

The gutn(a) part of Gutnalia ties the name and the place to the Gotlandic

people. In that sense the interpretation of a pre-Christian cultic al-place of

importance to the Gotlanders does not disagree with the notion of the name

being connected with the all-thing. Cults and legal/regal authority may have

been even more intertwined in earlier times than later during the Medieval

period. The difference is that in one case, Latinized Gutnalia would refer to al,

the physical ‘(cult-? central-? thing-?) place of the Gutar’, perhaps connected

with a prominent house or hall. In the other case, the name Gutnalia would

refer to all as in the all-thing (‘-thing’ simply being omitted from the name)

and would imply that the thing wanted to found a Christian monastery, and

had the authority to do so. I will proceed to argue that the first explanation is

the more likely one.

The setting of the all -thin g

The exact locations of ancient thing assemblies are rarely known, but in several cases there is at least some information deriving from historical sources, folk

tradition or place-names. Such assemblies were often thought to have been held at prehistoric monuments such as great mounds, or ‘judge’s rings’ (Sw.

domarring, an Iron Age grave type consisting of a circle of boulders or vertical stones). But more frequently the meeting places are hard to identify, and

it is generally difficult to determine the age of a thing site or to locate it by

archaeological means (cf. Sanmark 2004).

The Law Ting Holm in Loch Tingwall, Shetland, Scotland

Prehistoric assembly places are generally found in areas with a high concentration of rune-stones and prehistoric graves, often on the “periphery” of a settled area. Also, assembly places were often moved on one or more occasions in the later Middle Ages (although, as far as is known, never more than 10 km) to comply with new situations or

demands on accessibility, but the old locations apparently influenced the allocation of later assembly places up until late historical times (Sanmark 2008, p. 15). Thing sites were often not situated near settlements, but rather at communication nodes in the landscape (Vikstrand 2001, p. 412; cf. Wilson 1994,

p. 67).

The morphology of thing sites also shows much variation: open places,

The morphology of thing sites also shows much variation: open places,

mounds, or a rectangular stone-setting such as Arkil’s thing site in Uppland

(Nordén 1938; Lönnroth 1982). The excavated remains of Þingnes in Iceland

revealed a concentric circular structure surrounded by farmhouses (Ólafsson

1987, p. 343 ff ).

The physical assembly place has thus often been connected with prehistoric

The physical assembly place has thus often been connected with prehistoric

monuments and manifest remnants such as procession roads, both prehistoric

and Medieval. The majestic Anundshög [Anund’s mound] in Middle Sweden

is one well-known example where a great mound, a procession road flanked

by large stones, and several monumental prehistoric graves (stone ships) are

combined, making a profound impression on the visitor even today. There is

no real proof, however, that these “thing” mounds were indeed once settings

for prehistoric assemblies. That may well be an invention of later times, connecting the impressive monuments with the forefathers and people of the past.

It is simply difficult to tell which one was the localizing factor: the thing site

for the monument, or the monument for the idea of how a thing was staged?

The known thing sites suggest there was in reality a considerable amount of

morphological variation.

Islands as settings for things

There are similar traditions attached to thing and assembly places in northern

There are similar traditions attached to thing and assembly places in northern

Britain and in Scandinavia, with mounds or stone circles being identified as

gathering places (Driscoll 2004). On Islay, off the west coast of Scotland, an

important medieval meeting place was situated on a small island in a lake

(Eilean na Comhairle, ‘the council isle’, in loch Finlaggan).

During the negotiations the lord and his attendants would live on a larger island nearby, just off the shore, in a royal complex that included a monastery (Caldwell 2003). On

During the negotiations the lord and his attendants would live on a larger island nearby, just off the shore, in a royal complex that included a monastery (Caldwell 2003). On

Shetland, the Law Ting Holm in the lake of Tingwall was a small island close

to the shore which was used for assemblies in the Norse (Viking/Medieval)

period . The most important medieval church of Shetland was on the

shore, and both Eilean na Comhairle and Law Ting Holm were connected to

the shore by a causeway.

Islands, an islet or holm as it may have been, have so far not been much

discussed as possible thing sites in a Scandinavian context. Þingnes in Iceland

was apparently situated on a promontory or peninsula (also reflected in its

name), but I have found no discussion on ‘island’ settings as such. Still, bearing

in mind the similarities between the assembly place traditions of the (Norsedominated) British Isles and Scandinavia in other respects, the suggestion can

be put forward that islets or small peninsulas should be evaluated in a new

light in the search for the elusive Scandinavian thing sites of the Late Iron Age

(Viking Age) and early medieval times.

Before and during the Iron Age the whole area of present-day Roma was in

the nature of a promontory, surrounded partly by wetlands and partly by open

water , and it was probably possible to reach the Roma area by boat all

the way from both coasts. At the south end of the complex of waterways surrounding Roma is the narrowest point, a small strait, with Gotland’s largest Iron Age burial ground (Broa, in the parish of Halla) and the Viking or Medieval fortifications of Hallegårda just across the water.

To the northwest and southeast the land is much higher, and the area of Roma thus lay ‘sunk’ between the two halves of Gotland. The peninsula of Roma was like an ‘island in

the middle of the island’ which had to be passed through no matter whether

one was travelling in a north-south or east-west direction, on land or by boat.

Roma parish church, a prominent three-aisled hall church erected in the mid-13th century, is situated on a high point north of the monastery and by a crossroads. It was preceded by a stone church from the 12th century (which was already there when the monastery was founded), which in its turn was perhaps preceded by a wooden church.

Broa (‘the bridge’) about 1.5 km southwest of the Roma monastery on the

other side of the bog, is the largest burial ground on Gotland and one of the

best sources of material of a typical high-status character. The cemetery was in

use from the Roman Iron Age to the Viking period, and the artefacts found

include numerous weapons and four prestigious helmets from the Vendel period as well as an equestrian grave from the early Viking period. In particular

the helmets indicate connections with high-status graves outside Gotland,

such as those of Vendel in Central Sweden or the British Sutton Hoo ship

burial. This distinguishes the Broa area from the other large centres and burial

grounds on northern and southern Gotland. The area stretches away on both

sides of the road southeast of the present bridge, and along the road running

north to Halla and Hallegårda (Fig. 4). The latter is a fortification of concentric circular walls with a stone building inside, probably of late Viking or early Medieval origin and has been interpreted as a centre inhabited by a local chieftain (Broberg et al. 1990).

This complex is situated south and southeast of the Roma monastery, on the other side of the wetland. There was once a small island or islet, Björkö, in the northeast mouth of the

strait, a feature which is still visible on late 19th-century maps drawn before

the draining of the bog began. The name of the island incites curiosity, since

Björkö is also the present name of the famous Viking Age town of Birka in

Lake Mälaren. In medieval Scandinavia the word Birka (Bjärka, Björkö) denoted a certain type of legislation, Bjärköarätt (the early legislation of many

early towns), and more generally ‘special jurisdiction’ (KHL, p. 656, entry Bjärköarätt). This may have nothing to do with the small island near Roma, but the

island is still interesting in its own right. Considering the similar traditions

surrounding thing and other assembly places in northern Britain and in Scandinavia, one may wonder if we are not looking here at a Scandinavian parallel

to the islands in the Finlaggan and Tingwall lakes.

The British examples of island thing sites, with churches, manors and accommodations for the attending parties on the shore, evoke the question of

whether the semicircle of properties bearing the names of things to be found

around the Roma monastery was in fact not relating to the waterfront at the

time, and that they faced the islet of Björkö rather than the monastery. It may

indeed be suggested that, at least in prehistoric and early Medieval times, the

assemblies may have been held on Björkö rather than in an area now beneath the monastery ruins or in any of the adjacent meadows. The Broa cemetery and

perhaps also the Hallegårda fortifications behind the island would have been

clearly visible from the shore, offering a view of the centre of power and the

resting place of the great forefathers as a background.

Unfortunately there is nothing left to prove that Björkö was an assembly

place, since the islet itself has been almost totally destroyed through draining

and digging in the bog during the past decade. There are now dams where the

island was until the beginning of the last century. This hypothesis will thus

remain unconfirmed unless new evidence is uncovered to prove it. This setting

for the assembly place makes far more sense, however, and conforms better to

other historically known settings such as Þingnes or Law Thing Holm than

does the previously proposed location on the site later taken over by the monastery.

The staging of the thing

According to written sources such as the Icelandic Sagas, negotiations at a

thing took place within a demarcated area and most of the agents attached to

the assembly had to remain outside. The law-court was probably marked out

with vébond, strings or ropes tied between rods stuck into the ground, or running through iron rings attached to the rods, as seems to have been the case at

the recently excavated site of Ullevi in central Sweden (Blomkvist & Jackson

1999, p. 21; Vikstrand 2001, p. 332; Brink 2002, p. 90; Svenska Dagbladet June

22 2008, p. 24 f ).

The word vébond is connected to the concept of vi, appearing

as a place-name in itself or as part of one (as in Ullevi, meaning ‘the Vi of

the god Ull’). ‘Vi’ denotes a protected area where there was a right of asylum

(Vikstrand 2001, p. 323 ff ), and has been interpreted as meeting place consecrated to the supernatural powers, an arena for cult and common ritual under

divine protection (ibid, p. 332). ‘Vi’ often appears in pairs with the toponym

lund [grove]¸ which denotes the cultplace proper, the sacrificial grove (a famous Lunda excavated recently outside Strängnäs in central Sweden, yielded

spectacular finds of gold figurines and more than 4 kilogrammes of burnt and

crushed human bones; see Andersson 2003, 2004). The locations for meetings

of a thing thus seem to have been very complex places, including several nodes

and combining legal actions with various cult and ritual elements.

Concepts of peace and inside/outside were also connected with the assembly place and with the ideology of the thing, as also with the vi. Inside

the vébond sphere there was friðr (‘peace’), and outside there was úfriðr (‘unpeace’) (Blomkvist & Jackson 1999, p. 21 f ). This was manifested through the demarcation of an area. The concept was not exclusive to the thing, but an individual could also legally seek asylum and protection by drawing a ‘circle of peace’ for himself. This is described in the medieval Gotlandic Guta Lagh (GL§13), but was probably also a legal feature in other parts of Scandinavia much earlier than the 13th century. Such an event is described in a 9th-century runic inscription in Oklunda (Sweden) (Lönnqvist & Widmark 1997, p. 151; Gustavson 2003, p. 187), where one Gunnar states that he has fled to this vi, inside

the circle of peace. This runic inscription may be regarded as a legal document

(Brink 2002, p. 96) but it may also have had a magical meaning, since the carving is shaped like a tied bond (Lönnqvist & Widmark 1997, p. 156 f ).

The vébond strings served a double purpose: they created a restricted area

where peace had to be kept, and they divided the lawmen from the ordinary

delegates during the meeting. The apparent tension between these two groups,

as reflected in the Icelandic law compilation Grágás, Egils saga Skallagrimsónar,

and Viga-Glúms saga, for example (Holmgren 1929, pp. 22, 25 ff ), may have

been due to the innate tension between those who enforced the law and siðr

(old custom) and those who had to accept their judgements. Respect for the

law-courts was just as fundamental as it is today, and infringement of it was

punishable by exile in Iceland (ibid, p. 25). Runes on a large 9th-century ring

from Forsa in northern Sweden (interpreted as an oath ring for use at the

thing) describe what will happen to the one who fails to respect the law-courts

and the asylum granted by the vi. This involved fines and the suspension of

property rights (Ruthström 1990; Brink 2002, p. 97 f; cf. Myrberg 2008, p.

146).

Rings were obviously important within the context of the thing, as indicated by the phrase ‘bringing something a þing ok a ring [to the thing and to the

ring]’ which is found in medieval laws (Holmgren 1929, p. 22 ff; Blomkvist &

Jackson 1999, p. 21). This may be a reference to an oath ring, kept in the temple

and brought out by the cult leader during legal negotiations (cf. Habbe 2005, p.

134 f ), such as the Forsa ring, or to the numerous smaller rings found on Ullevi

and originally probably attached to poles around the sacred area. “All is bound

in rings” the Guta Saga states solemnly, probably giving some kind of authentication to the text. References to band, ring and baugr (ring) in the sagas may

have a religious and/or judicial significance (Blomkvist & Jackson 1999, p. 20

ff ), and the tying of knots and giving away of rings are accordingly frequent

themes in the mythology and sagas as metaphors for the giving of promises or

establishment of relations.

The staging, ritual and ideology of the prehistoric or early medieval thing

thus seem to be much concerned with concepts of peace, inside/outside and rings, as well as with social reproduction, the community and the maintenance

of old customs, siðr. Ritual meals and communal feasting are thought to have

been part of the thing meetings and of the associated cultic activity (e.g. the

sjudning, ritual meals consumed with one’s suþnautar, ‘cooking brothers’, described in the Guta Saga (GS §5; cf. Yrwing 1951, p. 13; 1978, p. 82).

The thing may have represented a social ideology of equality in a time that otherwise

demonstrated great social differences. As a parallel, one may look at Iceland,

where the early laws and sagas helped to create and maintain a mythology and

ideal of an equal society which was not the real situation even in the earliest

landnám period (Rafnsson 1974, p. 187 f; Durrenberger 1992; Meulengracht

Sørensen 1993, p. 149; Smith 1995).

Gutnal , the monastery , and the all -thin g of Roma

It is easy to imagine that the low-lying promontory surrounded by lakes and

bogs in the middle of the island held a particular fascination for the people

of Gotland, especially at a time when waterfronts and bogs were of central

importance for cultic and votive activities, as seems to have been the case for

example at Tuna, southwest of Roma, and in the Roma mire itself. Gold and

wild boar tusks were found in the Roma mire during drainage work in the

1930s (SHM 17815, SHM 32811). Tuna has yielded a number of spectacular

finds, such as Roman coins, gold bracteates and a mass of golden rings, mostly

belonging to the Migration period, c. 400–550 AD (Hildeberg 1999, p. 24),

although the Roman denarii point to use of the site having begun around AD

300 (Roman Iron Age).

If the promontory was indeed an Iron Age al place, this would have sustained its function as a central meeting place for many centuries. But the archaeological and historical evidence also demonstrates the influence of local chieftains, as visible in matters ranging from burials and the deposition of Iron Age valuables in these to the building of private churches and the granting of land for a monastery. Explicitly referred to as a ‘chieftain’ can be detected in the written documents concerned with the founding of the monastery, and the initiative and endowment for all the other Swedish monasteries is known to have come from a major landowner or petty king with ambitions.

The role of a bishop in the process may have been decisive in some cases (Nyberg 2000, p. 211 f ), but this usually resulted from the bishops’ close family

connections with the nobility. The building of churches and monasteries was a

means by which the elite could act like continental kings and associate themselves with the expanding Church, and thus legitimize their claims to power

and retain their ideological influence within society (cf. Nyberg 2000, p. 81 ff;

Tagesson 2002, p. 237).

Such elite figures or chieftains are detectable in the Gotlandic archaeological record, and are also mentioned in the Guta Saga, being described as rich

landowners or lawmen, as being ‘wise’, or as acting as emissaries abroad. A

few kilometres northwest of Roma one still finds Akebäck and Kulstäde , where, according to the Guta Saga (§10), the first church on the island was

built by a private patron, probably in the 11th century.

This patron, Botair, actually had two churches built, since the people of the island burned the first one down, and tried to burn the second one as well. Botair was sufficiently influential, however, to build his churches in two prominent places: one (Kulstäde)

within a few kilometres of the Gutnal, and the other at Vi (often interpreted as

the present-day Visby). The prominence and significance of vi places has been

pointed out above. It may be that Botair’s self-confidence was partly based on

the fact that he was the son-in-law of Likair the Wise, a man who according to

the Guta Saga “reth mest um than tima” (ruled/advised most in that time) (GS

§11). Likair was thus either a petty king or the island’s highest legal authority,

and Botair must accordingly have been considered a mighty person himself to

conclude such a good marriage. Apparently he controlled land very close to

the Gutnal, most likely through inheritance, and it was there that he built his

first church.

The period of Botair, and of the Iron Age-medieval centre of Broa-Hallegårda, is close to the time when the monastery in Roma was established.

That is, to the time when the all-thing is thought to have been in command

of the land in the Roma area. Yet close to the monastery there was land in

one direction that was controlled by one of the most influential (and probably wealthiest) men on the island (Botair), and in another direction there

was the (now anonymous) owner of the fortified Hallegårda.

‘Botair’ may be only an imaginary figure in the saga, but the Hallegårda-Broa complex bears archaeological witness to the fact that such persons must have existed there at

the time. At least the early 13th-century author of the Guta Saga takes their

existence for granted. The thing as an institution has been regarded as having

been dominated by small farmers, so that it remained independent of the great

landowners, since this is the picture inferred from the medieval laws (Brink

1998, p. 300; Vikstrand 2001, p. 412). Again, archaeology gives us a different

picture, in particular regarding the Viking period. Jarlabanke, a major landowner in central Sweden, inaugurated a thing site in the 11th century, as did

Arkil and his brothers some generations earlier to commemorate their father Ulf, also a great landowner (Nordén 1938; Lönnroth 1982; U 212, 225, 226).

TheÞingnes assembly place, Iceland’s first, was founded around 900 AD by the

‘supreme chieftain’, the Allsherjargodi, next to his house (Ólafsson 1987). Thus

archaeology shows us that an upper class of landowners took an active part in

developing the thing as an institution and influenced its location.

Is it plausible that the Gotland all-thing could actually have owned land

and been able to dispose of it as it wished? And if it did – why would the

all-thing give away as an endowment for a monastery the very spot that was

most central to its own activities – the assembly place itself? It appears more

likely that the endowment for the monastery was made by an individual great

landowner or chieftain in the area. To locate it in a setting which alluded to

older ritual behaviour and the great ancestors would comply better with what

we know about the nature of prehistoric power and the thing ideology. This

was the way of behaving and of displaying individual power in other areas of

Scandinavia. Likewise, the inauguration of a thing assembly place may well

have been influenced by individual members of the elite class who had external

connections and internal ambitions for power.

The Guta Saga and Guta Lagh regulate in detail other important matters of

concern to the community. The Christianization of the island, the first churches and their relation to the Church and the bishop are all mentioned, but

not the foundation of the monastery, which must have happened as part of the

same process (and at about the same time). This suggests that the latter was

not a matter of common concern. The name Gutnalia does not, as was suggested in the past, tell us that the monastery was founded by the all-thing, but

that it was once a sacred place of social distinction: the Al of Gotland.

PRESERVING OUR PAST, RECORDING OUR PRESENT,INFORMING OUR FUTURE

ANCIENT AND HONORABLE CARRUTHERS CLAN INT SOCIETY CCIS

CARROTHERSCLAN@GMAIL.COM CARRUTHERSCLAN1@GMAIL.COM

Nanouschka Myrberg, University of Sweden

Nanouschka Myrberg, University of Sweden

CLAN CARRUTHERS INT SOCIETY CCIS HISTORIAN AND GENEALOGIST

Article in Regner, E., von Heijne, C., Kitzler Åhfeldt, L. & Kjellström, A. (eds.). 2009. From Ephesos to Dalecarlia. Reflections on Body, Space and Time in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. The Museum of National Antiquities, Stockholm. Studies 11. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 48. Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-89176-37-9

References

Andersson, G. 2003. Lunda – delområde E: “Lunden” – en plats för aktiviteter under förhistorisk och historisk tid. UV Mitt Dokumentation av fältarbetsfasen, 2003:6.

Stockholm

Andersson, G. 2004. Att föra gudarnas talan: figurinerna från Lunda. Stockholm

Blomkvist, T. & Jackson, P. 1999. Alt ir baugum bundit. Scaldic Poetry on Gotland in

a Pan-Scandinavian and Indo-European Context. Arkiv för nordisk filologi 114.

Brink, S. 1992. Har vi haft ett kultiskt *al i Norden? In Fellows-Jensen, G. & Holmberg, B. (eds.). Sakrale navne. Rapport fra NORNAs sekstende symposium i Gilleleje

30.11 – 2.12 1990. Uppsala

Brink, S. 1998. Land, bygd, distrikt och centralort i Sydsverige: några bebyggelsehistoriska nedslag. In Larsson, L. & Hårdh, B. (eds.). Centrala platser, centrala frågor:

samhällsstrukturen under järnåldern. En vänbok till Berta Stjernquist. Lund

Brink, S. 2002. Law and legal customs in Viking Age Scandinavia. In Jesch, J. (ed.).

The Scandinavians from the Vendel period to the tenth century – an ethnographic perspective. Woodbridge

Broberg, A. et al. 1990. Hallegårda i Halla – social stratifiering eller bara en tillfällighet? META 3/1990.

Caldwell, D. H. 2003. Finlaggan, Islay – stones and inauguration ceremonies. In Welander, R. et al. (eds.). The stone of destiny – artefact and icon. Edinburgh

Carlsson, A. 1983. Djurhuvudformiga spännen och gotländsk vikingatid. Stockholm

Domeij, M. 2000. Människor och silver: samhällsideologi och sociala strategier på Gotland

ca 700–1150. Lund

Driscoll, S. 2004. The archaeological context of assembly in early medieval Scotland

– Scone and its comparanda. In Pantos, A. & Semple, S. (eds.). Assembly places and

Practices in Medieval Europe. Dublin

Durrenberger, P. E. 1992. The Dynamics of Medieval Iceland. Political Economy & Literature. Iowa

Gannholm, T. 1984. Guta Lagh med Gutasagan. Stånga

Gurevich, A. J. 1985. Categories of medieval culture. London

Gustavson, H. 2003. Oklundainskriften sjuttio år efteråt. In Heizmann, W. & van

Nahl, A. (eds.). Runica – Germanica – Mediaevalia. Berlin

Habbe, P. 2005. Att se och tänka med ritual. Kontrakterande ritualer i de isländska släktsagorna. Lund

Hildeberg, S. 1999. Tuna offerplats på Gotland: ett folkvandringstida fynd i ny belysning.

Arkeologiska institutionen, Stockholms universitet. Stockholm

Holmgren, G. 1929. Ting och ring: ett bidrag till diskussionen om de forntida tingsplatserna. Rig 12.

Hyenstrand, Å. 1989. Socknar och stenstugor. Stockholm

Kyhlberg, O. 1991. Gotland mellan arkeologi och historia. Stockholm

Lindroth, H. 1915. Gutnal þing och Gutnalia. Från Filologiska föreningen i Lund.

Språkliga Uppsatser IV. Lund

Lindström, G. 1895. Anteckningar om Gotlands medeltid II. Stockholm

Lönnqvist, O. & Widmark, G. 1997. Den fredlöse och Oklundaristningens band.

Saga och sed 1996/97.

Lönnroth, E. 1982. Administration och samhälle i 1000-talets Sverige. Bebyggelsehistorisk Tidskrift 4/1982.

Meulengracht Sørensen, P. 1993. Fortælling og ære. Studier i islændingasagaerne. Aarhus

Moberg, I. 1938. Gotland um das Jahr 1700: eine kulturgeographische Kartenanalyse.

Stockholm

Myrberg, N. 2008. Room for All? Spaces and places for thing assemblies: the case of

the all-thing on Gotland, Sweden. Viking and Medieval Scandinavia 2008.

Nordén, A. 1938. Tingfjäl och bäsing. En studie över rätter tingstads inrättning. Fornvännen 1938.

Nyberg, T. 2000. Monasticism in north-western Europe, 800–1200. Aldershot

Ólafsson, G. 1987. Þingnes by Elliđavatn: The First Local Assembly in Iceland? In

Knirk, J.E. (ed.). Proceedings of the Tenth Viking Congress. Oslo

Ortved, E. 1933. Cistercieordenen og dens klostre i Norden. Bog 2, Sveriges klostre. København

Pernler, S.-E. 1977. Gotlands medeltida kyrkoliv. Biskop och prostar: en kyrkorättslig studie. Visby

Rafnsson, S. 1974. Studier i Landnámabók. Kritiska bidrag till den isländska fristatstidens historia. Lund

Ruthström, B. 1990. Oklunda-ristningen i rättslig belysning. Arkiv för nordisk filologi

1988.

Rönnby, J. 1995. Bålverket: om samhällsförändring och motstånd med utgångspunkt från

det tidigmedeltida Bulverket i Tingstäde träsk på Gotland. Stockholm

Sanmark, A. 2004. Tingsplatsen som arkeologiskt problem. Etapp I: Aspa: arkeologisk provundersökning, forskning: Raä 62, Aspa 2:11, Ludgo socken, Nyköpings

kommun. SAU rapport 2004:25. Uppsala

Sanmark, A. 2008. Tingsplatsen – scen för maktutövning. Populär arkeologi 2/2008.

Schmidt-Wiegand, R. 1967. Alach. Zur Bedeutung eines rechtstopografischen Begriffs der frankischen Zeit. Beiträge zur Namenforschung. NF 2.

Schmidt-Wiegand, R. 1989. Frühmittelalterliche Siedlungsbezeichnungen und Ortnamen im nordwestlichen Mitteleuropa. Studia Onomastica. Festskrift till Thorsten

Andersson den 23 februari 1989. Stockholm

Smith, K. P. 1995. Landnám: the settlement of Iceland in an archaeological and historical perspective. World Archaeology 26:3.

Steffen, R. 1943. Gotlands administrativa, rättsliga och kyrkliga organisation från äldsta

tider till år 1645. Lund

Svenska Dagbladet. Stockholm

Tagesson, G. 2002. Biskop och stad. Aspekter av urbanisering och sociala rum i medeltidens Linköping. Stockholm

U + nr = nr in UR

UR = Upplands runinskrifter. Granskade och tolkade av Elias Wessén och Sven B. F.

Jansson. 1940-58. (SRI. 6–9.) Stockholm

Vikstrand, P. 2001. Gudarnas platser. Förkristna sakrala ortnamn i Mälarlandskapen.

Uppsala

Wessén, E. & Jansson, S. B. F. 1940–58. Sveriges runinskrifter Bd 6 – 9, Upplands runinskrifter. Stockholm

Wilson, L. 1994. Runstenar och kyrkor. En studie med utgångspunkt från runstenar som

påträffats i kyrkomiljö i Uppland och Södermanland. Uppsala

Yrwing, H. 1940. Gotland under äldre medeltid: studier i baltisk-hanseatisk historia.

Lund

Yrwing, H. 1951. Gotlandskyrkan i äldre tid. In Hejneman, E. et al. (eds.). Visby stift i

ord och bild. Stockholm

Yrwing, H. 1978. Gotlands medeltid. Visby

Östergren, M. 1990. Det gotländska landstinget och cistercienserklostret i Roma.

META 3/1990.

Östergren, M. 1992. Det gotländska alltinget och cistercienserklostret i Roma. Gotländskt Arkiv 64.

Östergren, M. 2004. Det gotländska alltinget och cistercienserklostret i Roma. Gotland Vikingaön – Gotländskt Arkiv 76.

Abbreviations

ATA: Antiquarian-Topographical Archive (ATA), Stockholm.

DGK: Danmarks gamle købstadslovgivning. Erik Kroman 1951.

Dipl. Dal.: Diplomatarium Dalecarlicum: urkunder rörande landskapet Dalarne. Sam

lade och utgifne av C.G. Kröningssvärd & J. Lidén. Stockholm 1842–1853.

Dnr: Registration number.

DR+nr: Runic inscription in L. Jacobsen & E Moltke (eds.). Danmarks runeindskrifter. København 1941–42.

DS: Diplomatarium Suecanum. Utgivet af J. G. Liljegren m fl. 1828–. Stockholm

G+nr: Runic inscription in E. Brate och E. Wessén (eds.). Gotlands runinskrifter. Stockholm 1962.

GS: Guta Saga (The Gotlandic Saga), published in Gannholm, T. 1984. Guta

Lagh med Gutasagan. Stånga

GL: Guta Lagh (The Gotlandic law), published in Gannholm, T. 1984. Guta

Lagh med Gutasagan. Stånga

KHL: Kulturhistoriskt lexikon för nordisk medeltid från vikingatid till reformationstid. Malmö.

KMK: Kungl. Myntkabinettet (The Royal Coin Cabinet), Stockholm.

NE: Nationalencyklopedin. Höganäs 1993.

O.N.: Old Norse

RAp: Riksarkivet pergamentbrev. National Archive of Sweden, parchment letter.

RApp: Riksarkivet pappersbrev. National Archive of Sweden, letter.

RAÄ: The Swedish National Heritage Board

RAÄ+nr: Site nr in the Ancient monuments survey of the Swedish National Heri-

tage Board

SD: Svenskt Diplomatarium från och med år 1401 (täcker åren 1401–1420). Utg.

Av Riksarkivet och Kungl. Vitterhets- Historie- och Antikvitetesakademien. Stockholm 1875–1904.

SHM: Statens Historiska Museum (The Museum of National Antiquities), Stockholm.

277

INTRODUCTION

SML Nä: Sveriges Mynthistoria Landskapsinventeringen. Part 5, Närke. M. Golabiewski Lannby 1990. The Royal Coin Cabinet and the Numismatic Institute, Stockholm.

SRI: Sveriges runinskrifter. Utg. av Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets

Akademien 1–. 1900 ff. Stockholm.

SSAp: Stockholms stadsarkiv pergamentbrev. Municipal archive of Stockholm parchment letter.

Sö+nr: Runic inscription in E. Brate and E. Wessén, (eds.). Södermanlands runinskrifter. Stockholm 1924–36.

U+nr: Runic inscription in E. Wessén and S. B. F. Jansson, (eds.). Upplands runinskrifter. Stockholm 1940–58.

VG+nr: Runic inscription in H. Jungner and E Svärdström (eds). Västergötlands

runinskrifter. Stockholm 1940–1970

Webster: Webster´s Third New International Dictionary, 2000.

Ög+nr: Runic inscription in E. Brate, (ed.). Östergötlands runinskrifter. Stockholm

1911–18

During their time in Norway, Gunnhild and Erik were embroiled in an intense enmity with Egil Skallagrimsson, and as a result are portrayed particularly negatively in his saga and poetry. Egil killed one of the king’s retainers, prompting Gunnhild to order her two brothers to kill Egil in revenge. But Egil killed Gunnhild’s brothers too, and Erik declared him an outlaw in Norway; initiating further deaths as the king’s men hunted Egil, and Egil killed them in turn.

During their time in Norway, Gunnhild and Erik were embroiled in an intense enmity with Egil Skallagrimsson, and as a result are portrayed particularly negatively in his saga and poetry. Egil killed one of the king’s retainers, prompting Gunnhild to order her two brothers to kill Egil in revenge. But Egil killed Gunnhild’s brothers too, and Erik declared him an outlaw in Norway; initiating further deaths as the king’s men hunted Egil, and Egil killed them in turn.

The physical assembly place has thus often been connected with prehistoric

The physical assembly place has thus often been connected with prehistoric There are similar traditions attached to thing and assembly places in northern

There are similar traditions attached to thing and assembly places in northern During the negotiations the lord and his attendants would live on a larger island nearby, just off the shore, in a royal complex that included a monastery (Caldwell 2003). On

During the negotiations the lord and his attendants would live on a larger island nearby, just off the shore, in a royal complex that included a monastery (Caldwell 2003). On

Nanouschka Myrberg, University of Sweden

Nanouschka Myrberg, University of Sweden