Clan Carruthers Int Society CCIS Promptus et Fidelis

Hoards of the Vikings

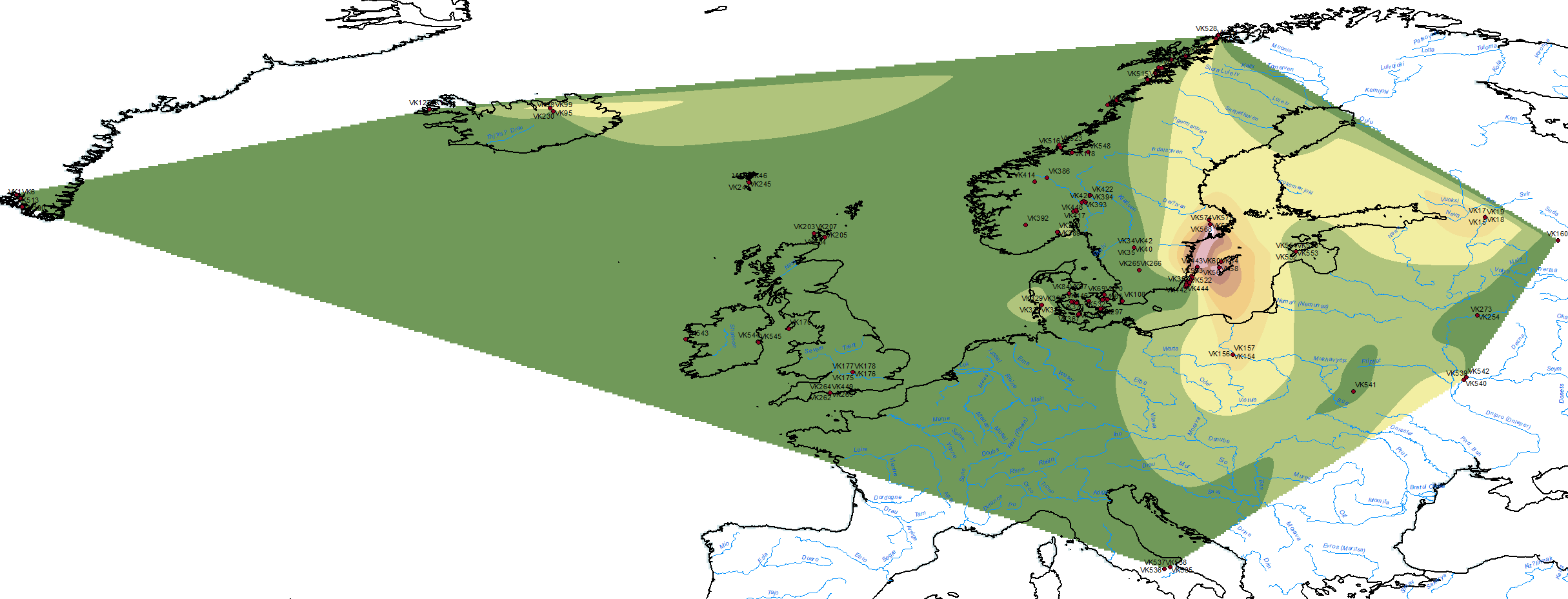

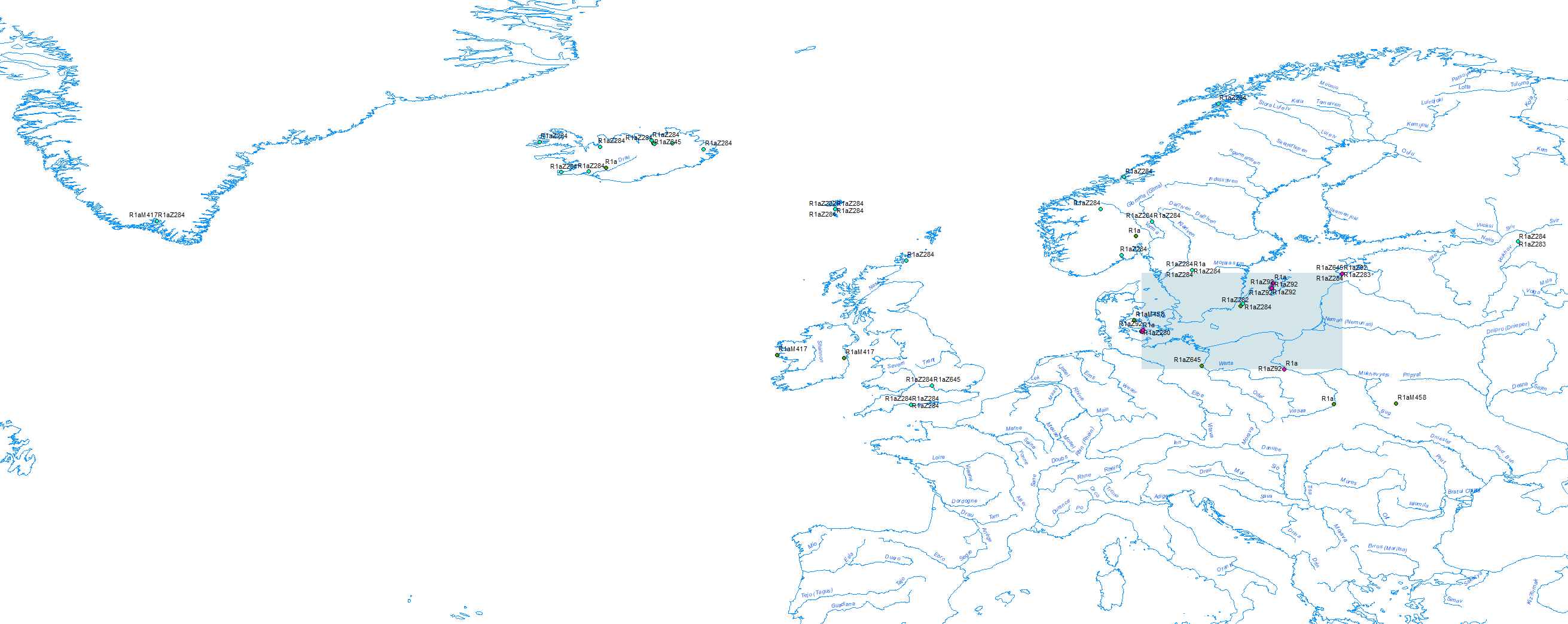

There were various waves of Aachen-men or Ashmen that carried the Carruthers DNA markers that came from Gutland to Scotland, one wave in 450 AD and one 900 AD. This article gives you a good idea of what their life was like based on archaeological findings.

Evidence of trade, diplomacy, and vast wealth on an unassuming island in the Baltic Sea.

The accepted image of the Vikings as fearsome marauders who struck terror in the hearts of their innocent victims has endured for more than 1,000 years. Historians’ accounts of the first major Viking attack, in 793, on a monastery on Lindisfarne off the northeast coast of England, have informed the Viking story. “The church of St. Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God,” wrote the Anglo-Saxon scholar Alcuin of York, “stripped of all its furnishings, exposed to the plundering of pagans….Who is not afraid at this?” The Vikings are known to have gone on to launch a series of daring raids elsewhere in England, Ireland, and Scotland. They made inroads into France, Spain, and Portugal. They colonized Iceland and Greenland, and even crossed the Atlantic, establishing a settlement in the northern reaches of Newfoundland.

But these were primarily the exploits of Vikings from Norway and Denmark. Less well known are the Vikings of Sweden. Now, the archaeological site of Fröjel on Gotland, a large island in the Baltic Sea around 50 miles east of the Swedish mainland, is helping advance a more nuanced understanding of their activities. While they, too, embarked on ambitious journeys, they came into contact with a very different set of cultures—largely those of Eastern Europe and the Arab world. In addition, these Vikings combined a knack for trading, business, and diplomacy with a willingness to use their own brand of violence to amass great wealth and protect their autonomy.

(Daniel Weiss)

At Fröjel, a Viking Age site on the west coast of Gotland, archaeologists search for evidence of a workshop that included a silver-smelting operation.

Gotland today is part of Sweden, but during the Viking Age, roughly 800 to 1150, it was independently ruled. The accumulation of riches on the island from that time is exceptional. More than 700 silver hoards have been found there, and they include around 180,000 coins. By comparison, only 80,000 coins have been found in hoards on all of mainland Sweden, which is more than 100 times as large and had 10 times the population at the time. Just how an island that seemed largely given over to farming and had little in the way of natural resources, aside from sheep and limestone, built up such wealth has been puzzling. Excavations led by archaeologist Dan Carlsson, who runs an annual field school on the island through his cultural heritage management company, Arendus, are beginning to provide some answers.

Traces of around 60 Viking Age coastal settlements have been found on Gotland, says Carlsson. Most were small fishing hamlets with jetties apportioned among nearby farms. Fröjel, which was active from around 600 to 1150, was one of about 10 settlements that grew into small towns, and Carlsson believes that it became a key player in a far-reaching trade network. “Gotlanders were middlemen,” he says, “and they benefited greatly from the exchange of goods from the West to the East, and the other way around.”

Hoards of the Vikings

Situated between the Swedish mainland and the Baltic states, Gotland was a natural stopping-off point for trading voyages, and Carlsson’s excavations at Fröjel have turned up an abundance of materials that came from afar: antler from mainland Sweden, glass from Italy, amber from Poland or Lithuania, rock crystal from the Caucasus, carnelian from the East, and even a clay egg from the Kiev area thought to symbolize the resurrection of Jesus Christ. And then, of course, there are the coins. Tens of thousands of the silver coins found in hoards on the island came from the Arab world.

Many Gotlanders themselves plied these trade routes. They would sail east to the shores of Eastern Europe and make their way down the great rivers of western Russia, trading and raiding along the way at least as far south as Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, via the Black Sea. Some reports suggest that they also crossed the Caspian Sea and traveled all the way to Baghdad, then the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Entire Viking families are believed to have made their way east. “In the beginning, we thought it was just for trading,” says Carlsson, “but now we see there was a kind of settlement. You find Viking cemeteries far away from the main rivers, in the uplands.” Other evidence of Scandinavian presence in the region is plentiful. As early as the seventh century, there was a Gotlandic settlement at Grobina in Latvia, just inland from the point on the coast closest to Gotland. Large numbers of Scandinavian artifacts have been excavated in northwest Russia, including coin hoards, brooches, and other women’s bronze jewelry. The Rus, the people that gave Russia its name, were made up in part of these Viking transplants. The term’s origins are unclear, but it may have been derived from the Old Norse for “a crew of oarsmen” or a Greek word for “blondes.”

(Courtesy Dan Carlsson)

Combs such as this one, excavated at Fröjel, were made locally of antler imported from mainland Sweden.

To investigate the links between the Gotland Vikings and the East, Carlsson turned his attention to museum collections and archaeological sites in northwest Russia. “It is fascinating how many artifacts you find in every small museum,” he says. “If they have a museum, they probably have Scandinavian artifacts.” For example, at the museum in Staraya Ladoga, east of St. Petersburg, Carlsson found a large number of Scandinavian items, oval brooches from mainland Sweden, combs, beads, pendants, and objects with runic inscriptions, and even three brooches in the Gotlandic style dating to the seventh and eighth centuries. Scandinavians were initially drawn to the area to obtain furs from local Finns, particularly miniver, the highly desirable white winter coat of the stoat, which they would then trade in Western Europe. As time went on, Staraya Ladoga served as a launching point for Viking forays to the Black and Caspian Seas.

These journeys entailed a good deal of risk. The route south from Kiev toward Constantinople along the Dnieper River was particularly hazardous. A mid-tenth-century document by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus tells of Vikings traveling this stretch each year after the spring thaw, which required portaging around a series of dangerous rapids and fending off attacks by local bandits known as the Pechenegs. The name of one of these rapids—Aifur, meaning “ever-noisy” or “impassable”—appears on a runestone on Gotland dedicated to the memory of a man named Hrafn who died there.

People from the East may have traveled back to Gotland with the Vikings as well. At Fröjel, Carlsson has uncovered two Viking Age cemeteries, one dating from roughly 600 to 900, and the other from 900 to 1000. In all, Carlsson has excavated around 60 burials there, and isotopic analysis has shown that some 15 percent of the people whose graves have been excavated—all buried in the earlier cemetery—came from elsewhere, possibly the East.

In their voyages, the Vikings of Gotland are thought to have traded a broad range of goods such as furs, beeswax, honey, cloth, salt, and iron, which they obtained through a combination of trade and violent theft. This activity, though, doesn’t entirely account for the wealth that archaeologists have uncovered. In recent years, Carlsson and other experts have begun to suspect that a significant portion of their trade may have consisted of a commodity that has left little trace in the archaeological record: slaves. “We still have some problems in explaining what made this island so rich,” says Carlsson. “We know from written Arabic sources that the Rus—the Scandinavians in Russia—were transporting slaves. We just don’t know how big their trading in slaves was.”

According to an early tenth-century account by Ibn Rusta, a Persian geographer, the Rus were nomadic raiders who would set upon Slavic people in their boats and take them captive. They would then transport them to Khazaria or Bulgar, a Silk Road trading hub on the Volga River, where they were offered for sale along with furs. “They sell them for silver coins, which they set in belts and wear around their waists,” writes Ibn Rusta. Another source, Ibn Fadlan, a representative of the Abbasid Caliph of Baghdad who traveled to Bulgar in 921, reports seeing the Rus disembark from their boats with slave girls and sable skins for sale. The Rus warriors, according to his account, would pray to their gods: “I would like you to do me the favor of sending me a merchant who has large quantities of dinars and dirhams [Arab coins] and who will buy everything that I want and not argue with me over my price.” Whenever one of these warriors accumulated 10,000 coins, Ibn Fadlan says, he would melt them down into a neck ring for his wife.

It is unclear whether the Vikings transported Slavic slaves back to Gotland, but the practice of slavery appears to have been well established there. The Guta Lag, a compendium of Gotlandic law thought to have been written down in 1220 includes rules regarding purchasing slaves, or thralls. “The law says that if you buy a man, try him for six days, and if you are not satisfied, bring him back,” says Carlsson. “It sounds like buying an ox or a cow.” Burials belonging to people who came from places other than Gotland are generally situated on the periphery of the graveyards with fewer grave goods, suggesting that they may have occupied a secondary tier of society—perhaps as slaves.

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.

Interestingly, when a silver source from the Arab or German world slipped in quality, Jonsson points out, and the Gotlanders rapidly cut off the debased supplies, their contemporaries on mainland Sweden and in areas of Eastern Europe did not. “Word must have spread around the island, saying, ‘Don’t use these German coins anymore!’” says Jonsson. To test imported silver, Gotlanders would shave a bit of the metal with a knife so its contents could be assessed based on color and consistency, says Ny Björn Gustafsson of the Swedish National Heritage Board. He notes that many imported silver items found on Gotland were “pecked” in this way, and that Gotlanders may also have tested imported coins by bending them. By contrast, silver items thought to have been made on Gotland—including heavy arm rings with a zigzag pattern pressed into them—were not generally pecked or otherwise tested. “My interpretation,” Gustafsson says, “is that this jewelry acted as a traditional form of currency and was assumed to contain pure silver.”

These arm rings are among the most commonly found items in Gotland’s hoards, along with coins, and experts had long assumed they were made on the island, but no evidence of their manufacture had been found until Carlsson’s team uncovered a workshop area at Fröjel. “We found the artifacts exactly where they had been dropped,” says Carlsson. There are precious stones: amber, carnelian, garnet. There are half-finished beads, cracked during drilling and discarded. There is elk antler for crafting combs. There is also a large lump of iron, as well as rivets for use in boats, coffins, and storage chests. And, providing evidence of a smelting operation, there are drops of silver.

Researchers found that the metalworkers of Fröjel used an apparatus called a cupellation hearth to transform a suspect source of imported silver, such as coins or ingots, into jewelry or decorated weapons with precisely calibrated silver content. They would melt the silver source with lead and blow air over the molten mélange with a bellows, causing the lead and other impurities to oxidize, separate from the silver, and attach to the hearth lining. The resulting pure silver would then be combined with other metals to produce a desired alloy. The cupellation technique is known from classical times, says Gustafsson, but so far this is the first and only time such a hearth has been found on Gotland. Only one other intact example from the Viking Age has been found in Sweden, at the mainland settlement of Sigtuna.

(Photo by: Ny Björn Gustafsson/The Swedish History Museum)

This imported silver piece found on Gotland shows signs of “pecking,” where a bit of metal was gouged out to test its purity.

Traces of lead and other impurities were found embedded in pieces of the cupellation hearth among the material excavated from the workshop area at Fröjel. The hearth has been radiocarbon dated to around 1100. Also unearthed from the workshop area were fragments of molds imprinted with the zigzag patterns found on Gotlandic silver arm rings, establishing that they were, in fact, made on the island—and that the workshop was the site of the full chain of production, from metal refinement to casting. “We have these silver arm rings in many hoards all over Gotland,” says Carlsson. “But we never before saw exactly where they were making them.”

During the Viking Age, Gotland seems to have been a more egalitarian society than mainland Sweden, which had a structure of nobles led by a king dating from at least the late tenth century. On Gotland, by contrast, farmers and merchants appear to have formed the upper class and, while some were more prosperous than others, they shared in governance through a series of local assemblies called things, which were overseen by a central authority called the Althing. According to the Guta Saga, the saga of the Gotlanders, which was written down around 1220, an emissary from Gotland forged a peace treaty with the Swedish king, ending a period of strife with the mainland Swedes. The treaty, believed to have been established in the eleventh century, required Gotland to pay an annual tax in exchange for continued independence, protection, and freedom to travel and trade.

Stratification did increase on the island as time passed, though. Archaeologists have found that, throughout the ninth and tenth centuries, silver hoards were distributed throughout Gotland, suggesting that wealth was more or less uniformly shared among the island’s farmers. But around 1050, this pattern shifted. “In the late eleventh century, you start to have fewer hoards overall, but, instead, there are some really massive hoards, usually found along the coast, containing many, many thousands of coins,” says Jonsson. This suggests that trading was increasingly controlled by a small number of coastal merchants.

This stratification accelerated near the end of the Viking Age, around 1140, when Gotland began to mint its own coins, becoming the first authority in the eastern Baltic region to do so. “Gotlandic coins were used on mainland Sweden and in the Baltic countries,” says Majvor Östergren, an archaeologist who has studied the island’s silver hoards. Whereas Gotlanders had valued foreign coins based on their weight alone, these coins, though hastily hammered out into an irregular shape, had a generally accepted value. More than eight million of these early Gotlandic coins are estimated to have been minted between 1140 and 1220, and more than 22,000 have been found, including 11,000 on Gotland alone.

(Nanouschka Myrberg Burström)

An example of one of the earliest silver coins minted on Gotland (obverse, left; reverse, right) dates from around 1140.

Gotland is thought to have begun its coinage operation to take advantage of new trading opportunities made possible by strife among feuding groups on mainland Sweden and in western Russia. This allowed Gotland to make direct trading agreements with the Novgorod area of Russia and with powers to the island’s southwest, including Denmark, Frisia, and northern Germany. Gotland’s new coins helped facilitate trade between its Eastern and Western trading partners, and brought added profits to the island’s elite through tolls, fees, and taxes levied on visiting traders. In order to maintain control over trade on the island, it was limited to a single harbor, Visby, which remains the island’s largest town. As a result, the rest of Gotland’s trading harbors, including Fröjel, declined in importance around 1150.

Gotland remained a wealthy island in the medieval period that followed the Viking Age, but, says Carlsson, “Gotlanders stopped putting their silver in the ground. Instead, they built more than 90 stone churches during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.” Although many archaeologists believe that the Gotland Vikings stashed their wealth in hoards for safekeeping, Carlsson thinks that, just as did the churches that were built later, they served a devotional purpose. In many cases, he argues, hoards do not appear to have been buried in houses but rather atop graves, roads, or borderlands. Indeed, some were barely buried at all because, he argues, others in the community knew not to touch them. “These hoards were not meant to be taken up,” he says, “because they were meant as a sort of sacrifice to the gods, to ensure a good harvest, good fortune, or a safer life.” In light of the scale, sophistication, and success of the Gotland Vikings’ activities, these ritual depositions may have seemed to them a small price to pay.

Daniel Weiss

Preserving Our Past, Recording Our Present, Informing Our Future

Ancient and Honorable Clan Carruthers Int Society CCIS LLc

carruthersclan1@gmail.com

Disclaimer Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan International Society CCIS LLC is the official licensed and registered Clan of the Carruthers Family. This Clan is presently registered in the United States and Canada, and represents members worldwide. All content provided on our web pages is for family history use only. The CCIS is the legal owner of all websites, and makes no representation as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on these sites or by following any link provided. The CCIS will not be responsible for any errors or omissions or availability of any information. The CCIS will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. We do not sell, trade or transfer to outside parties any personal identifications. For your convenience, we may provide links to various outside parties that may be of interest to you. The content on CCIS is design to support your research in family history. ( CCIS -LLC copyright 2017 - 2020)

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.

Then a third was built in Fardhem

Then a third was built in Fardhem The de

The de

Ardre Church Ruin, also known as the chapel of Gunfjaun, was built during the 14th century in the medieval marketplace. According to tradition, the church was built in memory of Gunfjaun, the son of a local chieftain named Hafder. It is doubtful whether the church building ever was completed

Ardre Church Ruin, also known as the chapel of Gunfjaun, was built during the 14th century in the medieval marketplace. According to tradition, the church was built in memory of Gunfjaun, the son of a local chieftain named Hafder. It is doubtful whether the church building ever was completed Bara Church Ruin seems to have been abandoned already in the 16th century. In 1588 the local population demanded that it should be re-opened and repaired. The parish was however merged with that of Hörsne Church and Bara Church left to decay. The church was built in the 13th century and shares some characteristics with Anga Church.

Bara Church Ruin seems to have been abandoned already in the 16th century. In 1588 the local population demanded that it should be re-opened and repaired. The parish was however merged with that of Hörsne Church and Bara Church left to decay. The church was built in the 13th century and shares some characteristics with Anga Church.

Gann Church Ruin is a well-preserved ruin of a church probably abandoned during the 16th century. The choir and nave of the ruined church date from the middle of the 13th century, while the tower was added slightly later (late 13th century). The remains were renovated in 1924.

Gann Church Ruin is a well-preserved ruin of a church probably abandoned during the 16th century. The choir and nave of the ruined church date from the middle of the 13th century, while the tower was added slightly later (late 13th century). The remains were renovated in 1924. The ruins of the church dedicated to the Holy Spirit are one of the most unusual of the church ruins in Visby. They consists of an octagonal two-storeyed nave and a protruding choir. The church was erected during the 13th century. According to one theory, the church was built for Bishop Albert of Riga, who is known to have been on Gotland in the early 13th century to gather crusaders and missionaries to go with him to Livonia. The church became the almshouse of Visby in 1532, but by the early 17th century was apparently in a ruinous state and used as a barn.

The ruins of the church dedicated to the Holy Spirit are one of the most unusual of the church ruins in Visby. They consists of an octagonal two-storeyed nave and a protruding choir. The church was erected during the 13th century. According to one theory, the church was built for Bishop Albert of Riga, who is known to have been on Gotland in the early 13th century to gather crusaders and missionaries to go with him to Livonia. The church became the almshouse of Visby in 1532, but by the early 17th century was apparently in a ruinous state and used as a barn. No visible remains exist above ground of the so-called Russian Church. Archaeological excavations carried out in 1971 revealed the foundations of a small church under the floor of a house on Södra kyrkogatan street. It may have been one of possibly two churches for Russian traders in Visby during the Middle Ages

No visible remains exist above ground of the so-called Russian Church. Archaeological excavations carried out in 1971 revealed the foundations of a small church under the floor of a house on Södra kyrkogatan street. It may have been one of possibly two churches for Russian traders in Visby during the Middle Ages The church of Saint Catherine was the church of a Franciscan convent. The convent was founded in 1233 and a first construction period took place c. 1235–1250. During the early 14th century reconstruction work on the church began, and was not finished until 1412, when the church was re-inaugurated. The abbey was disbanded during the 1520s, and the buildings were for a short while used as an almshouse before being completely abandoned.

The church of Saint Catherine was the church of a Franciscan convent. The convent was founded in 1233 and a first construction period took place c. 1235–1250. During the early 14th century reconstruction work on the church began, and was not finished until 1412, when the church was re-inaugurated. The abbey was disbanded during the 1520s, and the buildings were for a short while used as an almshouse before being completely abandoned. The church dedicated to Saint Clement was probably erected during the middle of the 13th century, but its history remains opaque. It was probably preceded by a smaller, 12th-century church. In its present state, it is still considered a typical representative of 13th-century Visby churches

The church dedicated to Saint Clement was probably erected during the middle of the 13th century, but its history remains opaque. It was probably preceded by a smaller, 12th-century church. In its present state, it is still considered a typical representative of 13th-century Visby churches The church was dedicated to the Holy Trinity but called Drotten after an old Norse word meaning Lord or King, i.e. referring to God. It is similar to Sankt Clemens but smaller and probably older. It seems to have been constructed mainly during the 13th and 14th centuries

The church was dedicated to the Holy Trinity but called Drotten after an old Norse word meaning Lord or King, i.e. referring to God. It is similar to Sankt Clemens but smaller and probably older. It seems to have been constructed mainly during the 13th and 14th centuries The church of Saint Nicholas was the abbey church of a Dominican abbey, founded before 1230. Its most famous prior was Petrus de Dacia. The church is possibly older than the abbey; the monks may have acquired an already existing church, or one under construction. Enlargement and reconstruction works were carried out until the late 14th century. The church and abbey were probably destroyed by troops from Lübeck in 1525

The church of Saint Nicholas was the abbey church of a Dominican abbey, founded before 1230. Its most famous prior was Petrus de Dacia. The church is possibly older than the abbey; the monks may have acquired an already existing church, or one under construction. Enlargement and reconstruction works were carried out until the late 14th century. The church and abbey were probably destroyed by troops from Lübeck in 1525

The church was dedicated to Saint George and lies about 300 metres (980 ft) outside the city walls. It was originally tied to an almshouse for lepers nearby. The church is lacking in decorative elements and has therefore been difficult to date. The choir and nave probably date from different periods. The choir is the oldest, perhaps from the late 12th or early 13th century, and the nave may date from the 13th century. The almshouse was shut down in 1542, but the cemetery continued to be used occasionally, e.g. during an outbreak of plague in 1711–12 and following an outbreak of cholera in the 1850s.

The church was dedicated to Saint George and lies about 300 metres (980 ft) outside the city walls. It was originally tied to an almshouse for lepers nearby. The church is lacking in decorative elements and has therefore been difficult to date. The choir and nave probably date from different periods. The choir is the oldest, perhaps from the late 12th or early 13th century, and the nave may date from the 13th century. The almshouse was shut down in 1542, but the cemetery continued to be used occasionally, e.g. during an outbreak of plague in 1711–12 and following an outbreak of cholera in the 1850s. The patron saint of the church was Saint Lawrence. Construction of the church began during the second quarter of the 13th century. It was built by local stonemasons but in an unusual, cross-shaped form. Inspiration for this form probably came from Byzantine architecture and may have reached Gotland following the siege of Constantinople in 1204.

The patron saint of the church was Saint Lawrence. Construction of the church began during the second quarter of the 13th century. It was built by local stonemasons but in an unusual, cross-shaped form. Inspiration for this form probably came from Byzantine architecture and may have reached Gotland following the siege of Constantinople in 1204.

The Gauls were for Numbers and Extent of Land, the greatest People we read of any where; for of that Nation I do reckon the Spaniards, Britains and Irish, to have been, no less than the Inhabitants of the two GalHas, one of which is now called Lombardy, and the other which is now called France, did reach from the Atlantick Ocean, to the Western Banks of the Rhine. And whose Language is spoke no where now but in Wales, Ireland^ and the Highlands of Scotland, and in those Countries in Dialects so different, that I am told the Welsh and Irish do not understand one another.

The Gauls were for Numbers and Extent of Land, the greatest People we read of any where; for of that Nation I do reckon the Spaniards, Britains and Irish, to have been, no less than the Inhabitants of the two GalHas, one of which is now called Lombardy, and the other which is now called France, did reach from the Atlantick Ocean, to the Western Banks of the Rhine. And whose Language is spoke no where now but in Wales, Ireland^ and the Highlands of Scotland, and in those Countries in Dialects so different, that I am told the Welsh and Irish do not understand one another.

I

I

But in Old Norse, the nickname would have been understood as “hairy breeches” or “shaggy trousers.” The Icelander who wrote Ragnar’s Saga in the 13th century explained that Ragnarr got his nickname from the pants he put on to protect himself when fighting a poison-breathing serpent (or dragon): cowhide pants boiled in pitch and rolled in sand.

But in Old Norse, the nickname would have been understood as “hairy breeches” or “shaggy trousers.” The Icelander who wrote Ragnar’s Saga in the 13th century explained that Ragnarr got his nickname from the pants he put on to protect himself when fighting a poison-breathing serpent (or dragon): cowhide pants boiled in pitch and rolled in sand.