KING ROLLO THE VIKING

CARRUTHERS ANCESTOR

Robert I Rollo “The Viking” Prince of Norway & Duke of Normandy “Count of Rouen” Ragnvaldsson

BIRTH 14 OCT 846 • Maer, Jutland, Nord-Trondelag, Norway

DEATH 17 DEC 932 • Rouen, Seine, Maritime, Haute-Normandy, France

Married:

Poppa Lady Duchess of Normany De Senlis De Valois De Rennes De Bayeux

872–930

BIRTH 872 • Bayeux, Calvados, Basse-Normandie, France

DEATH 930 • Rouen, Seine-Maritime, Haute-Normandie, France

Rollo as a Warrior

History has many cunning passages”. – T. S. Eliot

“History . . . the portrayal of crimes and misfortunes.” – Voltaire.

The Normans have evoked great interest from the Middle Ages to the present. Vikings who settled in Normandy, were later called Normans. A phrase, A furore normannorum, libera nos, domine (From the violence of the men from the north, O Lord, deliver us), sums up how historians of the early middle ages looked on the Vikings, for they threatened the progress of western civilization for quite some time (Logan 2003, 15).

The Normans have evoked great interest from the Middle Ages to the present. Vikings who settled in Normandy, were later called Normans. A phrase, A furore normannorum, libera nos, domine (From the violence of the men from the north, O Lord, deliver us), sums up how historians of the early middle ages looked on the Vikings, for they threatened the progress of western civilization for quite some time (Logan 2003, 15).

The founder of Normandy, Rollo, was the chief of a small band of ravaging Vikings. He once had a dream where he seemed to behold himself placed on a mountain far higher than the highest, in a Frankish dwelling. And on the summit of this mountain he saw a spring of sweet-smelling water flowing, and himself washing in it, and by it made whole from the contagion of leprosy . . . and finally, while he was still staying on top of that mountain, he saw about the base of it many thousands of birds of different kinds and various colours, but with red wings extending in such numbers and so far and so wide that he could not catch sight of where they ended, however hard he looked. And they went one after the other in harmonious incoming flights and sought the spring on the mountain, and washed themselves, swimming together as they do when rain is coming; and when they had all been anointed by this miraculous dipping, they all ate together in a suitable place, without being separated into genera or species, and without any disagreement or dispute, as if they were friends sharing food. And they carried off twigs and worked rapidly to build nests; and willing[ly] yielded to his command in the vision. (From Hicks, 2016, Introduction).

In Dudo of Saint-Quentin’s History of the Normans, Rollo took heed of the omens in the dream and founded a territory that became the duchy of Normandy, uniting various groups under his lead. Later chroniclers recounted how Rollo’s descendants and those of his followers conquered and ruled kingdoms in England and Sicily and Antioch and further, and led armies on crusade. (Ibid.)

Norwegian-Icelandic sources too tell of a large Viking called Rolv Ganger (Rolv Walker), aka Rollo (English) or Rollon (French). Outlawed in Viking Norway for raiding where he was not allowed to by King Harld Fairhair, Rollo was banished from Norway. He was too big for small horses to carry him, a saga tells. Viking horses may have been quite small.

Rolv and his soldiers secured a permanent foothold on Frankish soil in the valley of the lower Seine, and Rolv became the first ruler of Normandy, France, after King Charles the Simple ceded lands to Rollo and his folks in a charter of 918. In exchange, Rollo agreed to end his brigandage and protect the Franks against future Viking raids along the Seine and around it. He also converted to Christianity in 912, and probably died between 928 and 932. Rollo’s descendants were dukes of Normandy until 1202, and his granson’s grandson’s son Guillaume (dead 1087) conquered England in 1066 (William the Conqueror). (Claus Krag, SNL/Norsk biografisk leksikon, “Rollo Gange-Rolv Ragnvaldsson”.

Two more grants followed; one in 924 and one in 933 – land between the Epte and the sea and parts of Brittany. Relatives of Rollo and his men as well as other Northmen followed, for the pastures were green and lush, there was fish in the sea and rivers, and the climate better than in the North. The formerly raided Normandy became protected and became the best part of France for centuries. Normans also took over England and Wales after a descendant of Rollo, known as William the Conqueror, took over England in 1066 fra 1066 and became king of England. Normans also conquered the southern, richest half of Italy, including Sicily, and several other areas bordering on the Mediterranean Sea. (WP, “Rollo”)

Rollo reigned over the duchy of Normandy until at least 928. He was succeeded by his son, William Longsword. The offspring of Rollo and his followers became known as Normans, “North-men”, men from the North.

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066 and their conquest of southern Italy and Sicily over the following two centuries, their descendants came to rule Norman England (the House of Normandy), the Kingdom of Sicily (the Kings of Sicily) as well as the Principality of Antioch from the 10th to 12th century. To enlarge on that: Bohemond I (ca. 1054–1111) of the Norman Hauteville family was the Prince of Taranto from 1089 to 1111 and the Prince of Antioch from 1098 to 1111. He was a leader of the First Crusade. The Norman monarchy he founded in Antioch outlasted those of England and of Sicily. (WP, “Bohemond I of Antioch”)

Two spouses are reported for Rollo:

(1) Poppa, said by chronicler Dudo of Saint-Quentin to have been a daughter of Count Berenger, captured during a raid at Bayeux. She was his concubine or wife. They had children: (a) William Longsword, born “overseas” (b) Gerloc, wife of William III, Duke of Aquitaine; Dudo fails to identify her mother, but the later chronicler William of Jumieges makes this explicit. (c) (perhaps) Kadlin, said by Ari the Historian to have been daughter of Ganger Hrolf, traditionally identified with Rollo. She married a Scottish King called Bjolan, and had at least a daughter called Midbjorg. She was taken captive by and married Helgi Ottarson.

(2) (traditionally) Gisela of France (d. 919), the daughter of Charles III of France – according to the Norman chronicler Dudo of St. Quentin. However, this marriage and Gisela herself are unknown to Frankish sources. Some details can be hard to verify.

ROLLO RULED WITH A VIKING CODE OF LAW BASED UPON THE CONCEPT OF PERSONAL HONOR & INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY.

Was Rollo Other than Norwegian?

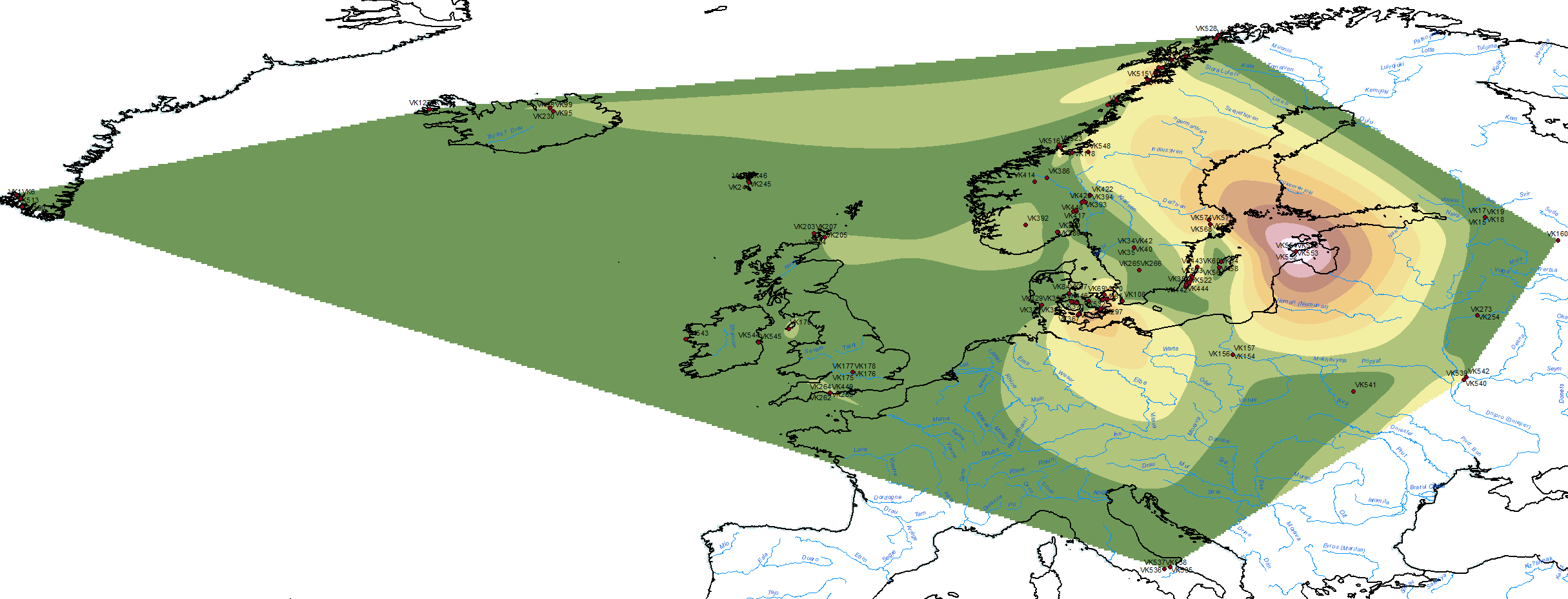

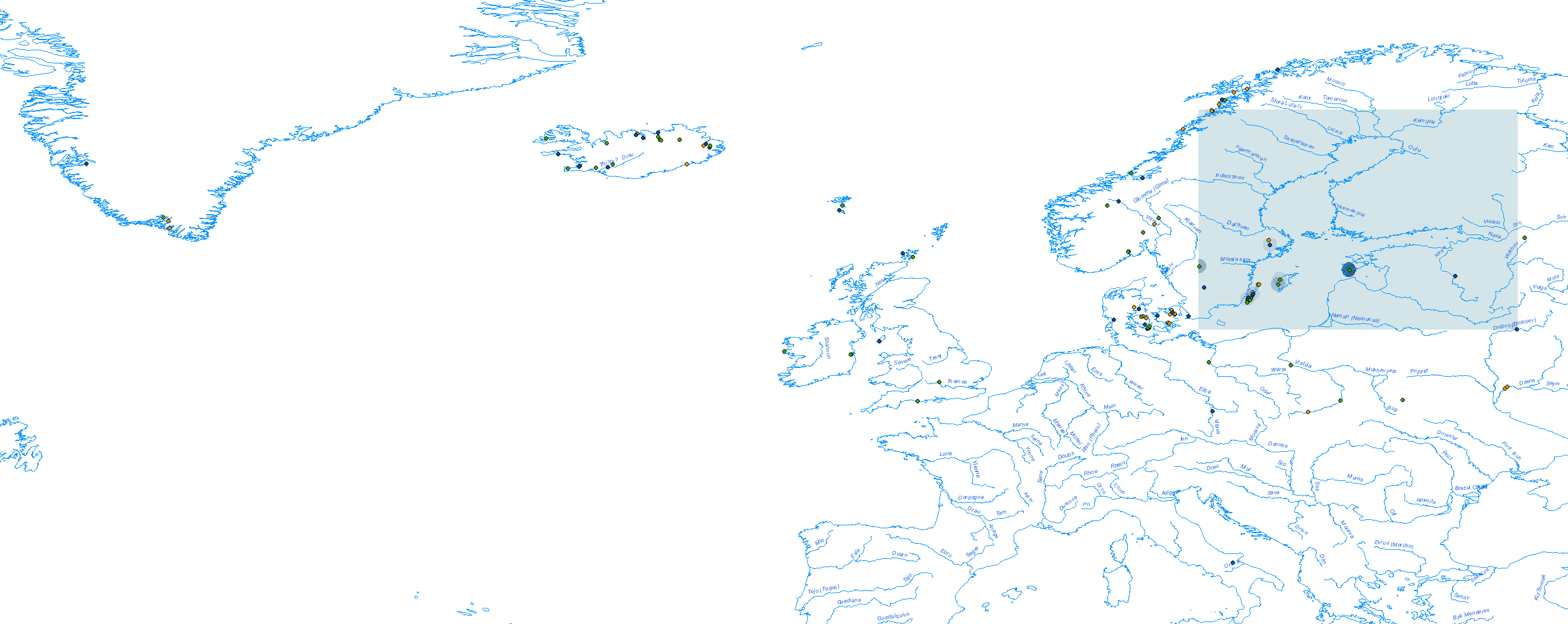

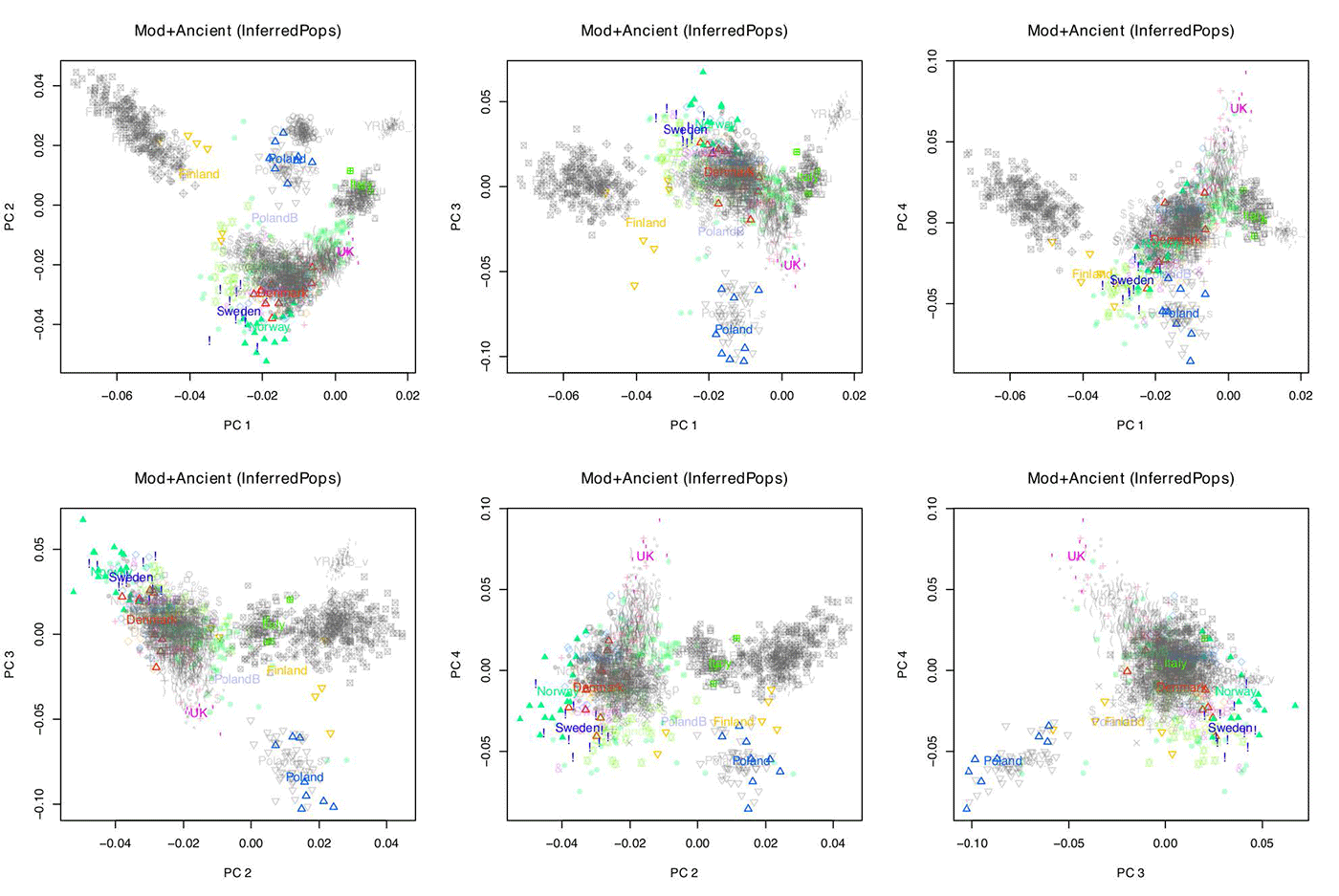

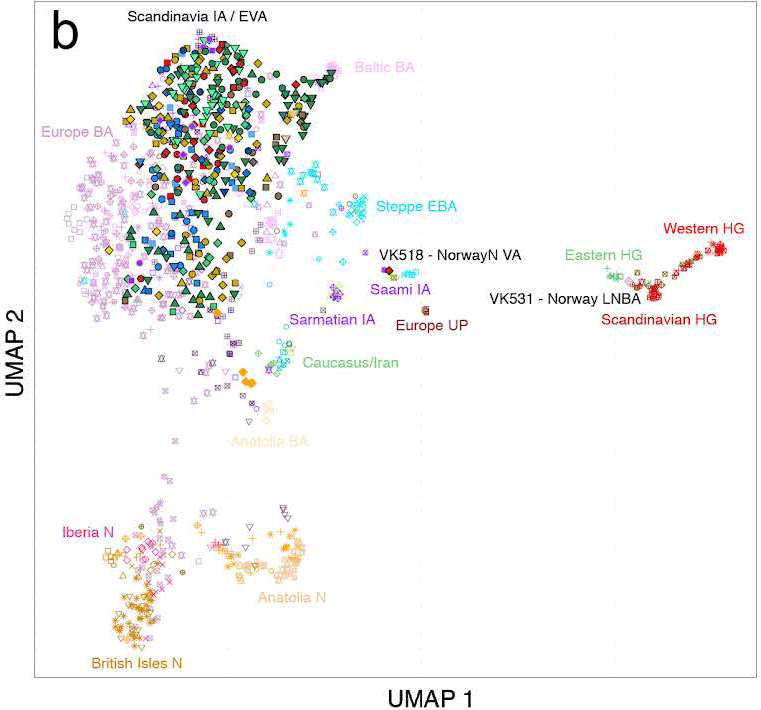

The Rollo story is largely historical – and that he and his men were Northmen is taken to men they were of Scandinavian origin. Norwegian-Icelandic sources have it that Rollo was Hrolf from Norway, one of the Viking raiders.

- The oldest evidence is in the Latin Historia Norvegiae (ca. 1180). It was written in Norway. A quotation from it follows right below the array of Norse sources.

- Fagrskinna‘s chapter 74 tells of William and his ancestor Rolf Ganger (Rollo). This work was written around 1220, estimatedly, and was an immediate source for the Heimskringla of Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla. Fagrskinna contains a vernacular history of Norway from the ninth to the twelfth centuries, and includes skaldic verses that in part have been preserved nowhere else. It has a heavy emphasis on battles. The book may have been written in Norway, either by an Icelander or a Norwegian. (Cf. Finlay 2004)

- In the early 1200s, the Icelander Snorri Sturluson writes about this Hrolf, in Heimskringla, Book 3, section 24; Book 7, section 19, There are stories about the arsonist father and the brothers of Rolf Ganger, at one time rulers of the Orkneys and Moere in Norway. Their tales start somewhere during the reign of King Harald Fairhair (Chaps. 27, 30-32) and say it was he who settled in Normandy. Snorri also tells that Rolv Ganger – also known as Rollo – became one ancestor of the British royal house.

- Other Icelandic sagas from medieval times tell of Hrolf too, as the Orkneyingers’ Saga, section 4.

- From the Icelandic ◦Landnama Book (Ellwood 1898): “Rögnvald, Earl of Mæri, son of Eystein Glumra, the son of Ivar, an Earl of the Upplendings, the son of Halfdan the Old, had for wife Ragnhild, the daughter of Hrolf the Beaked; their son was Ivar, who fell in the Hebrides, fighting with King Harald Fairhair. Another son was Gaungu-Hrolf who conquered Normandy; from him are descended the Earls of Rouen and the Kings of England.” (Part 4, ch. 7)

From Historia Norvegiae, the oldest of the Norse works where Rollo is mentioned:

When Haraldr hárfagri ruled in Norway some vikings of the kin of a very mighty prince, Rognvaldr, crossed the Sólund Sea with a large fleet, drove the Papar [monks and the picts, called Peti here] from their long-established homes [the Orkney Islands], destroyed them utterly and subdued the islands under their own rule. With winter bases thus provided, they sallied forth all the more securely in summer and imposed their harsh sway now on the English, now on the Scots, and sometimes on the Irish, so that Northumbria in England, Caithness in Scotland, Dublin and other coastal towns in Ireland were brought under their rule. In this company was a certain Hrólfr, called Gongu-Hrólfr by his comrades because he always travelled on foot, his immense size making it impossible for him to ride. With a few men and by means of a marvellous stratagem he took Rouen, a city in Normandy. He came into a river with fifteen ships, where each crew member dug his part of a trench which was then covered by thin turves, simulating the appearance of firm ground. They then arrayed themselves on the landward side of the trenched ground and advanced prepared for battle. When the townsmen saw this, they met the enemy in head-on attack, but these feigned flight as if racing back to their ships. The mounted men, pursuing them faster than the rest, all fell in heaps into the hidden trenches, their armoured horses with them, where the Norwegians slaughtered them with deadly hand. So, with the flight of the townsmen, they freely entered the city and along with it gained the whole region, which has taken its name of Normandy from them. Having obtained rule over the realm, this same Hrólfr married the widow of the dead count, by whom he had William, called Longspear, the father of Richard, who also had a son with the same name as himself. The younger Richard was the father of William the Bastard, who conquered the English. He was the father of William Rufus and his brother Henry . . . When established as count of Normandy Hrólfr invaded the Frisians with a hostile force and won the victory, but soon afterwards he was treacherously killed in Holland by his stepson. (Phelpstead 2008, 8-9)

Dr Claus Krag (born 1943) is a Norwegian specialist in medieval Norwegian history, and at present (2018) professor emeritus at Telemark University College. Krag maintains that what Dudo writes of Rollo – Dudo tells he was a Viking from an alpine Dacia – is “totally unreliable”, and that Dudo’s historic and geographic information “is by no means right”. Dr Krag also notes that in French works younger than Dudo’s book, Rollo is presented as a Norwegian.

Based on the much unclear Dudo about an alps-surrounded “Dacia”, some Danes say Rollo was Danish. However, Denmark is flat. Attempts to settle the question by analysis of DNA profiles of likely Rollo descendants have failed so far. [◦”Skeletal shock for Norwegian researchers at Viking hunting”]

Folk Stories Around Rollo

Several Scandinavian folktales front similar basic “success recipes” as those of battling tribes in search of new areas – Saxons, Angles, Danes and other Vikings. It suggests that many folktale heroes walk in shoes quite like those of Rollo by degrees and through much similar stages where success often depends on combat and getting valuables. Those were the times.

In the course of centuries, stories and myths may grow for such as glorifying ends. Norman bards developed romances that venerated kings. However, having a king is not a great good, according to 1 Samuel 8; 10 in the Old Testament: the king is portrayed as a stealing enemy on top. Taxes continue a tradition . . . Also, immodest royalty may breed dependence and un-normal subservience with or without near-symbiotic and half-neurotic servility.

In 1 Samuel 8:11-18 we read how bad a Jewish king will be:

This is what the king who will reign over you will claim as his rights: He will take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses, and they will run in front of his chariots. Some he will assign to be commanders of thousands and commanders of fifties, and others to plow his ground and reap his harvest, and still others to make weapons of war and equipment for his chariots. He will take your daughters to be perfumers and cooks and bakers. He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive groves and give them to his attendants. He will take a tenth of your grain and of your vintage and give it to his officials and attendants. Your male and female servants and the best of your cattle and donkeys he will take for his own use. He will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves. When that day comes, you will cry out for relief from the king you have chosen, but the Lord will not answer you in that day.

But the people refused to listen to Samuel. “No!” they said. “We want a king over us.” [Highlighting added]

Rollo In Normandie

The historian Reginald Allen Brown (1924–89) has written extensively about Normans and the Norman conquest. He is rendered in the following:

“Normandy was created by the three consecutive grants of 911, 924 and 933″. (Brown 1985, 15) Normandy was massively colonised by Scandinavians. Rollo and his successors, as rulers of Normandy, obtained the title of count and valuable rights from before, along with widespread domains. (Cf. Brown 1985, 17-18)

Their buildings seem to document remarkable strength or solidity. The churches were much like bastions. But the duke of Rouen controlled the whole church and his bishops owed him military service for their lands – (Brown 1985, 26)

“From (their) Scandinavian inheritance the Normans derived their sea-faring, much of their trade and commercial prosperity which they shared with the Nordic world, their love of adventure, their wanderlust which led to the great period of Norman emigration in the eleventh century, their dynamic energy, and above all perhaps, their powers of assimilation, of adoption and adaptation.” (Brown 1985,18-19.)

(In AD 911) Charles the Simple, king of the west Franks, granted to a band of Vikings, operating in the Seine valley under Rollo their leader, territory corresponding to Upper or Easter Normandy. To this was subsequently added by two further grants, first the district of Bayeux, and the districts of Exmes and Seez in 924, and second the districts of Coutances and Avranches in 933 in the time of William Longsword, son and successor of Rollo. (Brown 1985, 15) (2)

And from the French Histoire de la Normandie (1862) we find, in the fourth chapter, how Rollo, son of the Norwegian Rognevald, was made an outlaw by the Norwegian king Harald Harfager. He arrived at Rouen with his companions. The inhabitants spontaneously submitted to the him and his men. King Charles at first wanted to fight the Viking, but dropped it. Instead they bargained – Rollo won, he got land and permanent welcome. (Barthelemy 1862, 80 ff)

Rollo of Normandy Statue

Brown puts the matter into relief: “Normans were pagans when they came (and they continued to come long after 911).” (Brown 1985, 24). But their leader, the Viking Rollo, agreed to getting ◦baptised, and many others followed. “The Seine Vikings became Christian Normans, the poachers turned gamekeepers. Revival, characteristically in this monastic age, came first to the monasteries. Jumieges was restored by William Longsword (927–43), son of Rollo, who is said to have wanted to become a monk there himself.” (Brown 1985, 21)

In short time the Normans got the back-up of their astute castles and strongholds, helped themselves to most of it – often they were served by ditches and stockades too. (Brown 1985, 37, 37n)

[It is thought that Rollo showed exceptional skills in navigation, warfare, leadership, and administration. He abdicated to his son Guillame (William) and died in a monastery in 933. Among his people he was for hundreds of years the personification of justice and good government under law. Others, who thought differently, found him cruel and arrogant.]

His son Guillame Longue-Epee (William Longsword) succeeded him. The third duke was Richard sans Peur (the Fearless), and there were many intrigues and hard fights. This Richard died and was succeeded by Richard 2 who massacred Saxons in England at war. The French king Robert became the ally of Richard 2. After his death, Richard 3 succeeded him and died prematurely. Robert le Diable succeeded him and, before he died in Terre-Sainte, became the father of Guillame le Conquerant: William the Conqueror. (Barthelemy 1862, 80 ff)

We find the family tree of William the Conqueror in the book of the historian R. Allen Brown. It looks like this:

- Richard 1 (ruled: 942–96)

- Richard 2 the Good (ruled: 996-1026)

- Richard 3 (ruled: 1026–27)

- Robert 1 the Magnificent /le Diable (ruled: 1027–35)

- William the Bastard / the Conqueror (ruled: 1035–87).

Rollo’s great-granddaughter, Emma married two kings of England, Æhelred the Unready and Knut who was also king of Norway and Denmark. Her son, Edward the Confessor, from the first marriage, was King of England from 1042 to 1066.

A few more dukes of Normandy may be added for the sake of survey of that dynasty line that ruled over Normandy and its English (British) domain:

- Robert 2 (ruled from 1087)

- Henry 1 (ruled from 1106, King of the English (1100-35)

- Henry II, 1135, King of the English (1135-)

“The origins of Normandy in the first decades of the tenth century also reveal the double inheritance of the Normans, from the Scandinavian world from whence they came and from the ancient province of Roman, Frankish and Carolingian Gaul which now they colonised.” (Brown 1985, 17)

“[I]n Normandy by the mid-eleventh century . . . they had adopted Frankish religion and law, Frankish social customs, political organisation and warfare, the new monasticism.” (Brown 1985, 19)

“The Norman monasteries were, by and large, distinguished . . . new . . . vibrant with . . . careless rapture of spiritual endeavour”. The (Normans) became great spirituals – intensely aristocratic. (Brown 1985, 23)

Normans restored and built on monasticism and left robust architectural monuments. Some are still there, more or less intact. The Tower of London was started by Normans, for example. King William had much of it built. “The tower at Rouen was built by Richard 1 (943Rw11;96) and is glimpsed from time to time in the reign of his successor and thereafter . . .. It may have been the prototype for the great Norman towers at Colchester and London. (Brown 1969, 37, 37n) (4)

Normans went on and built monastic churches at such places as Jumieges and many other places. “They added their cathedrals at Rouen, Bayeux [etc.] Many of these major works of Norman Romanesque architecture survive in whole or part”. (Brown 1985, 26)

“Some Normans (including Norman clergy) were patrons of the arts and scholarship . . . and almost all of them were mighty builders.” (Brown 1985, 25)

The French Version

Statue of Rollo of Normandy, Falaise

In 820 peasants . . .along the Seine saw in the distance ten or so curious war ships called—Drakkar because of the animal sculpted into the prow or the stern, which was actually a dragon—the men from the North didn’t travel with their women as they could easily find them on the spot!

Swearing by the names of Thor and Odin—Vikings plundered, pillaged, raped and slaughtered up until 911 when the famous treaty of Saint Clair sur Epte was signed between the Frank king Charles the Simple and Rollon or Rolf, chief of the men from the North.

On the whole our invaders calmed down, adopting a somewhat bourgeois attitude to life in this beautiful region which was to become Normandy.

Soon it was the time for William the Conqueror who, on October 14th, 1066 won the battle of Hastings along with a kingdom—William’s heirs were known as the Plantagenets, and they reigned over Normandy and England. In 1189, Richard the Lionheart divided the double crown.

Rollo and Dudo

Rollo was the son of Earl Ragnvald of More, Norse sagas tell. Two of his brothers were Ivar and Tore. Three more were Hallad, Einar and Rollaug. Hallad and Einar in due time became earls of the Orkneys, each in his turn. [eg, Harald Fairhair’s Saga]

After being made an outcast by the tyrant king Harald Harfager, Rolf voyaged to the western isles. Obviously he could count on support from relatives. The earl of the Orkneys was his paternal uncle, succeeded by that uncle’s son, that is, Rollo’s cousin, and later again by his own brothers Hallad and Einar.

The old sources hold that Rolv took his residence in certain tracts of what today is the domain of Scotland. The Landnamaboka mentions Rolv got a daughter, Kathleen:

Helgi . . . harried Scotland, and took thence captives, Midbjorg, the daughter of Bjolan the King, and Kadlin, the daughter of Gaungu Hrolf or Rolf the Ganger; he married her. (Part 2, ch. 11).

Before Helgi had harried and married, Rolv of the Sagas had travelled from Scotland and the isles near it, to Valland, near the English Channel. The Vikings’ Valland consisted of the southern Netherlands, Belgium and parts of Normandy, roughly said. He took over Normandy in three steps. The Sagas identify him with the Rollo that the Frank king Charles the Simple bestowed it on.

Rollo in Alesund, Norway

Rolv Ganger converted and settled in Rouen. Next he granted many of his Viking companions ample landed property. It was feasible to go north and fetch one’s women and children and kin to the new land, for the soil was fit, there was much fish, and as members of the ruling class they were much safer or freer than those who submitted to the tyranny of Harald Fairhair and his family in Norway and its colonies in several western islands (cf. Simonnaes 1994, 43).

Normans built fortresses on strategic places, and many rustic castles were to come along with them in a short time. All able men had to serve in the Norman military forces. The formerly ruined, marauded region was turned into one of the foremost in France, and Rouen became the second largest city in France, while Hrolf became the originator of the Norman duchy. [Simonnaes 1994 39, 45-46]

Dudos’ Work

Dudo was a visiting French scholar who wrote in verse and prose about the first three rulers of Normandy and their origins. His poetry is different from that of skalds, the Norse bards. It is not complex, as theirs, and he does not glorify war so much either. He is moralistic like earlier Christian eulogists and writers of biographies of saints (Christiansen 1998, xviii). “It was hagiography that moulded his work,” Eric Christiansen aptly sums up (ibid, xxi), and, “there is no sign that Old Norse poetry was ever composed or appreciated in Normandy (1998, xvii; cf. Ross 2005).”

Dudo’s eulogising chronicle (ibid. xxv) is about one family’s rise from defeat and exile in the world of Vikings to an honoured place among the great territorial rulers of France. Dudo recounts two campaigns in England by the founder, Rollo, and a series of stirring events otherwise, including the murder of Rollo’s son William, and the kidnapping, escape and precarious early career of Dudo’s first patron, Count Richard I.

Historians on the whole have doubted much in Dudo’s book, for its historical details are inaccurate. Yet it it is virtually the only source for very early Norman history. Recently, some scholars maintain that Dudo had better be seen as a propagandist.

Dudo’s work has the nature of a romance, and has been regarded as untrustworthy on this ground by such critics as Ernst Dümmler and Georg Waitz. Further, Leah Shopkow has more recently argued that Carolingian writing, particularly two saints’ lives, the ninth-century Vita S. Germani by Heiric of Auxerre and the early tenth-century Vita S. Lamberti by Stephen of Liége, provided models for Dudo’s work. (WP, “Dudo of Saint-Quentin”)

Rollo Grave at the Cathederal of Rouen

New editions of central Norman chronicles have surfaced over the last thirty years. The History of the Normans in Eric Christiansen’s English translation (1998) is said to be “fairly true to Dudo’s often pompous, bloated style” while at the same time being readable, and accompanied by copious, explanatory notes. Christiansen recognises that Dudo is unreliable as a historical source, and he acknowledges the Scandinavian side of the early Normans. Histories of Normans have a potentially broad appeal. On the Internet there has been a version edited by Felice Lifshitz (1996).

Dudo’s content: A few observations

O thou the magnanimous, pious, and moderate!

O thou the extraordinary God-fearing man!

O thou the mangificent, upright and kindly!

O thou miraculous, goodly just man!

O thou peace-maker and offspring of God!

O thou the munificent, holy and moderate!

O thou the incarnadine merciful Richard!

O thou the the long-suffering, Richard the prudent!

O thou most famous one, Richard the comely!

O thou justiciar, Richard the mild!

– All manner of nations duly declare.

Mild one, remember what you see in the book,

Nourish your heart and your soul on these things

That you may be joined to the matter you read.

– Verses to Richard, son of the great Richard (in Christiansen 1998, 8)

A clergy view shines through.

The commisioned chronicler of the Norman dukes, Dudo, tells in Latin (ca. 1015–20) that Rollo was the son of an uncertain king in “Dacia”. ◦Gesta Normannorum:

Spread over the plentiful space from the Danube to the neighborhood of the Scythian Black Sea, do there inhabit fierce and barbarous nations, which are said to have burst forth in manifold variety like a swarm of bees from a honeycomb or a sword from a sheath, as is the barbarian custom, from the island of Scania, surrounded in different directions by the ocean. For indeed there is there a tract for the very many people of Alania, and the extremely well-supplied region of Dacia, and the very extensive passage of Greece. Dacia is the middle-most of these. Protected by very high alps in the manner of a crown and after the fashion of a city. – [From chapter 2, second paragraph in Gesta Normannorum by the chronicler Dudo ca. 1015]

Extracts from Dudo of St. Quintin’s

One thing that stand out from Dudo’s obscure and glorifying marvel is this: If what is called Dacia is surrounded by very high alps, it isn’t Denmark. His Dacia stands out as some very fertile, southern Alp tract (Balcanlike). (Steenstrup 1876, 30, 31)

Against a claim by the Danish Johannes Steenstrup in 1876, there is not one mention of Rollo in classical Danish sources. DNA analyses of Norman descendants of Rollo could have helped in finding out about his origin, but so far no fit DNA has been detected.

The Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus from about 1200, has no mention of any Danish Rollo in ◦The Danish History.

In Normandy, Rollo is celebrated as a real Viking from More on the west coast of Norway [Cf. Simonnaes 1994 35]

Rollo in Fargo, North Dakota

In 1911, during the Norman Millennium celebrations, the city of Rouen in Normandy decided to create two copies of its Rollo statue. One replica was sent as a gift to Ålesund, Norway. The earls of Moere were headquartered somewhere nearby Ålesund, it is suggested.

The other replica went to Fargo in North Dakota. The two bronze statues were copied from an original stone statue sculpted in 1863 by Arsene Letellier, erected in Rouen in 1865.

In Fargo, the dedication ceremony in 1912 included a speaker from the French embassy in Washington. A proclamation by the mayor of Rouen, bound in leather with gold seal of the city, gold leaf and other ornamentation, read in part,

“Since these ancient times, these fierce warriors have populated and have become a hard-working people whose importance is shown by the powerful association of the Sons of Norway which has preserved the cult of memory, and which participated last year in the celebrations in the ancient Duchy of Normandy.”

The celebrations were concluded with a parade down Broadway. The Rollo statue was relocated in the 1980s and now stands in a little park. [Simonnaes 1994 39, 48, 40]

CLAN CARRUTHERS SINCE 1983

Preserving Our Past, Recording Our Present, Informing Our Future

Ancient and Honorable Clan Carruthers Int Society CCIS LLc

carruthersclan1@gmail.com carrothersclan@gmail.com

CLAN CARRUTHERS INT SOCIETY CCIS HISTORIAN AND GENEALOGIST

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.

For the Gotland Vikings, accumulation of wealth in the form of silver coins was clearly a priority, but they weren’t interested in just any coins. They were unusually sensitive to the quality of imported silver and appear to have taken steps to gauge its purity. Until the mid-tenth century, almost all the coins found on Gotland came from the Arab world and were around 95 percent pure. According to Stockholm University numismatist Kenneth Jonsson, beginning around 955, these Arab coins were increasingly cut with copper, probably due to reduced silver production. Gotlanders stopped importing them. Near the end of the tenth century, when silver mining in Germany took off, Gotlanders began to trade and import high-quality German coins. Around 1055, coins from Frisia in northern Germany became debased, and Gotlanders halted imports of all German coins. At this juncture, ingots from the East became the island’s primary source of silver.