Gotland’s Secret Language

One thing you’ll certainly want to try during your visit to Gotland is the islander’s ‘secret language’ – Gutnish. This language of Gotland is a dialect of Old Norse which was used by their Viking forefathers during Medieval times. Gutnish still survives and many people throughout the island speak it, though Gutnish is most commonly used on the southern parts of Gotland and the island of Faro.

Although Old Gutnish and Modern Gutnish are often mixed, the Gutnish which is used today derives from Old Gutnish which is indisputably considered a separate dialect and branch of the Old Norse language family. Linguists acknowledge Gutnish as a language, but for political or other reasons, it still hasn’t been officially recognized by the Swedish government. There is an ongoing effort and movement among Gotlanders to preserve their heritage and have their native tongue and language restored to official status and given the recognition it richly deserves.

The most famous surviving piece of Gutnish literature is the famous Gutasaga which is preserved and kept at the Swedish Royal Library in Stockholm where it can still be seen today. |Written around the year 1350, this manuscript is a saga covering the history of Gotland before its Christinization. A mixture of legend and verifiable historical facts, the saga begins with the story of how a mythical figure named Þieluar discovered Gotland. In the story Gotland remains underwater during the day and rises during the night. Þieluar breaks this spell by lighting a fire on the island.

Þielvar’s son Hafþi married a fair maiden named Hvitastjerna and they were the first to settle on the island. They had three children, Guti, Graipr and Gunfjaun. After their parents died the brothers divided Gotland into three parts, each taking one. This division of the island remained in place until 1747 and is still recognized by the church as the three deaneries. Guti remained the highest chieftain and gave his name to the land and its people. A Gotlander is called a ‘gute’, one of Guti’s native descendants. There are many good books available on the Gutasaga if you would like to read the full story.

Gutnish – ‘Old’ and ‘Modern’

Modern Gutnish is the native language of the Gotlandic people living on what some consider the mythological island of Gotland. It is Sweden’s largest island (3200sq km), and rests in the Baltic Sea off of Sweden’s southeast coast. Gutnish was both a spoken and written language until late medieval times. Today it exists as a spoken language,and though many of the Old Gutnish words are still used, to some degree it has become mixed with Swedish, Danish and German.

Whether the reasons are political, cultural or whatever they may be, it remains a highly controversial issue whether modern Gutnish is to be considered an independent language or a Scandinavian dialect. The Gotlanders are fiercely proud of their language and heritage and demand that their language be given the due recognition it deserves and be preserved for future generations. Unfortunately, so far the Swedish goverment has not officially recognized Gutnish as a language even though linguists have established that Old Gutnish, is indisputably a separate branch of the Old Norse language family. It has been unequivocally established that Old Gutnish shows sufficient differences from the Old East Norse dialect (also called Old Swedish or Old Danish) that is considered to be a separate language branch.

Today a somewhat modernized version of the Old Gutnish called Modern Gutnish is still spoken on the south-east parts of Gotland and on the island of Fårö which is just a few kilometers from Gotland’s northern coast. Gutnish exists in two variants, Mainland Gutnish an Faroymal on Fårö. The Faroymal is considered the more archaic of the two forms .The root Gut is identical to Goth, and it is often remarked that the language has similarities with the Gothic language. These similarities have led scholars such as Elias Wessén and Dietrich Hofmann to suggest that it is most closely related to Gothic.

Some features of Gutnish include the preservation of Old Norse diphthongs like ai in for instance stain, Swedish: sten, English stone and oy in for example doy, Swedish dö, English die. There is also a triphthong that exists in no other Norse languages: iau as in skiaute/skiauta, Swedish skjuta, English shoot.

Old Gutnish Word List

This is a list of common Old Gutnish Words, which is now added with Modern Gutnish (MG), and also Swedish (SW).

about – um (MG um; SW om)

after – iftir, ibtir, yptir, yftir, hebtir, ebtir, heftir (MG ettar/yttar; SW efter)

and – auc, ac, uc, aug, au, oc (MG u, ou; SW och)

ankle – ancul (MG ankul; SW ankel)

at – viþr (MG bei/vidur; SW vid/hos)

at home – haima (MG haime; SW hemma)

axe – yx – (MG yx; SW yxa)

be – vera – (MG vare; SW vara)

begin – byria –

between – millan (MG millum; SW mellan)

better – betr (MG betur; SW bättre)

both – baþi (MG bade; SW båda)

breast – briaust (MG braust; SW bröst)

brother – broþir (MG bródar/brór; SW broder/bror)

build – byggia (MG bygge; SW bygga)

butter – smier (MG smier; SW smör)

buy – caupa (MG kaupe/kaupa; SW köpa)

by – af (MG av; SW av)

can – cann (MG kann; SW kan)

cellar – kialeri (MG kellare; SW källare)

church – kirchia (MG kýrko; SW kyrka)

child – barn, ban (MG barn/ban; SW barn)

chimney – scurstain (MG Skurstain; SW skorsten)

come – cuma (MG kume; SW komma)

cut – skiara (MG skere; SW skära)

cut, chop – hagga, haga (MG hagge; SW hugga)

daughter – burna

death – dauþr (MG daud; SW död)

daughter – dotir, dotr (MG dótar; SW dotter)

die – doya (MG doy; SW dö)

do – giara, giera, kierua, kiara, kira, gera, kara (MG gere; SW göra)

door – dur (MG dur; SW dörr)

down – niþr (MG neir; SW ner)

each – huer

east – austr (MG austr; SW öster)

eye – auga (MG auge; SW öga)

either – huatki

early – arla (MG arle; SW arla)

eight – ata, atta (MG ate SW åtta)

eleven – alivu, elivu (MG elvo; SW elva)

either, or – eþa (MG ellar; SW eller)

elbow – alnbuga (MG alnbuge; SW armbåge)

fall – falda (MG falle; SW falla)

field – acr (MG akar; SW åker)

four – fiaura (MG feire; SW fyra)

fourteen – fiuhrtan (MG feurtan; SW fjorton)

fourty – fiauratighi (MG fýrti; SW fyrtio)

for, before – firi, firir, furir, furi, fyr (MG fýr, fýre; SW för, före)

fish – fisc (MG fisk; SW fisk)

fly – fliauga (MG flauge; SW flyga)

from – fran (MG fran; SW från)

forest – scogh (MG skóg; SW skog)

first – fyrst (MG fyrst; SW först)

gambling – dufl (MG dufl; SW spel)

goat – gait (MG gait; SW get)

good – goþr, koþr (m) (MG gódr; SW god)

god – guþ (MG gúd; SW gud)

ground, earth – iorþ (MG iord; SW jord)

have – hafa (MG ha; SW ha)

hold – halda (MG halde; SW hålla)

he – hann (MG hann; SW han)

him – hann (ack) (MG hann; SW han)

him – hanum (dat) (MG hann; SW honom)

hair – har (MG har; SW hår)

high – hau (f), haur(m) (MG haug f, haugr m; SW hög)

hang – hengia (MG henge; SW hänga)

help – hialpa, hialba (MG hialpe, SW hjälpa)

here – hiar, hier (MG hier; SW här)

hear – hoyra (MG hoyre; SW höra)

hit – sla (MG sla; SW slå)

house – hus (MG heus; SW hus)

I – iac, iec (MG iak, SW jag)

in – in (MG inn, SW in)

is – ir, ier, ar (MG ier/er; SW är)

judge – dyma (MG dýme; SW döma)

kill – drepa (MG drepe; SW döda)

later, then – siþan (MG seine/sidan; SW sedan)

‘like that’ – slicu (MG sleike; SW sådan)

language, speech – mal (MG mal; SW språk)

law – lagh (MG lag; SW lag)

lead – laiþa (MG laide; SW leda)

long – langr (m) (MG langr; lång)

live – lifa (MG live; SW leva)

more – mair (MG mair; SW mer)

month – manaþr (MG manad; SW månad)

man – maþr (MG mann; SW man)

milk – mialc, mielc (MG mialk; SW mjölk)

much – mikit (n) (MG mikit; SW mycket)

nothing – huerghi (MG varges; SW inget)

nine – niu (MG niu; SW nio)

now – nu (MG no; SW nu)

not – ai (MG ai; SW ej)

or – ellar, ella (MG ellar; SW eller)

on – a (MG pa, SW på)

one – ain (f) (MG ain; SW en)

our – uar, oar (m. sing. Nom.) (MG óre; SW vår)

offer – biauþa (MG biaude; SW bjuda)

over – yfir, ufir, ufr, ifir (MG yvar; SW över)

out of – yr (MG ýr; SW ur)

one – ann (m) (MG ann; SW en)

one – att (n) (MG att; SW ett)

people – fulc (MG folk; SW folk)

people – lyþr (MG lýd; SW folk)

pray – biþia (MG bide; SW be)

promise – lufa (MG luge; SW lova)

pole – stulpi (MG stolpe; SW stolpe)

pole – stang (MG stang; SW stång)

prayer – byn (MG byn; SW bön)

queen – drytning (MG drytning; SW drottning)

came- kuam, quam (MG kvam, kom; SW kom)

rise – raisa (MG raise; SW resa)

right – reth (MG rét; SW rätt)

shall – scal (MG skal; SW ska)

shoot – schiauta (MG skiaute; SW skjuta)

say – segia (MG sege; SW säga)

six – siahs, siex (MG sieks; SW sex)

soul – sial, salu (MG siel; SW själ)

seven – siau (MG siau; SW sju)

stop – lyfta, lykta (MG lykte; SW sluta)

she – han (MG ha; SW hon)

skin – skin (MG skin; SW skinn)

smith – smiþr (MG smid; SW smed)

so – so (MG so; SW så)

someone – nequar (MG nokun; SW någon)

spring – ladigh (MG ladig; SW vår)

stone – stain (MG stain; SW sten)

stand – standa, stanta (MG sta; SW stå)

steal – stiela (MG stiele; SW stjäla)

son – sun (MG sun; SW son)

south – suþr (MG sudr; SW söder)

sweet – syt (f) (MG sýt; SW söt)

take – taca (MG ta; SW ta)

that – et, at (MG at; SW att)

touch – royra

that – sum (MG sum; SW som)

trip – ferþ (MG ferd; SW färd)

that one – hin (f)

that one – hinn (m)

this – hitta, þitta (n)

to – til

ten – tiu

twenty – tiughu

twelve – tolf

two – tu (n)

two – tvair (m)

two – tvar (f)

them – þaim

they – þair (m)

there – þar

they – þar (f)

though – þau

they – þaun (n)

three – þriar (f)

three – þrir (m)

three – þry (n)

village – socn

we – vir, uir

week – wica

work – arfuþi

wedding – bryþlaupr

well – uel, vel

with – miþ, meþ

world – vereld

what – huat, hut

when – þa

widow – enkia

white – huit

woman – cuna

wound – sar

write – scrifa

yard – garþr, karþr

year – ar

young – ungr (m)

Examples of Modern Gutnish (‘The Garden of Love’ by William Blake) and Old Gutnish (Excerpt from the Gutasaga circa 1320)

Examples of Modern Gutnish (‘The Garden of Love’ by William Blake) and Old Gutnish (Excerpt from the Gutasaga circa 1320)

Modern Gutnish:

KERLAIKINS SKAVLGARD

Ja gikk til kerlaikins skavlgard

U sag va ja aldri hadde sét

A kýrko var der byggd

Der ja fýrr laikede pa de grýnu

U lukar til hissu kýrku var lukede

U ”Dú skalt inte”, ritet yvar duri

So ja vende mi til kerlaikins skavlgard

Sum so mange sýme blómar berde,

U ja sag hann fylldar me gravar

U gravstainar der blómar skulde vare

U prestar i svarte klédin, ganes síne rundar

U bindnes me napltynne, míne gledar u kéar

av William Blake (1757-1827)

Original English:

THE GARDEN OF LOVE

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut

,And Thou shalt not. writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns,

were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars, my joys & desires

by William Blake (1757-1827)

Old Gutnish (excerpt from the Gutasaga):

Þissi þieluar hafþi ann sun sum hit hafþi. En hafþa cuna hit huita stierna þaun tu bygþu fyrsti agutlandi fyrstu nat sum þaun saman suafu þa droymdi hennj draumbr. So sum þrir ormar warin slungnir saman j barmj hennar Oc þytti hennj sum þair scriþin yr barmi hennar. þinna draum segþi han firi hasþa bonda sinum hann riaþ dravm þinna so. Alt ir baugum bundit bo land al þitta warþa oc faum þria syni aiga. þaim gaf hann namn allum o fydum. guti al gutland aigha graipr al annar haita Oc gunfiaun þriþi. þair sciptu siþan gutlandi i þria þriþiunga. So at graipr þann elzti laut norþasta þriþiung oc guti miþal þriþiung En gunfiaun þann yngsti laut sunnarsta. siþan af þissum þrim aucaþis fulc j gutlandi som mikit um langan tima at land elptj þaim ai alla fyþa þa lutaþu þair bort af landi huert þriþia þiauþ so at alt sculdu þair aiga oc miþ sir bort hafa sum þair vfan iorþar attu.

English Translation:

This Thielvar had a son called Hafthi. And Hafthi’s wife was called Whitestar. Those two were the first to settle on Gotland. When they slept on the island for the first night, she dreamed that three snakes lay in her lap. She told this to Hafthi. He interpreted her dream and said: “Everything is bound with bangles, this island will be inhabited, and you will bear three sons.” Although, they were not yet born, he named them Guti, who would own the island, Graip and Gunfiaun. The sons divided the island into three regions, and Graip, who was the eldest, took the north, Guti the middle, and Gunfjaun, who was the youngest, took the southern third. After a long time, their descendants became so numerous that the island could not support all of them. They drew lots and every third islander had to leave. They could keep everything they owned but the land.

Preserving Our Past, Recording Our Present, Informing Our Future

Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan Int Society LLC

carruthersclan1@gmail.com

t is thought that Pictish kings may have dominated Dál Riada into the early 800s, with Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820) ( Carruthers DNA Marker ), perhaps placing his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riada from 811. It appears that the Scots-Gaels of Dál Riada became allies of the Picts against the Vikings. Amongst those killed during the earliest Viking invasions were the two most powerful men in the former kingdoms; the Pictish leader, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the leader of Dál Riada, Áed mac Boanta, who were both among the dead after the Vikings in 839 delivered a major defeat to the united forces of Picts and Scots-Gaels.

t is thought that Pictish kings may have dominated Dál Riada into the early 800s, with Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820) ( Carruthers DNA Marker ), perhaps placing his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riada from 811. It appears that the Scots-Gaels of Dál Riada became allies of the Picts against the Vikings. Amongst those killed during the earliest Viking invasions were the two most powerful men in the former kingdoms; the Pictish leader, Eógan mac Óengusa, and the leader of Dál Riada, Áed mac Boanta, who were both among the dead after the Vikings in 839 delivered a major defeat to the united forces of Picts and Scots-Gaels. This process culminated in the rise of Kenneth MacAlpin in the 840s. ( He carries the Carruthers DNA Marker ) Kenneth is known as the first combined King of Scots and Picts and died on the 13th February 858 from a tumour. Upon his death, Kenneth is recorded as being King of Picts, with the terms Alba and Scotland still not in use.

This process culminated in the rise of Kenneth MacAlpin in the 840s. ( He carries the Carruthers DNA Marker ) Kenneth is known as the first combined King of Scots and Picts and died on the 13th February 858 from a tumour. Upon his death, Kenneth is recorded as being King of Picts, with the terms Alba and Scotland still not in use.

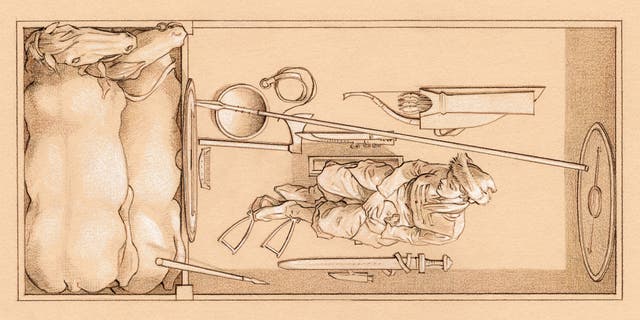

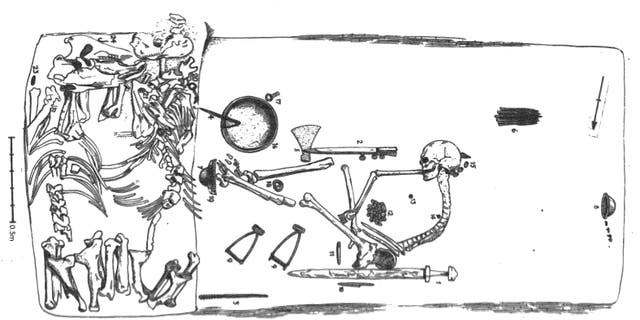

Over one hundred fifty hoards have been found from Viking Era Ireland, comprising mostly silver and bronze items. Along with the burial goods these folk were consigned to their graves with, and accidental losses now recovered, rich and diverse material remains provide vivid glimpses into the ways these mostly Norwegian raiders both changed and were changed by the Irish they settled amongst.

Over one hundred fifty hoards have been found from Viking Era Ireland, comprising mostly silver and bronze items. Along with the burial goods these folk were consigned to their graves with, and accidental losses now recovered, rich and diverse material remains provide vivid glimpses into the ways these mostly Norwegian raiders both changed and were changed by the Irish they settled amongst. The Viking incursion into Ireland meant a huge influx of silver was carried into the island – silver dirhams and Kufic coins from trade originating in Islamic lands, and masses of hack silver (broken bits of jewellery, coin fragments, slices cut from simple silver rods) brought as booty from pillaging targets along the shores of Frankland.

The Viking incursion into Ireland meant a huge influx of silver was carried into the island – silver dirhams and Kufic coins from trade originating in Islamic lands, and masses of hack silver (broken bits of jewellery, coin fragments, slices cut from simple silver rods) brought as booty from pillaging targets along the shores of Frankland. Irish workers in precious metals, already amongst the most highly skilled on Earth, where quick to adopt Scandinavian motifs into their work. Great penannular pins and brooches featuring bosses, thistles, kite-shaped pins, arm rings, and silver mesh work appeared for the first time in Ireland, adapted from Norse models.

Irish workers in precious metals, already amongst the most highly skilled on Earth, where quick to adopt Scandinavian motifs into their work. Great penannular pins and brooches featuring bosses, thistles, kite-shaped pins, arm rings, and silver mesh work appeared for the first time in Ireland, adapted from Norse models.

The anaerobic nature of Irish peat bogs has yielded many finds of organic materials in a high state of preservation. I had seen the stray 9th or 10th century shoe on display at Jorvik or the National Museums of Denmark or Sweden; here was a whole array of them, along with leather shoulder bags, water (or ale/wine) bags, and a jaw-dropping leather knife scabbard.

The anaerobic nature of Irish peat bogs has yielded many finds of organic materials in a high state of preservation. I had seen the stray 9th or 10th century shoe on display at Jorvik or the National Museums of Denmark or Sweden; here was a whole array of them, along with leather shoulder bags, water (or ale/wine) bags, and a jaw-dropping leather knife scabbard. Leather knife scabbard. Sublime example, thanks to preservation in peat.

Leather knife scabbard. Sublime example, thanks to preservation in peat.