CLAN CARRUTHERS INT SOCIETY CCIS

CLAN CARRUTHERS – A VISIT OF ST OLAF TO TREATY WITH THE KING

The Visit of St Olaf

1 BACKGROUND TO THE VISIT

The history of the conversion of Gotland has been extensively

studied and there are several theories concerning its approximate

date.2 One of the central episodes in Guta saga is that concerning

2 Both Ochsner (1973) and Pernler (1977) have produced detailed analyses of the evidence surrounding the conversion of Gotland to Christianity.

While they both consider the role played by St Olaf to be exaggerated,

Pernler rejects all suggestion of a full conversion to Christianity before the

eleventh century. The fact that Guta saga gives an inconsistent account

and chronology, however, seems to support such a possibility. First Olaf

arrives and converts Ormika, then Botair, in a seemingly totally heathen

community, builds two churches, which are followed by others when

Gotland becomes generally Christian. Finally, after a delay, Gotland is

incorporated into the see of Linköping. Ochsner (1973, 22) points to

graves without grave goods dating from the eighth century as an indication

of the possible commencement of conversion and this view is also put

St Olaf’s visit. The story, as it is told, contradicts the explicit

statement in Heimskringla, Óláfs saga helga (ÍF XXVII, 328), that

Olaf travelled um sumarit ok létti eigi, fyrr en hann kom austr í

Garðaríki á fund Jarizleifs konungs ok þeira Ingigerðar dróttningar,

although Bruno Lesch (1916, 84–85) argues that Olaf did stop in

Gotland on that journey and that his stay was simply unknown to

Snorri. Guta saga does not, understandably, mention the visit in

1007, during which the twelve-year-old Olaf intimidated the Gotlanders

into paying protection money and subsequently stayed the winter;

see Óláfs saga helga (ÍF XXVII, 9). On that occasion he proceeded

eastwards on a raid on Eysýsla (Ösel), the Estonian Saaremaa. It

has been suggested that the visit described in Guta saga is actually

the one mentioned in Óláfs saga helga (ÍF XXVII, 343), when Olaf

is said to have visited Gotland on his way home from Russia in the

spring of 1030, a view supported by Finnur Jónsson (1924, 83) as

the correct one. It does not seem very likely, however, that Olaf

would make a prolonged break in his journey at that time. Other

sources do not mention Gotland at all in this connection (e. g.

Fagrskinna, ÍF XXIX, 198–199), and in those that do, Olaf only

seems to have stopped for news of Earl Hákon’s flight and to await

a favourable wind. Clearly not all the accounts of the journey to

Russia can be correct and it is probably impossible to discover

which, if any them, is the true one. It is, however, very likely that

St Olaf visited Gotland while he was king, since a coin with his

image on it was found at Klintehamn, Klinte parish, on the west

coast of Gotland, and that this visit would have given rise to

forward by Nerman (1941a, 39–40), who argues from artefacts that have

been found that there was a conversion, albeit not a complete one, in the

eighth or ninth century, as a result of a missionary effort from Western

Europe, followed by a reversion, such as occurred at Birka, in the tenth,

and a re-introduction of Christianity in the eleventh century; cf. Stenberger,

1945, 97. Holmqvist (1975, 35–39) has also noted possible Christian

motifs in early artefacts; cf. Note to 2/8. It is remarkable that neither

Rimbert’s biography of Ansgar nor Adam of Bremen’s writings mention

Gotland, which could mean that the Hamburg–Bremen mission did not

take any substantial part in the conversion of Gotland; cf. Holmqvist,

1975, 39, 51, 55; Pernler, 1977, 43–44. Pernler, throughout, argues for a

gradual conversion, culminating in the incorporation of Gotland into the

see of Linköping, rather than a concerted mission; see Notes to 8/1–10,

8/7–8, 8/14, 8/28–29, 10/21.

traditions; cf. Dolley, 1978. The missionary visit to Gotland, if it

occurred, can be placed between 1007 or 1008, when Olaf made

his earlier visit, and 1030. Given the discrepancy between the

accounts in Heimskringla and Guta saga, it seems unlikely that

Snorri was the author’s source for this episode and there is internal

evidence that some sort of oral tale was the primary inspiration;

see pp. xl–xli. Cf. also SL IV, 306–311 and references; Note to 8/4.

Akergarn, in Hellvi parish, where Olaf is said to have landed, is

now called S:t Olofsholm. Although the account in Guta saga may

have originated in an early oral tradition, other traditions exist,

which make it difficult to identify those which were current at the

time Guta saga was written. For example, there is a tradition from

S:t Olofsholm, recorded by Säve (1873–1874, 249), of Olaf either

washing his hands or baptising the first Gotlanders he came across

in a natural hollow in a rock. This hollow is still visible and is

called variously Sankt Oles tvättfat and Sankt Oläs vaskefat; see

Gotländska sägner 1959–1961, II, 391; Palmenfelt, 1979, 116–

118; Sveriges Kyrkor: Got(t)land, 1914–1975, II, 129. Tradition

further holds that there is always water in the hollow, but such tales

are common in relation to famous historical figures.

Strelow (1633, 129–132) includes a number of elements in his

account of St Olaf’s visit that in all probability had their origins

later than Guta saga. He mentions (1633, 132) the apparent existence at Kyrkebys, in the parish of Hejnum, of a large, two-storey,

stone house, called Sankt Oles hus, in which Olaf’s bed, chair and

hand basin (Haandfad ), set in the wall, could be seen. According

to Wallin (1747–1776, I, 1035) these were still visible in the

eighteenth century, although Säve (1873–1874, 249–250) admits

that by the nineteenth century the original building was no longer

there, the stone having been used for out-buildings. Wallin also

says in the same context that for a long time one of Olaf’s silver

bowls, his battle-axe and three large keys could be found, but this

contention is in all probability secondary to Guta saga. Of the

wall-set hand basin mentioned by Wallin, Säve (1873–1874, 250)

says that what was intended was probably a vessel for holy water

but that the object that was referred to in his time was a large

limestone block with a round hollow in it, which was much more

likely to have been an ancient millstone.

On the west coast of Fårö, south of Lauter, there is also a S:t

Olavs kyrka and there was a tradition amongst the local population,

recorded by Säve (1873–1874, 252), that Olaf landed near there, at

Gamlehamn (Gambla hamn). This is now shut off from the sea by

a natural wall of stones, boulders and gravel. The stone includes

gråsten, which is not otherwise found in the area, and which Olaf

is said to have brought with him. Some 70 metres south of the

harbour, Säve continues, there was a nearly circular flattened low

dry-stone wall surrounding Sant Äulos körka, or a remnant of it.

The church-shaped wall was still visible with what could have been

the altar end pointing more or less eastwards and human remains

in the north of the enclosure. Fifty metres to the east and up a slope

was, according to Säve, Sant Äulos kälda, which is also said never

to dry up, and which was traditionally said to have been used to baptise

the first heathens Olaf encountered. Nearby on the beach are two

abandoned springs, Sant Äulos brunnar. They are about two metres

apart and the saint is said to have been able to lie with a hand in

each, which feat put an end to a severe drought; see Säve, 1873–1874,

253, after Wallin. A further addition to this folklore is the mention

of a hollow in the chalk cliff a little to the north of this area, about

1.8 × 0.9 metres, called Sant Äulos säng. Säve saw all these

features and discussed them with the local people. They are considered by Fritzell (1972, 40) to be related to a heathen cult associated

with a local spring, which has a depression resembling a bed or a bath.

There is no mention in Guta saga of any of these traditions, and

it seems probable that they are later inventions to give, in W. S.

Gilbert’s words, ‘artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and

unconvincing narrative’. The wealth of tradition on Fårö, as recorded by Säve, and the fact that the more natural landing-site for

Olaf would be on the west coast if he were coming from Norway

as Guta saga states, could mean, however, that he did at some time

land in Gotland and effect a number of conversions.

Strelow (1633, 131) carries an altogether more violent version of

the conversion and gives an account of a battle at a place he calls

Lackerhede (Laikarehaid in the parish of Lärbro, about 10 kilometres north-west of S:t Olofsholm), which resulted in the acceptance of Christianity by the Gotlanders. This account has been

generally rejected by scholars, and was certainly not a tradition

that the author of Guta saga used, although Säve (1873–1874, 248)

suggests that Olaf might have applied some force to convert a

small number of the islanders on his way eastwards. The legend could,

as Pernler (1977, 14–15) suggests, have arisen through confusion

xl Guta saga

with the battle between the Gotlanders and Birger Magnusson at

Röcklingebacke, both sites being just east of Lärbro parish church.

Many of the details mentioned, such as the existence of the iron

ring to which Olaf was said to have tied up his ship, are clearly not

factual; cf. Strelow, 1633, 130.

The greatest mystery surrounding the missionary visit relates to

the fact that nowhere in the mainstream of the Olaf legend is the

conversion of so important a trading state as Gotland mentioned,

either in Snorri or elsewhere. This seems strange, if Olaf did in fact

convert Gotland, and points to the episode in Guta saga being the

product of local tradition, centred around a number of place-names

and other features, as well as the likelihood that Olaf did actually

visit Gotland at least once, if not twice, and that he was taken as

Gotland’s patron saint. The importance of St Olaf to the medieval

Gotlanders is emphasised by their dedicating their church in Novgorod

to his name. There is also a suggestion that the church laws in Guta

lag resemble those of Norway and that they could have been formulated

under the direct or indirect influence of St Olaf; cf. SL IV, 310.

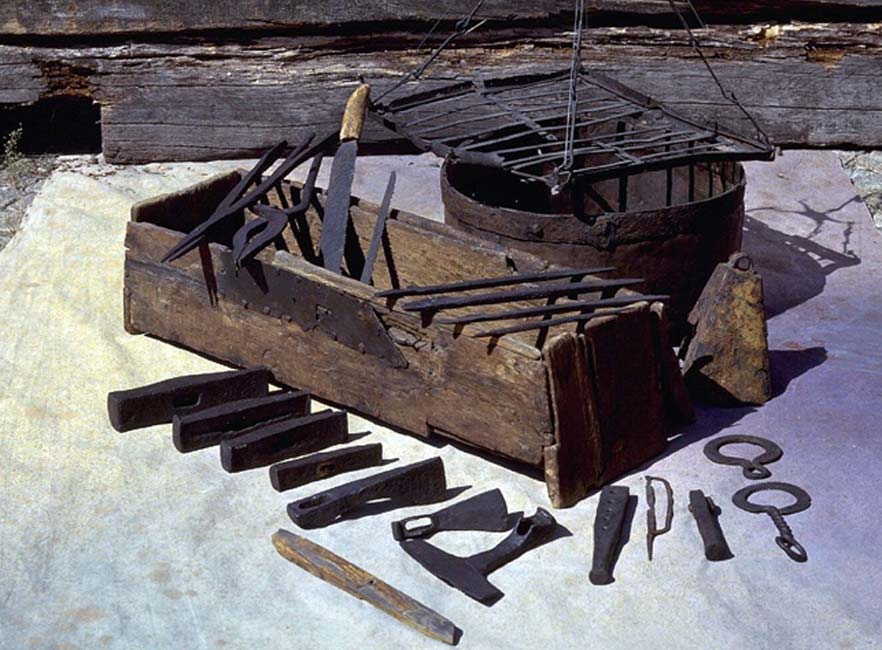

ORMIKA’S GIFTS

The motif of important leaders who start as adversaries exchanging

gifts when their relationship changes is a common one, but it is

worth noting the iconographical connection between the braiþyx

and bulli and St Olaf, and the fact that the author of Guta saga

must have seen images of the saint with just those objects. The

description of the exchange of gifts between Olaf and Ormika of

Hejnum raises the possibility of one or a pair of drinking vessels

and/or a battle-axe being extant at some time, which the author was

led to believe had some connection with this incident. Perhaps he,

or someone known to him, had seen a bowl of the type called a

bulli, which was said to have been a gift from St Olaf to a Gotlander

on the occasion of his acceptance of Christianity. One of St Olaf’s

attributes, which he is depicted as carrying in some images, is a

ciborium (the lidded bowl in which the communion host is carried). Nils Tiberg (1946, 23) interprets the bulli as just such a

covered vessel, and Per Gjærder (KL, s. v. Drikkekar) states that the

bolli type of drinking-bowl not only had a pronounced foot but was

sometimes furnished with a lid. Such a vessel could have been in

the possession of the chapel at Akergarn and have been associated

with St Olaf’s visit. The braiþyx is the other attribute of St Olaf and

it would be even more natural that a connection should be made

between St Olaf and such a weapon. Perhaps one was kept in the

church at Akergarn at the time the author wrote the text, and he

linked the building to an earlier chapel on the site, one said to have

been built by Ormika. There might also have been a tradition that

a man named Ormika travelled the 20 kilometres from his home

south of Tingstäde träsk to meet St Olaf, some considerable time

after he had landed, at the request of the people of his district. The

fusing of the two traditions then produced the version of events that

survives. The interpretation of the name Ormika as a feminine

form, which led Strelow (1633, 132) to represent the character as

female, is almost certainly incorrect. It is possible that the Gotlandic

pronunciation of the feminine personal pronoun, which is more

like that of the masculine than on the Swedish mainland, combined

with the -a ending, led to confusion, particularly if the story had

been transmitted orally.

In the light of Heimskringla, however, another interpretation can

be put on the Ormika episode: the mention of the giving by Ormika

of 12 wethers ‘and other costly items’ to Olaf could possibly be

regarded as the payment of some sort of tribute, as described by

Snorri. It might be that the tradition that protection money was

paid to Olaf at one time or another was combined with a tradition

that he occasionally offered gifts in return, perhaps merely as a

pledge of good faith. A gift of sheep would no doubt be a natural

one from a Gotlander, but equally sheep have been a substitute for

money in many societies, ancient coins being marked with the

image of a sheep. Fritzell (1972, 30) points out that the number 12

is associated with taxes extracted by the Danes in the Viking

period. It may also be linked to the 12 hundari proposed by

Hyenstrand (1989, 119). The name Ormika occurs in an inscription

found at Timans in the parish of Roma; see Note to 8/3.

THE ORATORY AT AKERGARN

According to Guta saga Ormika gierþi sir bynahus i sama staþ,

sum nu standr Akrgarna kirkia. A chapel was certainly in existence

at Akergarn by the thirteenth century, since it is mentioned in

several letters from bishops of Linköping; see Note to 8/9. It was

in ruins by the seventeenth century but had by that time become the

centre for a number of traditions about St Olaf to be found in

contemporary folklore, and in Strelow’s description of the conversion

xlii Guta saga

of Gotland; see SL IV, 308, 311; Sveriges Kyrkor: Got(t)land,

1914–1975, II, 128–130.

P Church building

1 BOTAIR AND LIKKAIR

There is in Guta saga what might be considered to be an alternative

account of the conversion, not involving St Olaf and Ormika, but

Botair and his father-in-law, Likkair. In this version, Gotlandic

merchants come into contact with the Christian religion as a result

of their trading voyages, and some are converted. This intercourse

has been dated to the tenth century, that is before St Olaf’s first

visit to Gotland; cf. SL IV, 312. Priests are brought back to Gotland

to serve these converts and Botair of Akebäck is said to have had

the first church built, at Kulstäde. According to tradition, the

foundations of the church can still be discerned, lying SW–NE and

with dimensions of 30 metres by 12 metres; see Pernler, 1977, 20

and references. This identification was called into question as early

as 1801 by C. G. G. Hilfeling (1994–1995, II, 145–146) who

considers the remains to be comparable to that of a so-called

kämpargrav, and this opinion is to a certain extent supported by

Fritzell (1974, 14–16), on account of the generous dimensions and

the existence of a door in the west gable. Fritzell maintains that

Kulstäde was the site of the church mentioned in Guta saga, but

that it was also a cult site prior to this. Pernler, however (1977, 20),

and with some justification, is wary of making such an assumption,

when there is no evidence of the actual date of the event described.

Together with Gustavson (1938, 20), he suggests that the churchbuilding story could have its basis in a place-name saga. If this

were the case, it is possible that the saga formed the basis of the

account in Guta saga.

Botair builds another church near Vi, just when his heathen

countrymen are having a sacrifice there. Gustavson (1938, 36) cites

Lithberg as saying that no place of sacrifice existed near Visby and

that the passage in Guta saga is based on folk-etymology. Although Hellquist, despite his earlier doubts (1918, 69 note), noted

by Knudsen (1933, 34), accepts the traditional view and dismisses

other interpretations, it may still be disputed whether the name

Visby was connected with the existence of a pagan holy site or vi

in the area. It is possible that the author of Guta saga had heard a

tradition about the building of the first church that was allowed to

stand in Gotland and placed it, not unnaturally, in the neighbourhood of Visby; see Hellquist, 1980, s. v. Vi; 1929–1932, 673. This

argument seems defensible, despite Olsson’s assertion (1984, 20)

that it ‘förefaller inte särskilt troligt, att författaren skulle ha diktat

ihop dessa uppgifter, inspirerad av namnet Visby’. The idea that the

first Christian church that was allowed to stand should have been

built on the site of a pagan holy place has not been universally

accepted and, in his study of stafgarþr place-names, Olsson (1976,

115, note 58; 121) specifically rejects the link between cult places

and the later building of churches. In an earlier thesis (1966, 131–

133, 237–238, 275) based largely on sites in Denmark, Olaf Olsen

came to the conclusion that great care must be taken in assuming

a continuity in the use of sites for burial from the Bronze Age

through the Viking Age, particularly when based on place-names,

but that in certain cases, the church at Gamla Uppsala for example,

there might have been a transition from immediately pre-Christian

to Christian use; cf. Foote and Wilson, 1979, 417–418; Lindqvist,

1967, 236. There are, however, several examples of churches being

built on the sites of Stone-Age and Bronze-Age barrows. These

barrows might have been used by Viking-Age pagans as cult sites

(rather in the way that stafgarþar were possibly used), but when

churches were built there, it could have been the fact that they were

situated on high ground that led to the choice of site, rather than

any other reason; cf. Olsen, 1966, 274–275. Considerable rebuilding has taken place on the site of the churches of S:t Hans and

S:t Per in Visby and it is possible that some remains (graves,

for example) carried a tradition of there having been an older

church there; see Notes to 8/27 and 8/28. Any wooden church

would of course long since have disappeared and Wessén (SL IV,

312) suggests that it would probably have dated from a period prior

to the foundation of Visby itself. Cf. also Notes to 8/18 and

8/25–26.

The story in Guta saga of Likkair, and his success in saving both

his son-in-law and his church, contains certain inconsistencies.

The reason he gives to the heathens that they should not burn this

edifice is that it is in Vi, presumably a heathen holy place. This

would not seem to be a very plausible reason to give, and to be

even less likely for the heathens to accept; cf. Note to 8/18. The

fact that the church is said to be dedicated to All Saints, whereas

the church present in the author’s day, of which part of a wall is

xliv Guta saga

still visible as a ruin, incorporated into S:t Hans’s ruin, was called

S:t Pers also suggests that there may have been a half-understood

tradition, perhaps not related to Visby at all. It is possible, however, that the place-name Kulasteþar gave rise to oral tradition

about the building of a church there, which was reduced to charcoal, and that Stainkirchia relates to a later stone church of a more

permanent nature. Botair’s second church was also obviously wooden,

since it was threatened with the same fate as the first. Likkair

seems to have been a local hero, and there are other tales about

him; see Notes to 8/22 and 8/23. Conversion stories tend naturally

to be told about people who are presented as having the respect of

both the converted and heathen communities. Another example of

this is Þorgeirr Ljósvetningagoði in Njáls saga (ch. 105; ÍF XII,

270–272). Likkair’s soubriquet, snielli, is reminiscent of those

given to wise counsellors in the Icelandic sagas and he may have

been the equivalent of a goði, since he is said to have had ‘most

authority’ at that time.

There appear to be no place-names that might have suggested the

name Botair to the author and although the farm name Lickedarve

from Fleringe parish in the north-east of Gotland could be connected with someone called Likkair, he might not be the character

referred to in the story; cf. Olsson, 1984, 41, 131 and Note to 8/22.

In the churchyard of Stenkyrka church, however, there is an impressive slab which is known as Liknatius gravsten; see Hyenstrand,

1989, 129. It might indicate a medieval tradition connecting Likkair

to Stenkyrka. There is at least one other tale, certainly secondary

to Guta saga, told about Likkair Snielli, and several place-names

(e. g. Lickershamn, a harbour in the parish of Stenkyrka on the

north west coast of Gotland) are said to be associated with him.

The folk-tale, recorded by Johan Nihlén in 1929, concerns Likkair’s

daughter and the foreign captive, son of his defeated opponent,

whom he brought home as a slave. The daughter falls in love with

the foreigner and Likkair is violently opposed to the relationship,

not least because the young man is a Christian, and he has already

lost one of his daughters (Botair’s wife) to the new faith. He has his

daughter lifted up to the top of a high cliff and the prisoner is told

that if he can climb up and retrieve her, he will be given her hand,

otherwise he will be killed. The young man manages the climb, but

as he comes down with the girl in his arms, Likkair shoots him with

an arrow and they both fall into the sea. At Lickershamn there is

a cliff called Jungfrun which is said to be the one from which the

lovers fell; see Nihlén, 1975, 102–104. Wallin records a different

tale in connection with this rock, however, relating it to a powerful

and rich maiden called Lickers smällä, said to have built the church

at Stenkyrka; see Gotländska sägner, 1959–1961, II, 386. Lickershamn

is about five kilometres north-west of Stenkyrka itself but, although it is tempting to regard this as suggestive of a connection

between Stenkyrka and Likkair, it is probable that the name of the

coastal settlement is secondary to the tradition and of a considerably later origin than the parish name.

2 OTHER CHURCHES

Church building is one of the categories of tale that Schütte (1907,

87) mentions as occurring in ancient law texts, forming part of the

legendary history that is often present as an introduction. In Guta

saga churches are assigned to the three divisions of the country,

followed by others ‘for greater convenience’. The three division

churches were clearly meant to replace the three centres of sacrifice and in fact were not the first three churches built. (The one

built by Botair in Vi was the first to be allowed to stand, we are

told.) There could well have been some oral tradition behind this

episode, linked to the division of the island, and it is hard to believe

that everything would have happened so tidily in reality. As no

bishops have been mentioned at this stage, it is difficult to understand who could have consecrated these churches, and it seems

more likely that they started off as personal devotional chapels,

commissioned by wealthy converts such as Likkair. There are no

authenticated remains of churches from the eleventh century, but

there were certainly some extant in the thirteenth century when

Guta saga was written. The tradition of rich islanders building

churches, and the relatively high number of those churches (97)

highlights the wealth of medieval Gotland; cf. SL IV, 313.

Church-building stories form an important part of early Christian literature and there is often a failed attempt (sometimes more

than one) to build a church followed by a successful enterprise at

a different site; cf. KL, s. v. Kyrkobyggnassägner and references.

The combination of these motifs with a possible oral tradition, and

the placing of the three treding churches, has been built by the

author into a circumstantial narrative, which to some extent conflicts

with the Olaf episode in accounting for the conversion of Gotland.

xlvi Guta saga

So far the possible sources discussed have been in the nature of

oral traditions or literary parallels as models. The remainder of

Guta saga is of a more historical character and the suggested

sources for these sections tend to be in the form of legal or ecclesiastical records, even if in oral form.

Q Conversion of Gotland as a Whole

Within the description of the early church-building activity is a

short statement concerning the acceptance of Christianity by the

Gotlanders in general. It is reminiscent of the passage describing

the subjugation to the Swedish throne. The one states that gingu

gutar sielfs viliandi undir suia kunung, the other that the Gotlanders

toku þa almennilika viþr kristindomi miþ sielfs vilia sinum utan

þuang. The similarity leads one to presume that a written or oral

model lies behind both, particularly as the statements differ in style

from the surrounding narrative. The models do not, however, appear

to have survived.

R Ecclesiastical arrangements

1 TRAVELLING BISHOPS

The formula for the acceptance of Christianity mentioned above

appears to come out of sequence in the text since the next episode,

that of the travelling bishops, apparently takes place before the

general conversion. If, as has been suggested, the author was a

cleric, he might have felt it necessary to legitimise Gotland’s early

churches by inserting a tradition, of which he had few details, to

explain the consecration issue. Gotland was a stepping-stone on

the eastwards route as described in the Notes to 4/6, 8/10 and 10/16

and it would be more than likely that travelling bishops stopped

there. If so, they might have been unorthodox, of the type mentioned in Hungrvaka (1938, 77). Wessén (SL IV, 318) suggests that

the importance of Gotland as a staging post might have emerged at

the same time as its trading importance, in the twelfth century. The

consecration of priests is not mentioned, but there would be little

point in having hallowed churches and churchyards if there were

no priests to say holy office in the churches or bury the dead in the

churchyards. The priests whom the Gotlanders brought back with

them from their travels would hardly be sufficient to satisfy a

growing Christian community, however. The obvious explanations

for the omission are, either that the author did not know and had

no available source to help him, or did not think it of importance.

The possibility of there having been a resident bishop on Gotland in

the Middle Ages is discussed by Pernler (1977, 46–56), but he reaches

the conclusion that there is no evidence to support such an idea.

2 ARRANGEMENTS WITH THE SEE OF LINKÖPING

The formal arrangements made with the see of Linköping read like

a more or less direct copy of an agreement drawn up at the time.

There is a considerable amount of contemporary corroboration for

the arrangements, including a letter dated around 1221 from Archbishop Andreas Suneson of Lund and Bishops Karl and Bengt of

Linköping; cf. DS I, 690, no. 832; SL IV, 313–314. The letter

enables one to interpret more accurately the Gutnish text. Again,

the author of Guta saga lays emphasis on the voluntary nature of

the arrangement, a stress probably intended to demonstrate Gotland’s

effective independence from the Swedish crown. The fact that the

financial arrangements between the Gotlanders and the bishop of

Linköping were relatively lenient to the former, in comparison to

those with other communities in the same see, seems to support the

author’s claim; cf. Schück, 1945, 184. The actual dating of the

incorporation of Gotland into the see of Linköping is less certain,

but could not be much earlier than the middle of the twelfth

century. The manuscript Codex Laur. Ashburnham (c.1120) names

both Gotland and ‘Liunga. Kaupinga’, but there is some doubt as

to whether the latter refers to Linköping at all; cf. Delisle, 1886,

75; DS, Appendix 1, 3, no. 4; Envall, 1950, 81–93; 1956, 372–385;

Gallén, 1958, 6, 13–15. It seems probable that Gotland was incorporated into the see in the second half of the twelfth century,

during the time of Bishop Gisle, but there is no direct evidence of

the date, or of the relationship between this event and the absorption of Gotland into the Swedish kingdom; cf. Pernler, 1977, 65.

Bishop Gisle, in collaboration with King Sverker the Elder and his

wife, introduced the Cistercian order into Sweden. The Cistercian

monastery of the Beata Maria de Gutnalia at Roma was instituted,

although by whom is not known, on September 9th, 1164 as a

daughter house to Nydala in Småland; cf. Pernler, 1977, 57, 61–62;

SL IV, 306 and references; Note to 6/21–22. It seems possible that

Gisle was behind the foundation, and that Gotland had by that time

been included into the see of Linköping. It is not certain that Gisle

xlviii Guta saga

was the first bishop of the see, but there is no other contrary

evidence than a list of bishops, dating from the end of the fourteenth century and held in Uppsala University library. This list

mentions two earlier bishops (Herbertus and Rykardus) but nothing further is known of them; see Schück, 1959, 47–49; Pernler,

1977, 58; SRS III, 102–103, no. 5; 324, no. 15.

S Levy arrangements

The establishment of an obligation to supply troops and ships to

the Swedish crown and the levy terms associated with this obligation have been dated by Rydberg (STFM I, 71) to around 1150, but

placed rather later by Yrwing (1940, 58–59). Once again, contemporary letters corroborate to a large degree the content of Guta

saga in respect of this material. Despite several protestations within

Guta saga of the independence of Gotland from foreign domination, the other statutes mentioned at the end of the text suggest that

this independence was being slowly eroded, and that Gotland was

gradually becoming a province of Sweden. The ledung was mainly

called out for crusades against the Baltic countries, and there are

several contemporary sources recording these expeditions and the

reaction of the Gotlanders to the summons; see Notes to 12/23.

Wessén points out (SL IV, 319) that Magnus Ladulås in 1285

established a different arrangement, according to which a tax was

payable annually, rather than merely as a fine for failing to supply

the stipulated ships when they were summoned; cf. DS I, 671–672,

no. 815; STFM I, 290–291, no. 141. Wessén and other scholars use

the fact that the author of Guta saga does not seem aware of this

change to postulate that he must have been writing before 1285,

Preserving Our Past, Recording Our Present, Informing Our Future

Ancient and Honorable Clan Carruthers Int Society CCIS LLc

carruthersclan1@gmail.com carrothersclan@gmail.com

You can find us on facebook at :

https://www.facebook.com/CarruthersClan/

Disclaimer Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan International Society CCIS LLC is the official licensed and registered Clan of the Carruthers Family. This Clan is presently registered in the United States and Canada, and represents members worldwide. All content provided on our web pages is for family history use only. The CCIS is the legal owner of all websites, and makes no representation as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on these sites or by following any link provided. The CCIS will not be responsible for any errors or omissions or availability of any information. The CCIS will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. We do not sell, trade or transfer to outside parties any personal identifications. For your convenience, we may provide links to various outside parties that may be of interest to you. The content on CCIS is design to support your research in family history. ( CCIS -LLC copyright 2017 - 2020)

Then a third was built in Fardhem

Then a third was built in Fardhem The de

The de

Ardre Church Ruin, also known as the chapel of Gunfjaun, was built during the 14th century in the medieval marketplace. According to tradition, the church was built in memory of Gunfjaun, the son of a local chieftain named Hafder. It is doubtful whether the church building ever was completed

Ardre Church Ruin, also known as the chapel of Gunfjaun, was built during the 14th century in the medieval marketplace. According to tradition, the church was built in memory of Gunfjaun, the son of a local chieftain named Hafder. It is doubtful whether the church building ever was completed Bara Church Ruin seems to have been abandoned already in the 16th century. In 1588 the local population demanded that it should be re-opened and repaired. The parish was however merged with that of Hörsne Church and Bara Church left to decay. The church was built in the 13th century and shares some characteristics with Anga Church.

Bara Church Ruin seems to have been abandoned already in the 16th century. In 1588 the local population demanded that it should be re-opened and repaired. The parish was however merged with that of Hörsne Church and Bara Church left to decay. The church was built in the 13th century and shares some characteristics with Anga Church.

Gann Church Ruin is a well-preserved ruin of a church probably abandoned during the 16th century. The choir and nave of the ruined church date from the middle of the 13th century, while the tower was added slightly later (late 13th century). The remains were renovated in 1924.

Gann Church Ruin is a well-preserved ruin of a church probably abandoned during the 16th century. The choir and nave of the ruined church date from the middle of the 13th century, while the tower was added slightly later (late 13th century). The remains were renovated in 1924. The ruins of the church dedicated to the Holy Spirit are one of the most unusual of the church ruins in Visby. They consists of an octagonal two-storeyed nave and a protruding choir. The church was erected during the 13th century. According to one theory, the church was built for Bishop Albert of Riga, who is known to have been on Gotland in the early 13th century to gather crusaders and missionaries to go with him to Livonia. The church became the almshouse of Visby in 1532, but by the early 17th century was apparently in a ruinous state and used as a barn.

The ruins of the church dedicated to the Holy Spirit are one of the most unusual of the church ruins in Visby. They consists of an octagonal two-storeyed nave and a protruding choir. The church was erected during the 13th century. According to one theory, the church was built for Bishop Albert of Riga, who is known to have been on Gotland in the early 13th century to gather crusaders and missionaries to go with him to Livonia. The church became the almshouse of Visby in 1532, but by the early 17th century was apparently in a ruinous state and used as a barn. No visible remains exist above ground of the so-called Russian Church. Archaeological excavations carried out in 1971 revealed the foundations of a small church under the floor of a house on Södra kyrkogatan street. It may have been one of possibly two churches for Russian traders in Visby during the Middle Ages

No visible remains exist above ground of the so-called Russian Church. Archaeological excavations carried out in 1971 revealed the foundations of a small church under the floor of a house on Södra kyrkogatan street. It may have been one of possibly two churches for Russian traders in Visby during the Middle Ages The church of Saint Catherine was the church of a Franciscan convent. The convent was founded in 1233 and a first construction period took place c. 1235–1250. During the early 14th century reconstruction work on the church began, and was not finished until 1412, when the church was re-inaugurated. The abbey was disbanded during the 1520s, and the buildings were for a short while used as an almshouse before being completely abandoned.

The church of Saint Catherine was the church of a Franciscan convent. The convent was founded in 1233 and a first construction period took place c. 1235–1250. During the early 14th century reconstruction work on the church began, and was not finished until 1412, when the church was re-inaugurated. The abbey was disbanded during the 1520s, and the buildings were for a short while used as an almshouse before being completely abandoned. The church dedicated to Saint Clement was probably erected during the middle of the 13th century, but its history remains opaque. It was probably preceded by a smaller, 12th-century church. In its present state, it is still considered a typical representative of 13th-century Visby churches

The church dedicated to Saint Clement was probably erected during the middle of the 13th century, but its history remains opaque. It was probably preceded by a smaller, 12th-century church. In its present state, it is still considered a typical representative of 13th-century Visby churches The church was dedicated to the Holy Trinity but called Drotten after an old Norse word meaning Lord or King, i.e. referring to God. It is similar to Sankt Clemens but smaller and probably older. It seems to have been constructed mainly during the 13th and 14th centuries

The church was dedicated to the Holy Trinity but called Drotten after an old Norse word meaning Lord or King, i.e. referring to God. It is similar to Sankt Clemens but smaller and probably older. It seems to have been constructed mainly during the 13th and 14th centuries The church of Saint Nicholas was the abbey church of a Dominican abbey, founded before 1230. Its most famous prior was Petrus de Dacia. The church is possibly older than the abbey; the monks may have acquired an already existing church, or one under construction. Enlargement and reconstruction works were carried out until the late 14th century. The church and abbey were probably destroyed by troops from Lübeck in 1525

The church of Saint Nicholas was the abbey church of a Dominican abbey, founded before 1230. Its most famous prior was Petrus de Dacia. The church is possibly older than the abbey; the monks may have acquired an already existing church, or one under construction. Enlargement and reconstruction works were carried out until the late 14th century. The church and abbey were probably destroyed by troops from Lübeck in 1525

The church was dedicated to Saint George and lies about 300 metres (980 ft) outside the city walls. It was originally tied to an almshouse for lepers nearby. The church is lacking in decorative elements and has therefore been difficult to date. The choir and nave probably date from different periods. The choir is the oldest, perhaps from the late 12th or early 13th century, and the nave may date from the 13th century. The almshouse was shut down in 1542, but the cemetery continued to be used occasionally, e.g. during an outbreak of plague in 1711–12 and following an outbreak of cholera in the 1850s.

The church was dedicated to Saint George and lies about 300 metres (980 ft) outside the city walls. It was originally tied to an almshouse for lepers nearby. The church is lacking in decorative elements and has therefore been difficult to date. The choir and nave probably date from different periods. The choir is the oldest, perhaps from the late 12th or early 13th century, and the nave may date from the 13th century. The almshouse was shut down in 1542, but the cemetery continued to be used occasionally, e.g. during an outbreak of plague in 1711–12 and following an outbreak of cholera in the 1850s. The patron saint of the church was Saint Lawrence. Construction of the church began during the second quarter of the 13th century. It was built by local stonemasons but in an unusual, cross-shaped form. Inspiration for this form probably came from Byzantine architecture and may have reached Gotland following the siege of Constantinople in 1204.

The patron saint of the church was Saint Lawrence. Construction of the church began during the second quarter of the 13th century. It was built by local stonemasons but in an unusual, cross-shaped form. Inspiration for this form probably came from Byzantine architecture and may have reached Gotland following the siege of Constantinople in 1204.

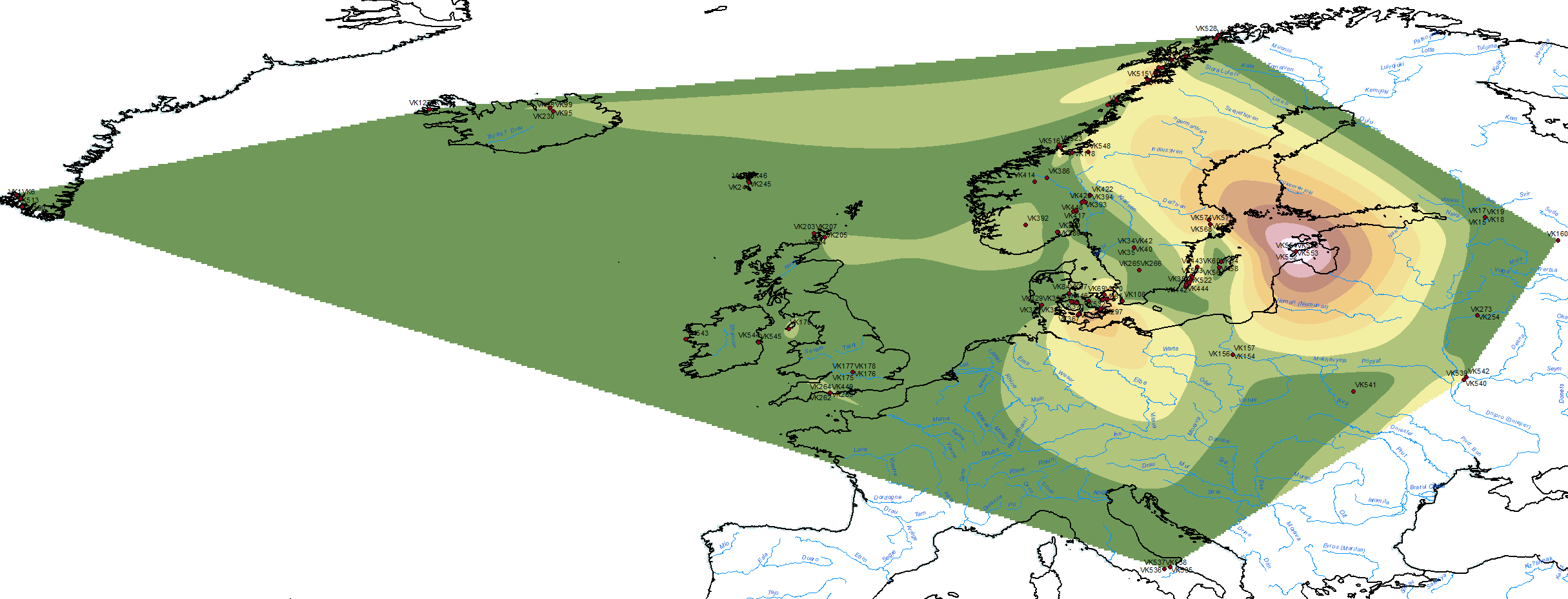

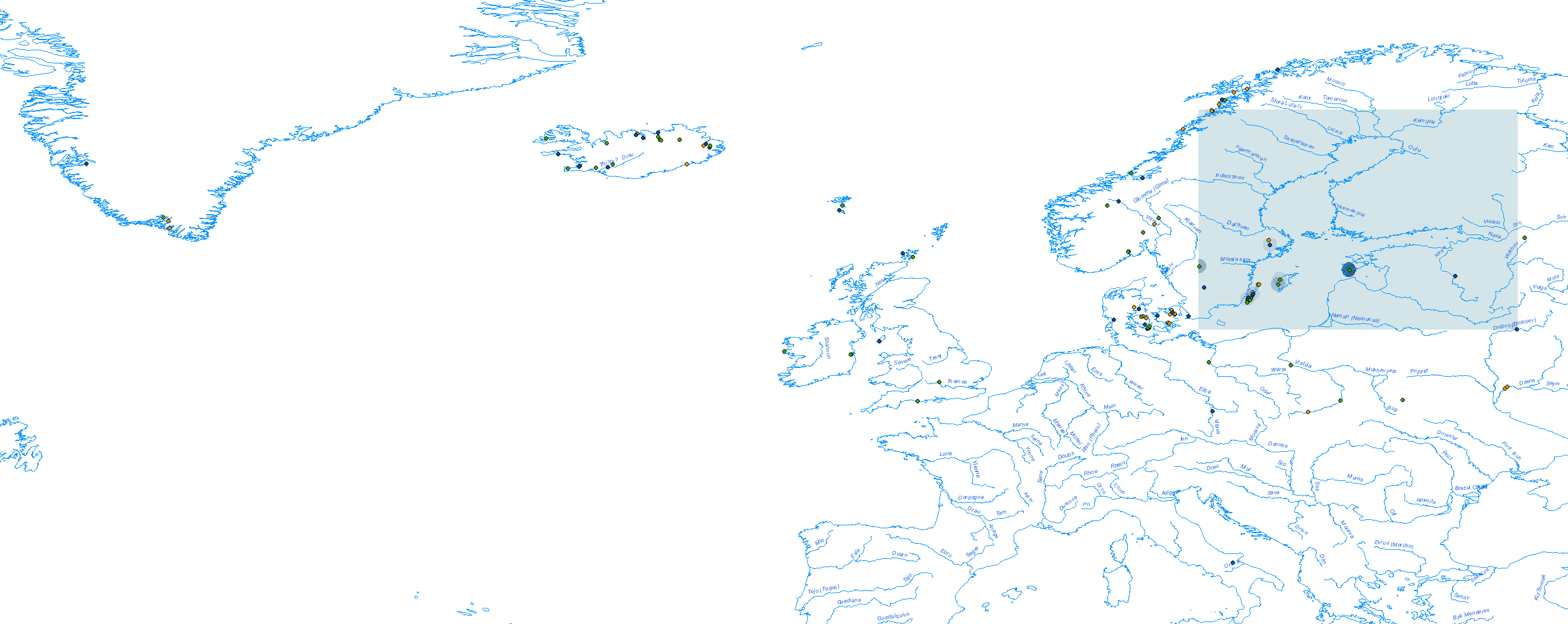

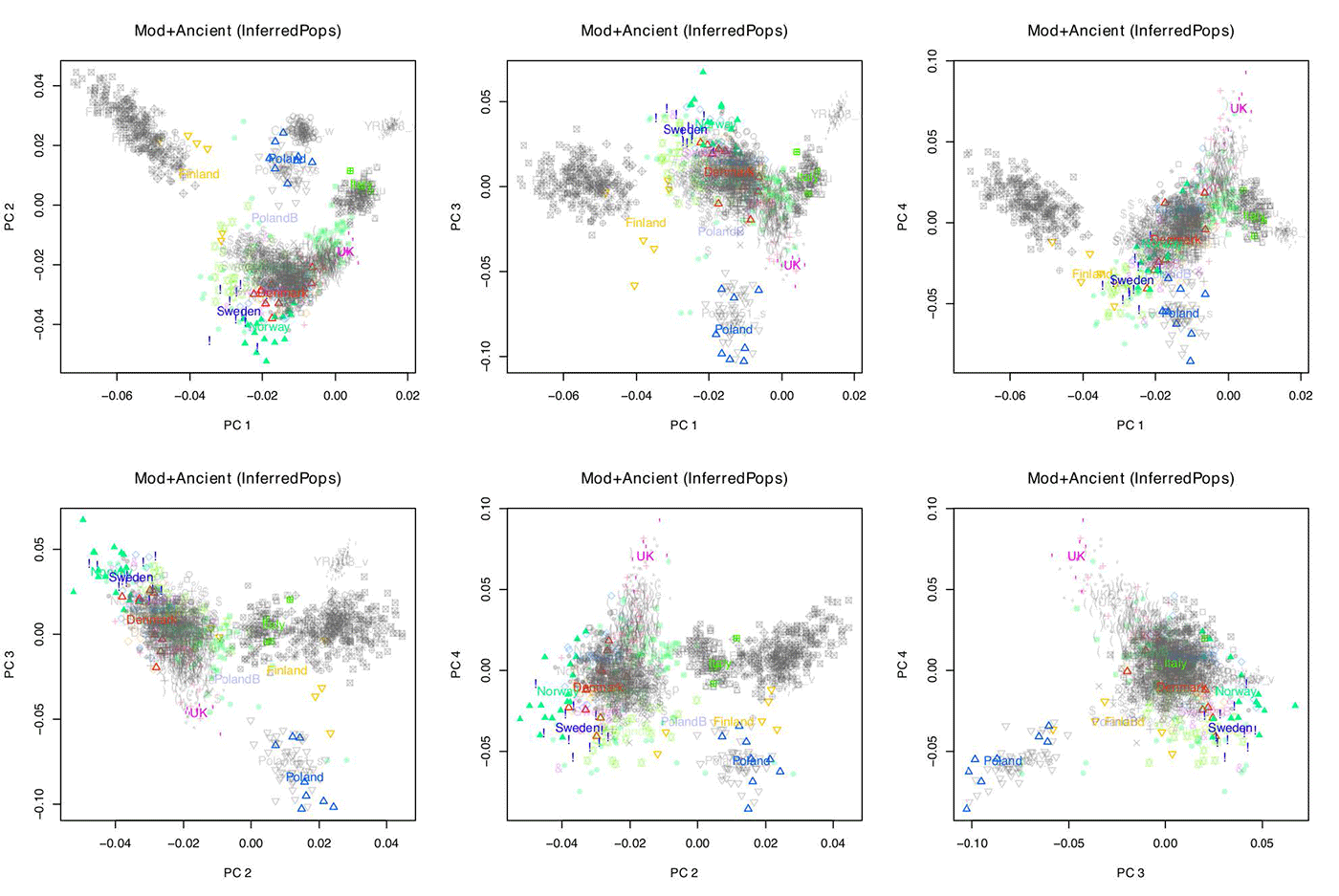

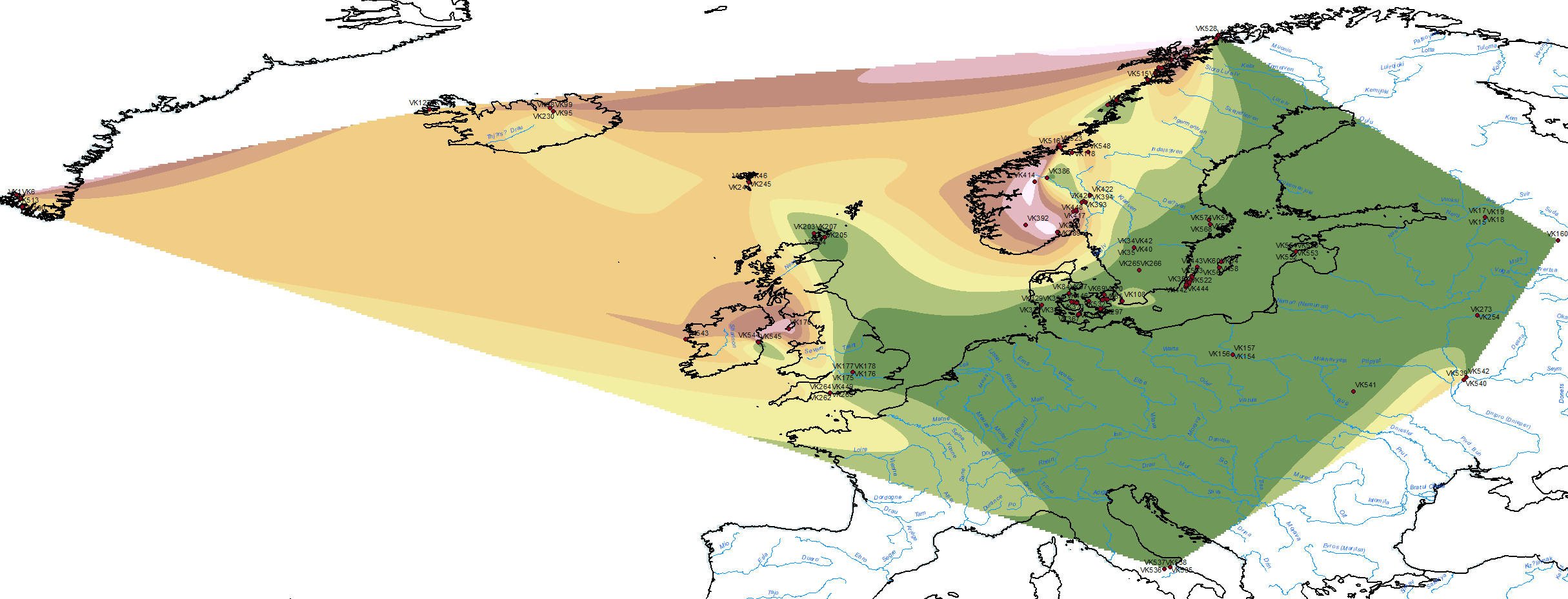

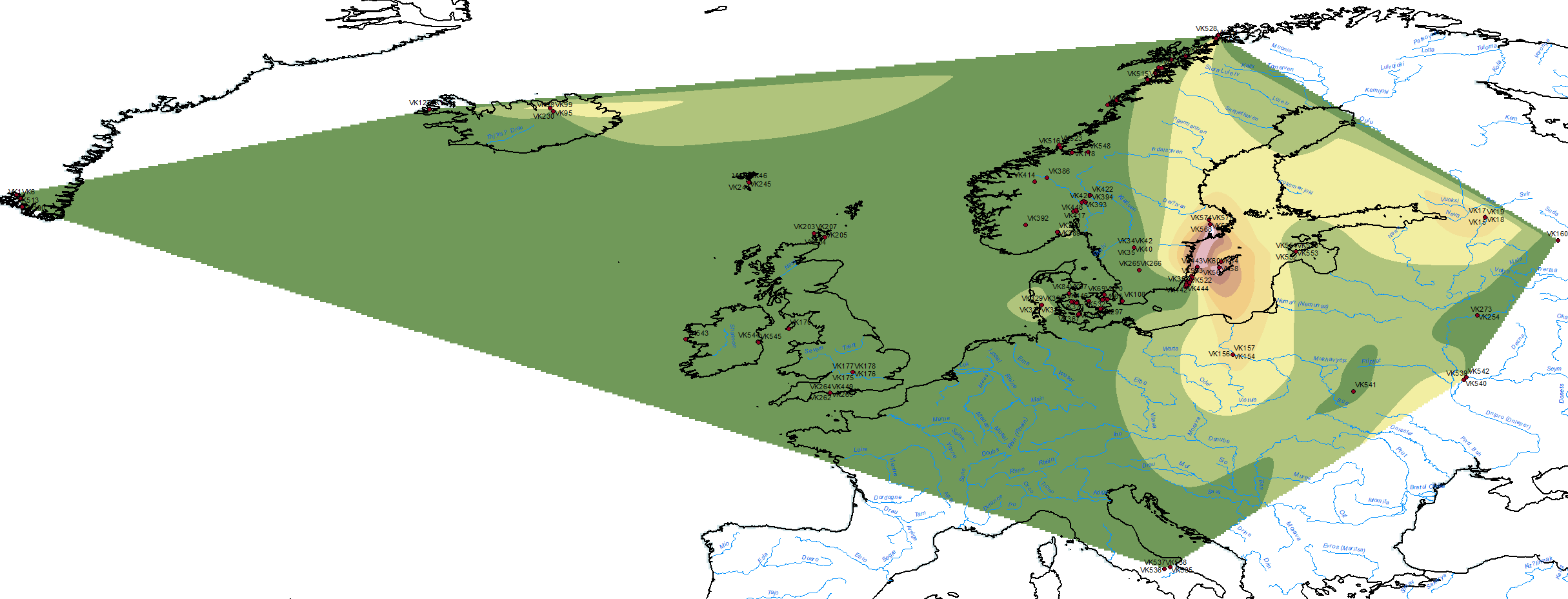

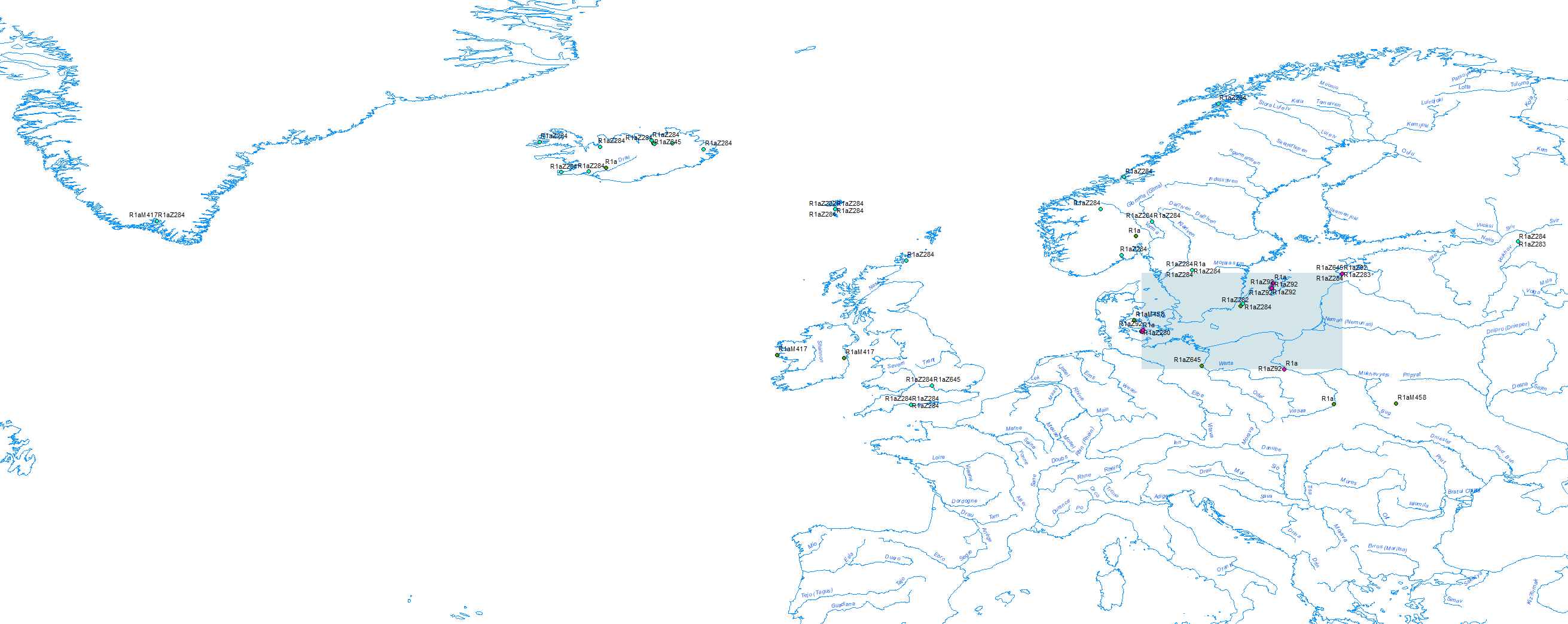

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.