THE VIKING SHIP

Most archaeological studies on Viking Age vessels focus on technological a aspects, on building and using the ships. While such questions are basic to the understanding of the ship itself it should be supplemented with the cognitive representations of those who used it, not only by sailing it but also as a metaphor and a symbol. There are a number of salient angles, e.g.anthropological, religious, pictorial, linguistic and literary, some of which have been treated before. This paper concentrates on three aspects: the horse and the ship, the significance of the sail and stories of portage in literature.

Introduction

The ship/boat is indeed at the origin of any cognitive aspect of the humans who use it, not only an extension of their corporeal means. This is a com-plex topic generally worthy of study. In this case pagan ideas may be as re-levant as Christian ones, since we are at a transitional period. A first impression could be that neither before nor afterwards had ships in Scandinavia been as important as during the Viking Age (e.g. in Wes-terdahl 1993). This would be based on the emblematic long ship shaping the post-mortem picture of the extensive journeys of the Viking Age. The significance of the boat to ordinary people is, therefore, underplayed. Judit Jesch put it in these words:

Although the words `viking´ and `ships´ so often seem to go together, ships were not necessarily more important to the Scandinavians in the Viking Age than in any other time in their history. The Viking Age may just have been when other nations became more keenly aware of Scandinavian nautical prowess” (Jesch 2001: 275).

In the literary aftermath of that heroic age the ship is always in focus. The following conclusion is from a review by the Swedish historian Erik Lönn- Christer Westerdahl

The Viking Ship in Your Mind: Some comments on its cognitive roles

by F.G. Bengtsson; Lönnroth 1961/1959/ the conclusion):

It is a magnificent testimony that the scalds offer on the spirit of the Viking Age. Butit is monotonous and its meaning is terrible. Behind the gorgeous imagery is a sea and a world as desolate as the empty eyes of the dragon heads, where the long ships rested as little as wind, waves and the rapaciousness of men. (my translation)

Who were the Vikings?

The Vikings, in the popular sense, were pirates, robbers and fought for payment as mercenaries in the service of lords, their own or foreign ones. There may have been a small streak of the tradesman in them, but that is may be just another side of the same rapacity, negotiation being simply a gesture of necessity. If you cannot rob you trade. In fact this transition iseven recorded in some historical sources (e.g. Arab sources on the Majjus ,translations in Birkeland 1954).

The reason why we study the Viking Age so intensely and thereby exaltit as being more interesting than other periods is also relevant. Another confrontational issue to address could be the reason why we call it the Vi-king Age. Presumably there were other salient historical processes during this period which has been bound up with the current concept Viking.

THE VIKING AGE

Of even greater interest is how this European connection enables us to contrast and capture the interplay between events played out on both the large and small stages. Curiously this line has perhaps been avoided by some scholars as it would show more effectively that the Viking Age itself was a rather isolated event, never to be repeated. The first step towards social progress in the continental sense, Europeanization, may, however, have started there and not earlier. In a sense the traditional direction of thinking about Vikings is logical and follows the research material at hand.

The sources at hand, historical, literary and archaeological, pinpoint exactly those strata in Nordic societies from which were recruited the “Vikings”. In other words we mean those possessing the resources to equip expeditions and crews, to colonize and to trade their surplus goods with others. They were certainly a minority in a repressive and highly hierarchical society. They are the personalactors (rather than agents) of the Viking Age in more than one sense.

But,then curiously enough, most of the authors, mostly Icelanders and Norwegians, who describe the situation during the Viking Age lived in another, different, age, the 12th-13th centuries. This text will not be about what we do have or what we do know, since there are so many authors who have treated the subject much more competently and also more in detail than I could ever do.

For example Judith Jesch has made a critical and very valuable study of scaldic and runic texts on ships and men during the late Viking Age (Jesch 2001).Certain elements in any assessment of the role of the ship are more self-evident than others. By way of their mastery of their ships and boats the Viking Age Norse were able to expand as “Vikings”. This means that the ship´s social significance, in that sense, was self-evident. But, perhaps less obviously, an array of symbolic aspects will show how society and social aspects were intertwined with human cognition. In fact they possibly give you a better measure of the degree of human significance of the ship, both as a metaphor and as a reality. This includes the metaphor of a ship-shape society, of the leding type and its probable ancestors (e.g. Varenius 1992: 27f; 1998: 36f; 2002: 254f; cf. also Lund 1996: 245f and passim). This is conducive to the potential application of the symbolic principle of pars- pro-toto, the part (stands) for the whole,´ displayed in texts, language,iconography including graffiti, and in ritualized behaviour of almost any detail of the ship: the keel, the stem (figures 1 and 2), the stern, the sail and the area around the mast, maybe even the weathervane, so typical of the Viking Age (Falk 1955 [1912]: 55; Westerdahl 1995: 46).

The general significance of vessels

That said, it must, however, be admitted that the ships are a special case ,simply because the culture of the North in general was maritime. Perhaps one should call it a maritime civilization rather than a maritime culture. Gunilla Larsson uses maritime ideology as an over-arching concept for the Central Swedish Iron Age (Larsson 2007). That realization does not stem only from the use of the warships but also from the already mentioned necessities. This part of society we only meet in the occasional mention of competition between chieftains or the exploitation of subjects. Maritime warfare is characterized by Björn Varenius as an organizing principle in the North from the Viking Age onward (Varenius 2002).There must be something particular about the Nordic ship: the ship-formed stone settings point to this. They are multiperiod, but common also during the Viking Age (Capelle 1986; 1995), sometimes even made of wood, e.g. in the boat-grave field of Valsgärde, Sweden (cf Arwidsson1942, 1954). There are numerous bog finds of vessels or parts of vessels(e.g. Shetelig/ johannessen 1929).

Some have undoubtedly been put there for preservation. Another probable explanation is that some were parsprototo offerings. There are ships carved on picture stones and on runic stones in various contexts (on context Andrén 1993; Crumlin-Pedersen 1991b: 183 fig 2; Lindquist 1941-42; Varenius 1992: 51f, 86f;1995; Imer 2003).The evidence of the ritual use of ships, especially in graves, burnt or unburnt, is striking (Müller-Wille 1970; 1974; 1995). Many questions arise, that are still fundamentally unaddressed and unanswered. They may concern, for example, the ship form as a grave. Is a symbolic transfer of vessel from water to land intended? Is it a question of the space of the vessel, or the proportions of the boat? Others relate to the plunder of these graves. What are the meanings of this haugbrót ? (e.g. Brendalsmo og Röthe1992). Why were not more burials with valuables (of any kind) plundered? Were these ships/containers, if they were thought of as that, considered more protective than other containers? We can be fairly sure that the grave-plunderers were not after the boats in the grave. Or were they? Is the burning of the deceased and his/her vessel a way of avoiding haugbrot ?

Such questions are relevant in this context, but they will not be treated fur-ther in this text.

The Horse and The Ship as Metaphors

By other authors the horse was recently supposed to be a kind of tool to help cross cognitive borders (Oma 2000; Opedal 2005: 78). Other scholars see the horse as a psychopomp , and some view the ship in the same light(esp. Ellmers 1986; 1995: 169f). Their twin-like appearance together, the counterparts in mythology probably being Sleipnir and Skiðblaðnir , on picture stones is possibly a good contemporary guide (figures 3a and 4; e.g.Crumlin-Pedersen 1995: 94; Ellmers 1995: 168 mentions Naglfarthe vessel of the dead).

The present author agrees with the idea that the horse and the ship are related in some way in the prehistoric pagan psyche, butt here is a further aspect to it. In my recent research, I refer to both as

liminal agents

(Westerdahl 2005a: 8f; 2005b: 26f). According to this perspective they appear in the maritime sphere to incarnate land and sea,respectively.

Figure 1. Graffiti on a loose deck plank from the Oseberg ship: a horsefight (cf figure 4) and a ship stem. After Shetelig 1917: 317.

It is suggested that the ethnohistorical material in maritime culture il-lustrates a structural opposition between sea and land. I have partly gathered this material myself recently by carrying out interviews in the field. This dual relationship is marked by the transition, the shore, which appears as a liminal area. The border between a social compulsion for different behaviour is drawn here. This compulsion is at work immediately on board the boat lying on the shore and from there out at sea. It is taboo to name things in the same way as on land.

This goes for things, living creatures, weather phenomena as well as place names. The best documentation and analysis of the Nordic area, including Estonia, was made by Solheim (1940). An earlier regional survey is, for example, Jakobsen´s striking dictionary from Shetland (1921). Normally this is nowadays, in its presumably fragmented state, referred to as “prejudice” and “superstition” .Perhaps it has rather been a consistent system of belief.

Figure 2. Gaming piece, reverse side, with ship stem and weathervane, 13th century AD,Lödöse, Sweden. Foto: Ola Erikson, Vänersborgs museum/Västarvet.

The shore area, or the area aligned with it, is the main location in the North for the remains of

a number of prehistoric ritual activities, including rock carvings, burial cairns

and in later, historical, times by stone mazes.

A probable inference would be that this recurrent dual cognitive set, sea to land, was present also in prehistory. One of several cognitive equivalents to the abstract division between sea and land appear to be the horse and ship in agrarian cultures. Both are strongly represented as symbols in depictions on rock carvings and standing stones. The predecessors in hunting and gathering groups would have applied the boats, sea mammals, seals and whales, and above all the elk

Figure 3b. The bracing hanfot system of the ship depiction on a picture stone from Smiss I in Stenkyrka parish, Gotland. Probably the deceased person to which the erection of the stone is devoted is sitting at the stern. It seems that all crew members are holding the ends of the braces. After Nylén & Lamm 1988: 109 (figure 5, note the ship) and to some extent the stag, in the same cognitive roles.

Fragments of other ethnohistorical material reflect related conceptions.This cosmology is not the only possible one. Symbols are notoriously polysemic, or polyvocal, i.e. they represent different cognitive factors at different times and to different people. In this case the solar cosmology (Kaul 1998; Kaul 2004) of the Bronze Age certainly belongs to the ruling class, coloured as it is by foreign prestige-laden elements, but the under-lying magic and ritual modelled on the liminal shore and its two elementsis presumably indigenous, with deep roots in the past. The first ship formed graves appear

before the Bronze Age.

It could even be maintained that the subsequent behaviour was in itself an expression of a counter-ideology of the underdog maritime people to the ruling powers on land. The dual structure unfolds in two-sided representations of fundamental opposites in human culture, between which interaction strengthens their application: such as gender, male to female, fundamentals, life to death, even colours such as black to white.

In Gaelic cosmology we find Tír na nÓg, `the land of Youth,´ as the realm of death out in the WesternSea (Rolleston 2004: 105 and passim).

It is to be observed that fairly recent folklore identifies precisely these opposites are associated with sea and land, respectively. The Mermaid is the mistress of the sea; black is the colour of the land and must not appear on board. Between them transfer is most obviously made in the case of life to death by the main liminal agents in the Bronze and Iron Age, the ship and the horse. The ritual or ceremonial transfer of the ship and its form to land has, so far, no such direct archaeological parallel with a transfer of the horse to the sea, except in the striking application of horse´s heads to ships brow.

This is seen most clearly in ship depictions of the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (figure 6). Perhaps this is the background for the problematic names of the legendary Saxon invaders of Britain,

Hengist (stallion) and his brother Horsa (horse) (Ward 1949; Turville-Petre 1956). Weshould remember from the saga literature the defiant act of Egil Skalla-grimsson when he puts a horse head on a pole as a nid stong turned towards land, explicitly to scare the land vættir

(Egils Saga 1933: 171f). Very likely, this is an expression of age-old magic. But in recent folklore the naming of land forms such as (the) Horse, in different languages, is also a strong factor indicating still largely unknown and unexplored fields (Beck 1973: 119f).

Hydroliminality, the extension of the possible, and indeed probable, significance of the sea to all forms of water is an intriguing problem to be discussed further. There are also problems of interpretation to be analysed inconnection with the cognitive function of, for example,

the horse-fight (fig-ures 1 and 4). Perhaps is best to suggest at this stage that the cosmological universe was multi-layered, and that the dual components ultimately were also individualized more or less as divine, with accompanying complex rituals expressing myth and rituals explained by myths.

Human beings seemingly interceded in the same way between opposites, passed the border, and could be considered as liminal agents. Normally we refer to them as shamans or wizards, but other categories may also be considered in this light. It is interesting to note that two of themost infamous wizard groups at sea were the Finns and the Saamis. Thenotoriety in this regard of the Finns was recorded in Europe already at thebeginning of the 13th

century (Saint Olaf´s Saga, in Heimskringla 1964:VIII: 121; De Anna 1992; Toivanen 1993; Toivanen 1995). The Saamisemerged as wizards at least as early in Nordic texts. In such a capacity they are mentioned possibly before 1200 (Historia Norvegie 2003: IV, 59ff).The reason may be that they were both, in popular representations, very much anchored to the land, being inland peoples and belonging to moun-tains and forests. This idea was and is still incorrect but still alive. But thiscould have been the reason why they were thought to be stronger at sea than all other people.

Figure 7. The Roman ship carved in a cattle bone thrown in the river Weser, Germany,dated to the 5

th

century AD. Legible runes of the 24-type variety tell us (probably) that “we are coaxing them (the Romans?) here.” After Pieper 1989, Abb. 29: 117, remade by the author: the object is rounded (a bone) and the figure unites three of the illustrated four sides

The Sail as metaphor

The present state of archaeological research tells us that the sail was adop-ted first during the Viking Age in the North. In 1995 I published a texton the possible consequences of this apparent fact (Westerdahl 1995).Some further comments will be made in retrospect. Especially interesting was the question as to why the sail was adopted so late and seemingly he-sitantly by the peoples of the North (not only North Germanic groups).The technical advantages of sail to oar propulsion appears so obvious to our time and our context. The North was well aware of the existence of the sail, even its technicalities, among the Romans (figure 7).In 1995 I suggested three contextual ideas as explanations, two were functional and made mainly military sense: the first maintained that the kind of society under consideration was still certainly very much a martial one, but its basis was surprise raids where you did not want to be seen in advance. A sail would spoil stealth. The second was the apparent need for coordination in such raids, which you could not expect in a fleet driven by fickle winds (figure 8). Rowing time could nearly always be computed, especially provided with a high degree of technical sophistication in the process of rowing, something that can be safely assumed for this period. The transition from the other method of manual propulsion, paddling, may have taken place a thousand year searlier, since it is difficult to find an adequate ancient word for `paddling´and `paddle´ in the Scandinavian languages (Sandström 2015).The third was a strong social and cognitive conservatism: to be part of a particular rowing crew, a comitatus-type segment of a fundamentally rowing society owing allegiance to a chieftain; one man, one oar, one row-lock. In the ships of Nydam c. AD 400 it appears that all rowlocks are individually made, perhaps even the oars (generally Rieck 1995; Rieck 2002: 76, 77, 80; the standard work Rieck et al. 2013).

Maybe the depiction of the first sails on some Gotlandic picture stones of a

hanfot system of braces (figure 3b) in the hands of almost all the members of the crew is a nostalgic remembrance of rowing as a social act?I suggested further in my paper that during the Viking Age, the sought-for legitimacy of the new royal rulers paved the way for a new paradigm

where the leaders wanted to be seen,

where the display of large fleets was a prerequisite for intimidation and enforced domination of a totally differ-ent kind than what came out of former hit-and-run (row) tactics.

Two parts to put together:

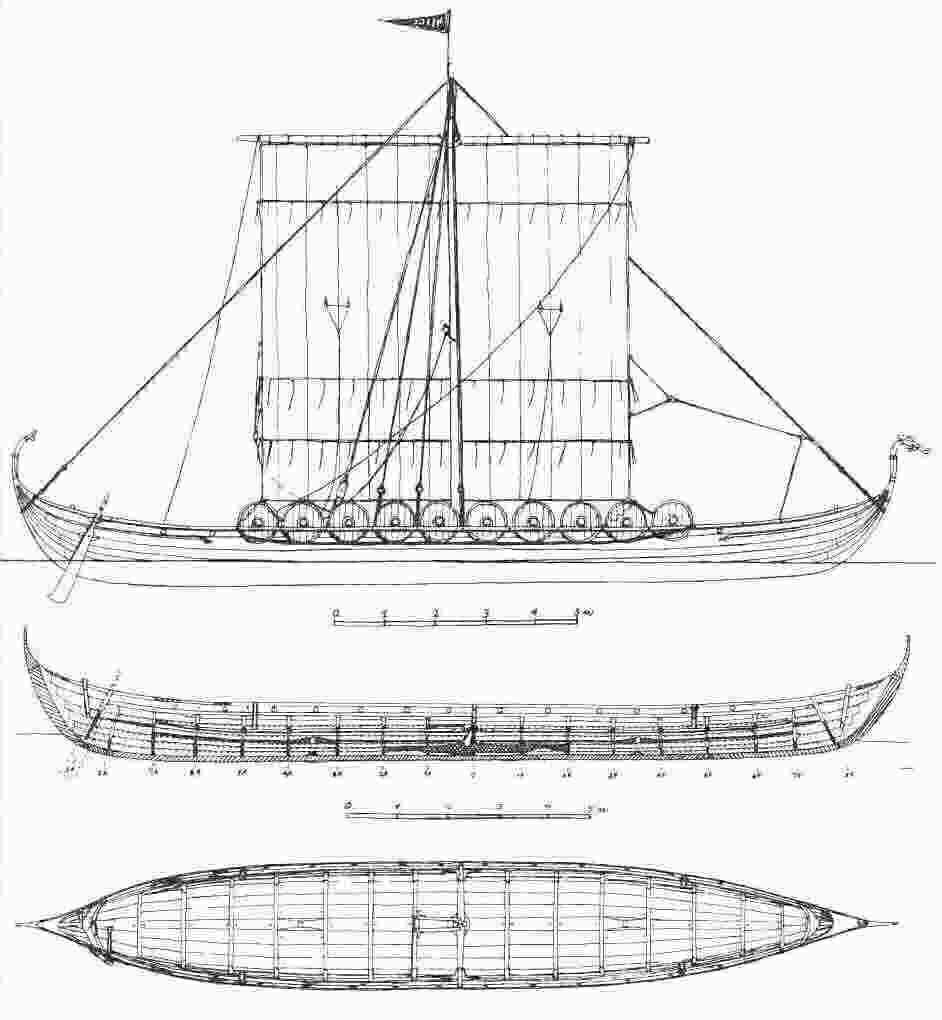

Contrasting rowing (Nydam) and sailing ships (Gok- stad). Drawing: Sune Villum- Nielsen. After Westerdahl 1995: 44-45, Fig. 4.

The metaphor of rowing must, however, have been strong even in the days of sail. In much later medieval provincial laws, attempting to implement efficient taxation, a metaphorical rowing ship society is conjured upas its basis, very probably petrified and archaized, but still functional as such. We know that ships, basically meant to be rowed, were in fact still used as

leding vessels into the 14th and 15th centuries in some cases. Arable lands in the Nordic countries were divided by the kingdoms into units corresponding to the “archaic” principle of one man, one oar, one bench.

Hå/ hamna (and equivalents) which literally meant rowlock and fastening for the oar in the ledung of the medieval provincial laws, was the smallest unit, a couple of farmsteads, sometimes a hamlet. This complex has resulted in an extensive literature (for references, see Lund 1996; 1997;2002; Varenius 2002; Sandström 2015).

But this metaphor need not hark back entirely to the period before the Viking Age. Crumlin-Pedersen(1997b: 189f) has pointed out that the drastic widening of ship beams to provide stability in the first period of the sail was followed by a return to pre-Viking long and slender warships (in combination with sails) precisely to maximize the effect of rowing in the last period of the Viking Age (10th-11th centuries).

Variations of size and function are pointed out as well by the same author (Crumlin-Pedersen 2002).In a sailing ship the crew is inactive, sails propelling the ships. The winds are governed by superior powers rather than men. Only kings would thrive in such a system. And in fact they do, according to the imagery of royal court poetry (e.g. Malmros 2002; 2010). Only they would depend on chance and a divine intervention, or on Grace from the Lord himself. The last major ship find without any arrangement for a mast are the sacrificial Kvalsund boats of West Norway, cal 14C AD 690, probably indi-cating their use well into the 8th century. A later find, but obviously from the last part of the same century is the burial ship of Storhaug, Karmøy, Rogaland, but still without a mast arrangement (Opedal 1998: 40f; fore-seen by Christensen 1998; dating in Bonde and Stylegar 2009). The first find with a mast-step, although rather a weak one, is the famous burial ship of Oseberg of Vestfold, South-eastern Norway, dendrochronologically dated to AD 815-820, but deposited AD 834. The burial chambers of the ship finds of Oseberg, Gokstad and Tune were dated in 1993(Bonde and Christensen 1993a & b). All agree that the oldest depictions of sailing ships in the North are thoseof the Gotlandic picture stones (a late group of them: figure 3a and 3b).Less known abroad seems, irritatingly, to be that Varenius’ (1992: 80ff) re-dating of the scheme once offered by Lindquist (1941-42, part I: 108ff)has been confirmed and made even younger by way of research by Imer(2003). None of these works are available in English, except relevant sum-maries.

The groups of Gotlandic picture stones with sails all belong to the Viking Age

; whether it started AD 750 or AD 800 is still an open question. But it is still quite common in literature that the alleged datings of thesesailing ships and boats still bring us back to the 6th and 7th centuries AD(Thier 2003: 184 still cites Lindqvist 1941-42).Thus, despite efforts to put the innovation back in time among theNorth Germanic peoples this seems to be the generally accepted opinion.I still stand by my explanations. However, some of my other ideas in thearticle (1995: 47f) on the use of the sail as a medium for symbols and he-raldic figures have faded into relative obscurity, although still applicable in the case of the cross on the sail of the Sparlösa stone (figure 10; Wester-dahl 1996; 2011:33f). On the Carolingian background and function of this cross see Horstmann 1971. But it is obvious that the Gotlandic de-pictions of sails (figure 3a and 3b) contain information of a symbolic char-acter from the very beginning. If they connote the divine ship – parallelin this context to the divine horse Sleipnir –that ship may indeed bethought of as Skiðblaðnir, always provided with a fair wind (Westerdahl1995: 46).Critics have approached the dating of the first Nordic sail by archaeo-logy in different ways.

Sailing enthusiasts of modern times are sceptical(e.g.Gifford & Gifford 1999 on Saxon ships). The Sutton Hooship in the 7th century, they claim, could have been sailed. Timm Weski thinks thatthe journeys of the Saxon invaders of Britain could not reasonably have been made only by rowing, despite the testimony of Procopius (c AD 550;Prokop 1978: 870f). He points to a very early find: a hole in a rib in thestem part of the Lecker Au find of Dithmarschen in Northern Germany,a log boat, 14C 1790 BP=ca AD 160, a long (c 13,5 m) and slender construction (Weski 1998: 68). However, the general character of this findand its context makes it rather improbable. A step for a hauling pole in these shallow and narrow canals seems fairly appropriate. Other voices point to alleged Saxon sailing mentioned during the 5th and 6th centuries AD (Haywood 1991: 62f; cf Thier 2003: 184). But these details are found only in a few (three) fairly obscure texts, and only one seems at all possible. The others appear to use such ambiguous meanings as could be applied to sailing as a general term for `travelling at sea´ or`using a boat´. Another possible way of approach would be the dating of the appea-rance of a mast stone in the middle of a stone setting of a ship. Such casesare known, but appear to be at least Late Iron Age or rather Viking Age(Capelle 1986: 29, Abb. 18, p 31; on Bronze Age ship settings in Capelle1995). However, the objection weighs heavily, I think, that a symbolicship in the ground might have had cosmological connotations where thecentre of “vessel” space could be marked for other reasons.The Irish hermits using hide boats, curraghs, could have been, in fact,the first to use sail in the area (on the undated Broighter model see Farrell and Penney 1975; see Marcus 1980 part I: 3ff on these pioneers).Maybe their type of large hide boats were easier to adapt to sailing thanthe existing types of slender, wooden rowing boats? An informed philolo-gical discussion on the introduction of the Germanic word sail has been provided by Katrin Thier (2003: 187) where she points to a possible transfer from Celtic-speaking areas along the Rhine. But nothing new on the dating of the sail in the North has come out of this. The state of the present research remains.

Thus, any human conception of ships must have been heavily influenced by the introduction of the sail in the period AD 750-820. It could be rewarding to look at the re-action of by-standers to this development, which might have been fairly rapid. In the North, Saamis recorded Nordic ships in recently found rock carvings in inland mountains in Northern Sweden (Mulk and Bayliss Smith 2006). These motives (figure 9) are, so far, unique in their setting,and it has been suggested by me that they belong to an early part of the Viking Age (cf the ship of the Sparlösa runic stone of Västergötland datedc. 800, figure 10) (Westerdahl 1996; 2011: 33f) and thus that the first sail-ing ships truly were thought remarkable by the Saamis. The coastal Saamis were experienced in boat culture long before that. The magic use of ship depictions may have a background not only in the Saami cultural world on its own, but also in the attitude of the Norse towards them: their aura of (inland) wizards at sea (above and Westerdahl 2005: 17ff).The Viking Age sails were made of wool (Andersen and Andersen 1989; Andersen, Milland and Myhre 1989; Andersson 2007; Möller-Wiering 2003, 2007, Rast-Eicher and Bender Jørgensen 2013 on the use of woolin the European Bronze and Iron Age; cf Waetzoldt 2007 on the material for other purposes in Mesopotamia). It is obvious that a prerequisite for sailing was a large-scale surplus production of wool. The technology of

this production and the refinement of such cloth was indeed not created overnight. It is probable that the original coastal heather landscapes of western Scandinavia and other parts of northern Europe – the grazing lands of sheep – are a result of this. Some 14C datings of the first burning of the coastal heaths in Western Norway point to the middle of the 8th century AD (Bender Jørgensen 2005; 2012; Cooke & Christiansen 2003;Zagal-Mach 2013).

The immediate candidates for an innovation from the outside are the Frisian sailing merchants (Lebecq 1983: 177ff). Their appearance coincides with the rise of the first preurban sites in the North, i.e. Ribe c. AD710-20 and Birka, Hedeby and Kaupang following suit rapidly. On theother hand the sailing arrangements of the North – keelson with mast step –and the terminology of the Northerners were accepted as loan words elsewhere in Western Europe, as far as we know in a different way as compared to what we know about Frisian ships (though very little is known).I

f so, the idea may have been received from Frisians but the actual shaping of it was at least partly a native one. It is probably less likely that sails of the river boats of the East were taken over by Scandinavians. But of course the possibility exists of a two-way process (Larsson 2000; 2007: 97ff on possible Byzantine mushroom-shape sail forms on early Gotlandic picture stones with Russian parallels).

Even though the production of sails took some time to be efficient for large fleets the time for sails may have been ripe in another way: it has been noted that both of the Kvalsund finds, up to now almost the last known rowing ships/boats, had developed a Nordic T-formed keel, which is normally considered an important step towards reducing leeway (She-telig and Johannessen 1929; figure 11).The kind of sail adopted was the square sail. What it looked like in the beginning and the veracity of iconographic sources has been a matter of debate in recent years (Kastholm 2009a; 2009b; Crumlin-Pedersen 2010).In northern Europe the square sail on one mast would reign supreme intothe Late Middle Ages. To put this into perspective: in the (Eastern) Medi-terranean the square sail had existed since at least the 3rd millennium BC.Then the lateen sail was adopted a little earlier than the square sail in theNorth. During the 7th century AD it seems to have been used in Egypt(Basch 1997). But it is interesting to note that it took at least 600 years before the Mediterranean maritime cultures reintroduced the square sailin earnest, this time together with other innovations from the Northerncog, such as the stern rudder.

Figure10. The Sparlösa picture stone, carved on all four sides, also with an extensive runic inscription, the ship and rider scene with a house on top resemble the structure of severalGotlandic stones. The archaeological dating is c AD 800. Note the cross on the sail, and the weathervane, cf fig 5. Photo: the author 1999.

Portage as a metaphor

I have chosen to treat yet another interesting metaphoric issue, partly based on my own specialties. It is not specifically related to the Viking Age, but is documented by medieval records referring to that period. The phenomenon of portage is still of current interest to me, since my conference on this theme in 2004 (Westerdahl (ed.) 2006a). Portages are mentioned several times in medieval sources, mostly in connection with military tactics. Place names indicating transport over land, sometimes explicitly with boats carried or dragged are prolific. An everyday practice certainly existed into our own times with smaller vessels, both at the coastand inland (Westerdahl 2006b: 44). It is even possible that there has been an ancient ritual or mythological side to it, to judge from depictions of a man carrying a boat in a number of rock carvings (figure 6). The transfer of a boat or ship form to land is, as mentioned above, not just a metaphor but was a living reality in the past: it occurs in ship graves, offerings, ship settings and rock carvings. As the obligatory ancestral introduction to the Orkneyinga saga, (Ork-neyinga saga, transl. Pálsson & Edwards 1978: 23-26) we meet a medie-val romance of the fornaldar saga type. Two brothers, called Nor & Gor, descended from a primeval king of Finland called Fornjot, set out to find their sister, who has disappeared. Nor and Gor appear to be entirely invented rhyming names, Nor (maybe Gor as well?) presumably being part of the literary etymology for Norvegr, Norway. They explore the whole of the North. Gor goes south by ship, searching the islands down to Denmark. Nor walks across the watershed of Scandinavia, the

Kilir, to Norway. Now they divide the peninsula. “Nor was to have all the mainland and Gor the islands, wherever a ship with a fixed rudder could be sailed between them and the mainland.” (Orkneyinga saga, 1978: 25). Gor thus became a Sea King and begat two aggressive Viking type sons. One of them was Beiti, who came up with a ruse based on the agreement:

Beiti sailed for plunder up Trondheim Fjord. He used to anchor his ships at a place called Beitstad, or Beitstadfjord. He had one of his ships hauled over from Beitstadnorth across Namdalseid to Namsen on the far side, with Gor sitting aft, his hand on the tiller. So he laid claim to all the land lying to port, a sizeable area with many settlement. (Orkneyinga saga 1978: 26)

This has indeed a lot of the ingredients of a lygisaga (lie saga). But as Bruce

Lincoln (1995) demonstrates by way of Gautrek´s and Rolf´s saga, there is a medieval cognitive world to be explored in the structures of these sagas. The land that is connected to the mainland by the long “portage” valley of Namdalseid would refer to the peninsula of Fosen, a fairly large and to a certain extent well-settled area in the Iron Age.

This resembles the Scottish adventures of Magnus Barefot (figure 12).He uses the same ruse (but no agreement is mentioned there). According to the Heimskringla (here in English translation, Snorri Sturluson 1961[1930]), using sources which are close to the event, such as the Morkinskinnams c AD 1210, Magnus sailed west from Norway with a strong fleet in AD 1098. He went to Orkney and further south, conquering Anglesey after successfully fighting “Breton” (of course rather Norman: earls, those of Chester and Shrewsbury) earls in the Menai strait:

Now when King Magnus came north to Kintire, he had a skiff drawn over the neckat Kintire and shipped the rudder of it. The king himself sat in the stern-sheets, and held the tiller; and thus he appropriated to himself the land that lay on the larboard side. Kintire is a great district, better than the best of the southern Isles of the Hebrides, excepting Man; and there is a small neck of land between it and the mainland of Scotland, over which long-ships are often drawn. (Saga of Magnus Barefoot, SnorriSturluson 1961: 264.)

*** The Carruthers CTS DNA matched with King Magnus. Eric II, King of Norway, Magnus, married Isobel , Queen consort of Norway, de Bruce, on 25 Sept 1293. Isabel du Bruce died 13 Apr 1358, Bergen Hordland, Norway. Margaret, King consort of Scotland, Dunkeld also married Eric II. I bring this up because King Magnus might have gone to Scotland many times. ***

The peninsula of Kintyre has one of the most well-known Tarbert(appx `portage´) sites of Scotland (MacCullough 2000; Phillips 2004; 2006).But it seems that the gesture of king Magnus, if it really took place like this, was an empty one. The king of Scots did not alienate Kintyre and there are virtually no signs of Norse settlement on the peninsula (Cheape1984: 213, 217). But even if the event was without actual political importance at the time it obviously had symbolic implications, as a prophecy for the future (below).In the case of Kintyre it might be that the domination of Kintyre, often understood or referred to as an island rather than as a peninsula, was a metaphor for the dominance of the entire island world of Scotland? Thusas Gor would have it, the Norwegian islands.

Already in 1796 the Scottish historian David MacPherson indicated a direct connection with another portage to sustain a similar claim, that made by King Robert Bruce in or around the year AD 1315. Bruce had then succeeded in beating back the English at the famous battle of Ban-nockburn close to Stirling: “The tradition of this event probably produ-ced the prophecy, that the isles should be subdued by him, who should sail

across the Tarbat; to fulfil which king Robert I had his vessels with sails hoisted dragged over into the western loch.”(i.e. the bay of the sea; Mac-Pherson quoted after Cheape 1984: 209). The prophecy was that of John Barbour, the author of the patriotic epic The Bruce (finished c AD 1375;Cheape 1984: 214). According to this poem Bruce ordered sails to be seton his galleys (plural in contrast to the other cases) to take advantage of a good wind blowing in the right direction. A striking local tradition adds that one ship was even blown off course and foundered at a place called in Gaelic Lag na Luinge `The Hollow of the Ship´, Cheape 1984: 215).

There are several interesting reflections to be made. The point is made above in the quotation that the ship in both Norse cases has to be used in a functional way, with a fixed rudder. The kings are holding the rudder dur-ing the haul. A side-rudder that is still in its functional position requiressome draught in this case in the air. The Bruce story uses sails and transports more or less a whole fleet over land. This may be understood as a symbolic reflection of the truly royal claim of the past. Another fleeting reflection must be made on the watershed in the first,case of the Orkneyinga saga.

This watershed is called Kilir, the Keel(s),which is still Kjølen (Kölen) in Norwegian or Swedish. It means that this mountain ridge (and several others, in fact; cf Lindberg 1941) could have been likened in common cognition to an upturned boat´s keel At least it must be asked whether all these stories mean that by inference any vessel in a metaphorical sense could mark a border-line. At leastthe portage appears as a metaphor, for the claims of a sea king in the three cases of Namdalseid and Kintyre. Obviously a new territorial border can be demarcated by a moving vessel across a portage/valley.

By definition this is found at the lowest land.However, the watershed Kilir runs along the length of the Scandinavian Peninsula, following the exact opposite, the protruding and highest land. An additional difference between these two would be that in most cases the portages run right through the land and across its watersheds. On the other hand, a portage could be a watershed, sometimes in a transferred sense.The notion of a boat being used to demarcate a border in a much smaller context is proposed by Gunilla Larsson in her recent thesis (Larsson2007: 298, 359). In the early Viking Age towns the area of the specialtownship jurisdiction had to be marked.

The low rampart or the shallow ditch that we know from Birka or Ribe would reasonably serve no effi-cient defence purposes. They would rather demarcate the “lawful” area of the town. The rampart of Hedeby is of course more substantial, but maybe because it was more or less a part of the Danevirke defence wall system ,built before the Viking Age. In the symbolic ramparts of Birka were in fact found three unburnt boats. Two had no connection with a grave, but one may have. They could have been put there as fill, as if they were actually forming the barriers of sailing routes, where they certainly served a defensive purpose (which seemingly they did not in this diminutive bank). However, these boat shad been placed in the rampart almost complete and not in pieces, which would have been more functional if they were only complements to the earth. Larsson finds that it is quite plausible that the boats had a particular significance in this border, which perhaps only could be crossed with a payment/customs due. In her text, Larsson mentions other markings of borders, of sanctity, territory etc (Larsson 2007: 298, 359). An even less empirically based idea is that of a certain sequential building structure of the vessel as describing a border. Mary Helms finds that constructing the shell, or planking first, which is the only procedure known in prehistory, e.g. in Bronze Age Britain or in the Nordic area much later, may express the basic integrity of the shell of the boat as a boundary form in and of itself (Helms 2009).On the contrary the Romano-Celtic (Gallo-Roman) boats were built skeleton, i.e. frame, first. This is an early and isolated instance of what during the later Middle Ages and Early Modern Times will be dominant:

These contrasting approaches to boatbuilding are not trivial differences. They seem to imply two fundamentally different perspectives regarding basic principles of construction that may well go beyond boat building per se to express contrasts in fundamental principles relative to the ordering of space and experience, including even landscape organization and cosmic construction (such as enclosures, henges etc). The Romano-Celtic boat seems to signify an `internal´ mode of building in which inter-ior structural forms are primary, while the Bronze Age sewn plank boat gives primacy to creation of a barrier that will separate and distinguish between interior space and exterior space, that which is within from that which is without. (Helms 2009: 154)

A particular jurisdiction on board ship was known in Nordic provinciallaws in connection with the leding. There are many markings of “extra-territoriality” for trading and shipping in societies similar to that of the Viking Age (e.g. Westerdahl 2003).In this case the trading settlers may also have secured divine sanction for breach of the market peace. Thus her interpretation could touch on Crumlin-Pedersen´s idea on the tradition of the ship as an icon of the divinepagan family of the Vanir in connection with the origins of boat burial(Crumlin-Pedersen 1991a; Crumlin-Pedersen 1995; see Ingstad 1995:253f on the association with Freya in the Oseberg find). Another interpretation referred to is my own concept above of liminal agent , the boat passing the two elements of sea and land and acquiring particular magic strength from this transition (Westerdahl 2005: 8f; 2008:21f), which in fact is done often during the life-time of a boat (Larsson2007: e.g. 297f).The portages, on the other hand, appear to have been transit places inmore than one sense (figure 13). They could, for example, be characteri-zed generally as monuments in the landscape – landscape portals (at leastsome), transit points in transport zones, meeting places, nodes of powerand control of transportation, catalysts of the adaptation of transport vessel types and sizes and techniques and finally as watersheds (borders) of the cognitive world of mobile Man (Westerdahl 2006a).

Figure 13. The portage of Listeid in Vest-Agder, Southern Norway. By way of this important passage the exposed seaboard of the dangerously shallow peninsula of Lista can be avoided.The protected course from the west can be followed to the other important portage of Spange- reid in the same fylke. Photo: the author 2004.

If a portage or watershed is used as a metaphor it could allude to any of these aspects. Probably the territorial and topographical border is still a natural association, even though the current line may run along or transverse to the run of transport.In the age of established kings during the latter part of the Viking Age,it seems plausible that the ship, as a means of power, has been given placein stories on making borders. In earlier contexts personal allegiance wouldbe more interesting than territorial boundaries. The ships of the Viking Age carried sails for the first time in the North and they are contemporary with the rise of kingship in the whole of Scandinavia. Thus, sailing fleetsappear to be more associated with kings than any former chieftainship(Westerdahl 1995: 45f). These ideas apply well to our stories that is of the Orkneyinga saga as well as the two stories of the Kintyre Tarbert.

Preserving the Past, Recording the Present, Informing the Future

Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan Int Society

carruthersclan1@gmail.com carrothersclan@gmail.com

Christer Westerdahl

Reviewed by Tammy Wise CHS- Indiana USA

CLAN SEANACHAIDHI

CLAN CARRUTHERS INT SOCIETY CCIS HISTORIAN AND GENEALOGIST

You can find us on facebook at :

https://www.facebook.com/carrutherscarrothers.pat.9

https://www.facebook.com/CarruthersClan/

https://www.facebook.com/CarruthersClanLLC

Disclaimer Ancient and Honorable Carruthers Clan International Society

I

Until 1936 not much was known about Viking tools. Occasionally, a tool or two would show up on a burial site. In 1936 a farmer found a chest with a chain around it. Inside the chest was a variety of tools that dated back to the Viking Age, they are known as the Mästermyr tools. There are at least five ways in which we know about Viking woodworking. Two pieces of evidence comes from literature and forms of art. The third bit of evidence comes from examining detail in the wood. The fourth bit of evidence comes from modern day tools, Viking tools and their purposes are similar to those of modern tools. The last piece of evidence comes from archaeological discoveries. The list of tools below is what was discovered at Mästermyr, except for the planes and pole lathe. How we know about the use of these tools will be mentioned next to the name and description below.

Until 1936 not much was known about Viking tools. Occasionally, a tool or two would show up on a burial site. In 1936 a farmer found a chest with a chain around it. Inside the chest was a variety of tools that dated back to the Viking Age, they are known as the Mästermyr tools. There are at least five ways in which we know about Viking woodworking. Two pieces of evidence comes from literature and forms of art. The third bit of evidence comes from examining detail in the wood. The fourth bit of evidence comes from modern day tools, Viking tools and their purposes are similar to those of modern tools. The last piece of evidence comes from archaeological discoveries. The list of tools below is what was discovered at Mästermyr, except for the planes and pole lathe. How we know about the use of these tools will be mentioned next to the name and description below.